Wondering why guac is extra extra at Chipotle these days? Afraid your milk consumption habits may not be financially sustainable? You can thank the highest inflation rate in thirty years.

If you think that sounds scary, you’re not alone. People seem to be losing their minds about it. No one likes to pay more for the same.

But while everyone has an opinion about this bout of inflation, almost no one really understands what’s causing it. And that’s critical to understanding a number of things, such as when it will go away, who’s hurting, what the government can do to make it better, and how it will affect President Biden politically.

Today’s post will look at the first two questions—what’s causing it and when it’ll go away. A second post tackles the rest.

A look at the numbers

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, consumer prices in the US were 0.94% higher in October than in September, rising 6.2% over the past year. After a decade of low inflation, this is the fastest 12-month pace since 1990 and the fifth consecutive month with inflation above 5%.

Want to understand the world a little better? Subscribe to GZERO Daily by Ian Bremmer for free and get new posts delivered to your inbox every week.

Part of this story can be explained by energy and food prices, which are up 30% over the last year globally. Despite what you might have heard, these have nothing to do with “Biden shutting down the Keystone XL pipeline” or levying a “Thanksgiving tax.” (Neither of those things exists.)

The truth is that oil and gas prices, which are set in international markets, have been climbing because of increased global demand as the world economy recovers from the pandemic. Fears about gas shortages across Europe and Asia ahead of the winter, combined with a slowdown in Chinese coal burning and OPEC+ oil producers’ refusal to increase supply by enough to meet the demand surge, have all contributed to the energy crunch.

Similarly, prices of food products traded internationally (including vegetable oils, cereals, sugar, meat, and dairy) have soared as high global demand has been met with supply constraints caused by the pandemic, extreme weather events, and political instability.

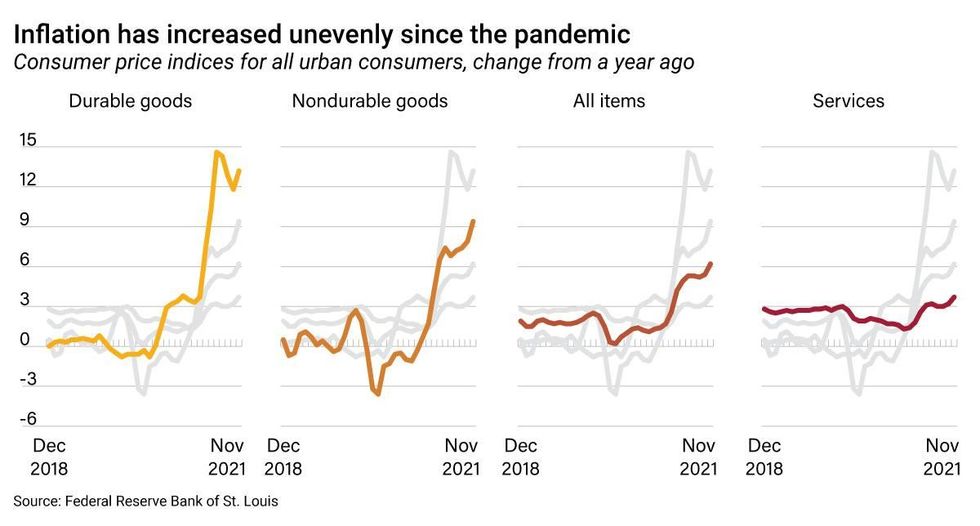

But core US inflation, which excludes energy and food prices, still rose 4.6% over the past year, the fastest pace since 1991. This has been driven by rising prices of goods, especially durable goods like cars, furniture, and appliances, which have increased by over 10%. In comparison, services prices are subdued and played no part in inflation over the last year (although they have been picking up since April on the back of an improving public health situation).

Blame lies with the pandemic, not policy

Conservative pundits have been flooding the airwaves claiming the Biden administration stoked inflation by injecting too much stimulus into the economy, causing there to be “too much money chasing too few goods.” Does that mean that inflation is the result of bad policy?

The data says no.

When the pandemic hit, large parts of the economy were forced to shut down. The virus disrupted every activity that required in-person interaction, including manufacturing operations, services like gyms, restaurants, travel, schools, etc., and jobs that couldn’t be done remotely. Lots of businesses were shuttered, millions lost their jobs.

The US government responded by giving people and businesses a ton of money to pay their bills, avert mass bankruptcies, and prevent another Great Depression. This was smart, and wildly successful. Poverty actually declined, disposable income and household saving increased to record-highs, and asset prices boomed.

Because they couldn’t spend the extra cash on things like haircuts, travel, or restaurants, Americans turned to at-home consumption, ordering everything from gym equipment and office furniture to loungewear and gardening tools. In other words, the government’s necessary and successful response to Covid amid pandemic lockdowns triggered a consumption boom that saw demand for goods rise way above pre-pandemic levels—even though millions of jobs had just been destroyed.

