This November marked the 88th commemoration of the 1932-33 Ukrainian Holodomor, the famine caused by Joseph Stalin’s forced collectivization of agriculture that killed more than 3 million Ukrainians out of between 6 and 11 million total victims across the Soviet Union.

The narrative around the Holodomor has been the subject of controversy for decades. While today historians largely agree that the famine was the result of Soviet policy (rather than a tragic natural disaster) and that ethnic Ukrainians were disproportionately affected by it (they were 30-50% of the victims but only 21% of the Soviet population), this wasn’t always the case.

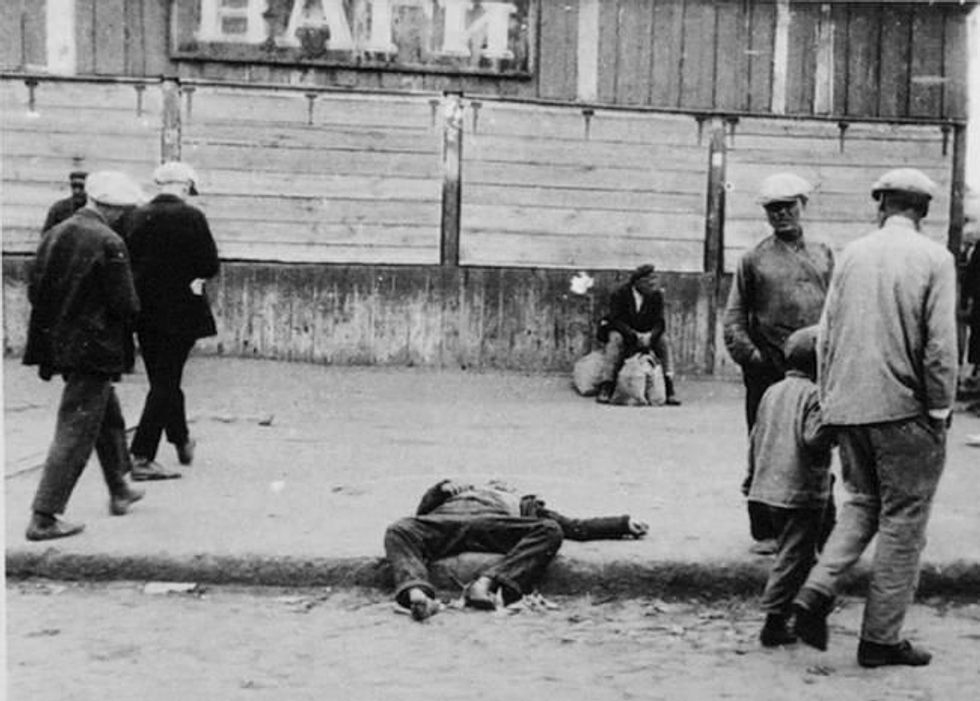

"The sympathy shrinks," the photographer notes in his original caption. Kharkov, Ukraine. 1933.(Wikimedia Commons)

"The sympathy shrinks," the photographer notes in his original caption. Kharkov, Ukraine. 1933.(Wikimedia Commons)

In fact, it wasn’t until my PhD advisor and dear mentor Robert Conquest published his 1987 book, The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine, that these facts gained wide acceptance.

Want to understand the world a little better? Subscribe to GZERO Daily by Ian Bremmer for free and get new posts delivered to your inbox every week.

Conquest’s Harvest of Sorrow was the first book to authoritatively document the Holodomor. It was also the first to credibly claim that the famine was deliberately imposed on the Ukrainian peasantry by the Soviet state for ethnic reasons. The book had such an impact that many Ukrainians first learned about the deadly famine from translated excerpts broadcasted on Radio Liberty. (Incidentally, Bob was the person that got me interested in Ukraine, to the point where I moved to Kiev briefly in 1992 and wrote my dissertation on the politics of ethnicity in Ukraine and Russia.)

But not everyone was convinced. Several scholars rejected Conquest’s conclusion that the famine was systematically biased against Ukrainians and therefore that it was genocide. Instead, they noted the famine killed many non-Ukrainians, both in Ukraine and elsewhere in the Soviet Union. While Stalin’s agricultural policies did kill Ukrainians at a higher rate than other ethnic groups, they claimed this was due to factors outside the government’s control, such as bad weather and pre-famine policies and features (such as Ukrainians being disproportionately represented in agriculture or living on more productive land) rather than deliberate state policy.

Soviet guards take crops from Ukrainian farmers in Odessa, 1932.(Wikimedia Commons)

Soviet guards take crops from Ukrainian farmers in Odessa, 1932.(Wikimedia Commons)

To this day, outside of academia there is no universal consensus about whether the 1932-33 famine was a crime against humanity committed in the Soviet Union’s pursuit of its economic and political objectives or an act of genocide against the Ukrainian people.