Consumer spending has been uneven since the pandemicFederal Reseve Bank of St. Louis

Consumer spending has been uneven since the pandemicFederal Reseve Bank of St. Louis

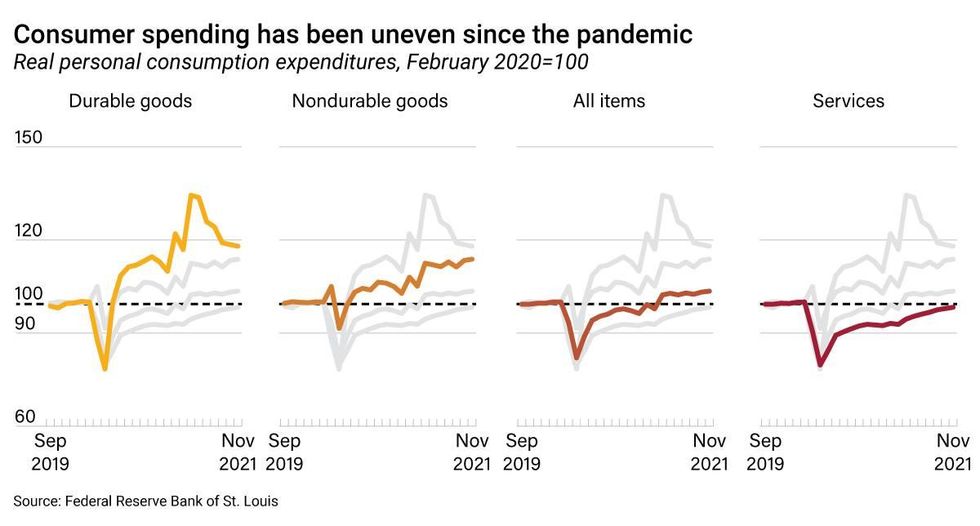

Awash in new orders, global supply couldn’t keep up. Not only had Covid disrupted manufacturing, logistics, and distribution operations, but every link in the chain had braced for a prolonged slump.

Global supply chains are deliberately designed to be lean, prioritizing efficiency over resilience. Usually it works well, but when (for whatever reason) demand exceeds normal supply levels, they have no spare capacity. As a result, rather than increase output and employment, additional spending causes prices to rise.

That’s exactly what happened in the face of what was a historically unprecedented, and wholly unexpected, surge in demand for goods. The mismatch between Americans’ voracious appetite for stuff and the world’s ability to sate it manifested in shortages, soaring costs, and rising prices. The bottlenecks showed up throughout the supply chain, from raw materials and intermediate goods to freight transport and warehousing. Snarls upstream caused shortages downstream, increasing costs and prices along the way.

Will US kids get their toys on time?Institute for Supply Management, Case Statista, GZREO Media

Will US kids get their toys on time?Institute for Supply Management, Case Statista, GZREO Media

When vaccines rolled out and economic activity picked up, labor demand boomed and previously unemployed workers started coming back from the sidelines, boosting demand even further. But not everyone came back. Some workers retired early or left the workforce to care for their children. A few decided to hold out for better opportunities and could now afford to because of the pandemic relief. Most importantly, a record number of predominantly low-wage workers began quitting their jobs en masse, encouraged by the highest-ever job opening rate on record.

The effect of this “Great Resignation” has been a labor shortage, concentrated in low-paying occupations, that is forcing employers to finally compete for workers. In turn, this increase in labor costs has been passed on to consumers in the form of higher prices.

To recap:

- Rising food and energy costs, including gas prices at the pump, are a global phenomenon caused by the pandemic and its global aftereffects.

- The policy response to the pandemic was appropriate and effective at sustaining aggregate spending and preventing a lot of unnecessary suffering. While the economy is doing well, it is by no means overheating, as evidenced by the fact that GDP is still 2.6% below its pre-pandemic trend and employment hasn’t fully recovered.

- Rising prices of goods are a direct result of the pandemic, which shifted the composition of spending away from services and toward goods, destroyed productive capacity, disrupted supply chains, and reallocated labor.

- Inflation is being exacerbated by bottlenecks that were waiting to happen, predating the pandemic but triggered by it. For example, the ground shipping industry had been lowering trucker pay and eroding worker protections for decades. Now there’s a massive trucker shortage preventing goods from moving from ports to warehouses to retailers to your doorstep.

- Taking the pandemic’s effects on consumption patterns and supply chains as well as the latent vulnerabilities in our just-in-time mode of production as given, high inflation was the price to pay to prevent suffering on a scale not seen since the Great Depression. No alternative policy response could’ve gotten the best of both worlds.

Let's see who this really is... |

The story is roughly the same outside the US. Last month, consumer prices jumped 1.1% in Britain and 0.7% in Europe. Even Germany, which unlike the US didn’t respond to the pandemic with large-scale fiscal stimulus, has seen inflation rise to 4.6% over the past year. If this doesn’t convince you that inflation is mainly about the global pandemic rather than US policy choices, I guess nothing will.

When will inflation let up?

The jury is still out on this one.