The Ukrainian government officially recognized the Holodomor as a genocide in 2006, but only 15 other nations (including Australia, Canada, Mexico, and the Baltics) have followed suit. Russia categorically rejects the label for obvious reasons. Opposition from the Kremlin explains why the UN General Assembly and the European Union, which depends heavily on Moscow for energy and regional stability, recognize Holodomor as a crime against humanity but not a genocide. The potential backlash from Putin also explains why no US president has ratified the genocide declaration issued by the US Congress.

Enter a new study published last July by economists Andrei Markevich, Natalya Naumenko, and Nancy Qian, titled “The Political-Economic Causes of the Soviet Great Famine, 1932–33”. From the abstract (emphasis mine):

This study constructs a large new dataset to investigate whether state policy led to ethnic Ukrainians experiencing higher mortality during the 1932–33 Soviet Great Famine. All else equal, famine (excess) mortality rates were positively associated with ethnic Ukrainian population share across provinces, as well as across districts within provinces. Ukrainian ethnicity, rather than the administrative boundaries of the Ukrainian republic, mattered for famine mortality. These and many additional results provide strong evidence that higher Ukrainian famine mortality was an outcome of policy, and suggestive evidence on the political-economic drivers of repression. A back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests that bias against Ukrainians explains up to 77% of famine deaths in the three republics of Russia, Ukraine and Belarus and up to 92% in Ukraine.

In short, the paper offers novel, rigorous, and compelling evidence that the Holodomor was indeed premeditated and intentional genocide against ethnic Ukrainians, rather than the unintended consequence of bad but ethnically neutral collectivization policies.

A woman walks by two starving peasants dying on the streets of Kharkiv, Ukraine in 1932 (Wikimedia Commons)

A woman walks by two starving peasants dying on the streets of Kharkiv, Ukraine in 1932 (Wikimedia Commons)

The authors find that higher famine mortality for ethnic Ukrainians was not due to “differences in agricultural production, weather or urbanization” or to Ukrainians’ socio-cultural and institutional differences relative to other Soviet ethnic groups. Moreover, ethnic Ukrainians’ excess mortality was just as high in Russia as in territorial Ukraine, meaning that “Soviet policies which led to the famine targeted ethnic Ukrainians rather than Ukraine.” Combined, these findings suggest that ethnic Ukrainians were systematically targeted. This ethnic bias explains 9 out of 10 famine deaths in Ukraine and close to 8 out of 10 deaths throughout the Soviet Union.

But why did the Soviet state target ethnic Ukrainians? Did Stalin want to exterminate them simply because of who they were, or was there a more instrumental reason? The authors test a bunch of hypotheses and rule out crude ethnic hatred as the main driver, finding that “Ukrainian areas do not suffer higher famine mortality if they are not agriculturally productive.” Instead, they conclude that the targeting of Ukrainians stemmed from Stalin’s need to control agricultural production. Famine mortality was driven by collectivization and grain procurement, the regime’s centrally planned agricultural policies, which were “more intensively enforced in regions with larger Ukrainian population shares”:

Since Ukrainians were the largest ethnic group in productive areas, had a stronger ethnic identity than other groups and were in sharp conflict with the Bolsheviks in 1917 and during the Civil war, the regime repressed Ukrainians more than other groups living in productive regions to overcome potentially stronger resistance[…] Amongst the subversive peasants according to Stalin’s view, ethnic Ukrainians were the most problematic […] Thus, it is likely that the Soviets systematically repressed Ukrainians during the famine to strengthen their control over agriculture.

These findings vindicate Conquest’s conclusions: Holodomor was a genocide perpetrated along ethnic lines, the scars of which continue to live on.

Ukrainian activists protest outside the Russian embassy in Kiev in 2020, during a protest called "You killed us then and continue to kill us now".(Sergei Supinsky/AFP via Getty Images)

Ukrainian activists protest outside the Russian embassy in Kiev in 2020, during a protest called "You killed us then and continue to kill us now".(Sergei Supinsky/AFP via Getty Images)

Even if the Holodomor itself wasn’t primarily motivated by Russian hatred of Ukrainians, the famine inflamed ethnic tensions that have sown discord between the two nations ever since the collapse of the Soviet Union. Remember this the next time you read about the West’s worries that Russia might invade Ukraine… again.

🔔 And if you haven't already, don't forget to subscribe to my free newsletter, GZERO Daily by Ian Bremmer, to get new posts delivered to your inbox.