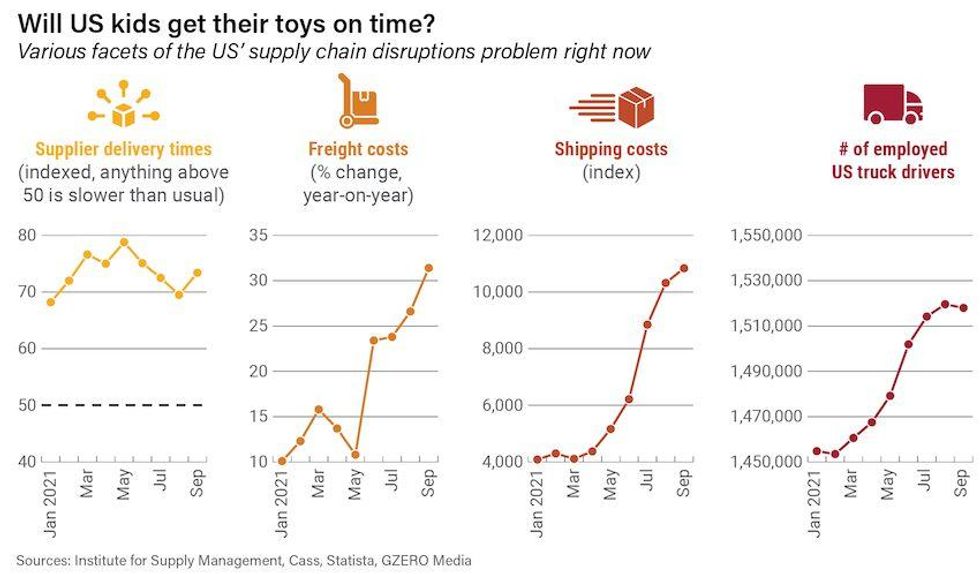

There are a few reasons why inflation could in theory remain elevated for a while. A strong labor market, still-high disposable incomes, and accommodative monetary policy could continue to sustain high demand. The price of services like travel, hospitality, and restaurants will accelerate as booster shots encourage people to go out. Supply chains may take some time to return to normal, given how sticky they have been. The great resignation could persist, making labor scarcer and putting upward pressure on wages. If inflationary expectations set in, workers might demand higher pay to keep up and consumers may start to frontload spending, in turn accelerating wage and price inflation… Again, not implausible.

But there are also compelling reasons to think inflation will come down on its own soon, as the factors that caused it begin to ease. The bulk of the fiscal response to the pandemic is over, so spending levels will return to normal. As the pandemic abates and the economy reopens fully, consumption will swing back toward services and away from goods, workers will return to work, and supply chains will untangle. Once Covid treatments and vaccines are available everywhere, new outbreaks will stop causing supply disruptions and unbalanced demand.

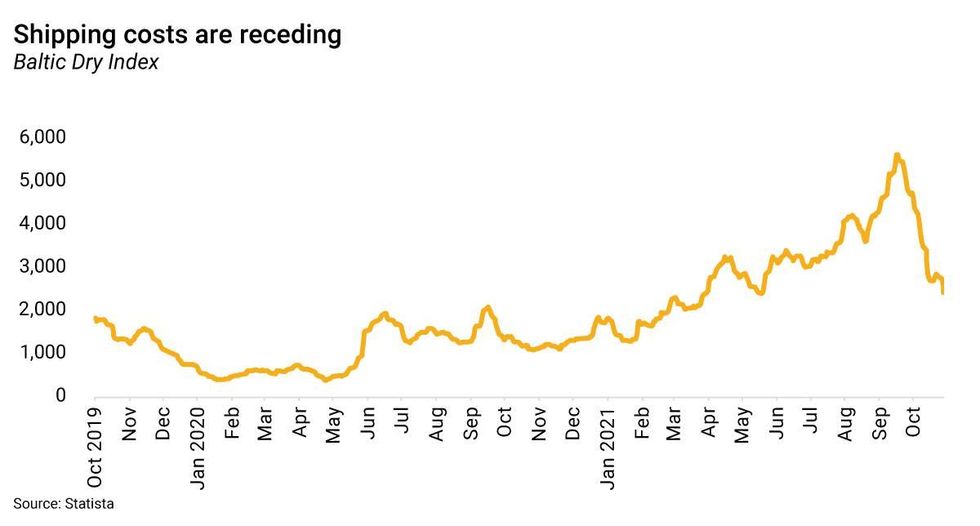

Shipping costs are recedingStatista

Shipping costs are recedingStatista

We are already seeing these dynamics play out in the data. Consumption patterns are shifting back towards services, with durable goods expenditures falling by 8% since April and inventories surging. Bottlenecks are starting to unwind, with the Baltic Dry Index, a measure of global shipping rates, plunging 50% since October. Container traffic at the Port of Los Angeles is down 30%. The International Energy Agency says oil prices are about to peak.

On balance, the evidence suggests inflation will come down gradually over the next year. The trillion-dollar question is what happens in the meantime. Read my next post to find out.

🔔 And if you haven't already, don't forget to subscribe to my free newsletter, GZERO Daily by Ian Bremmer, to get new posts delivered to your inbox.