There's never a great time to impose higher taxes on funeral services — but doing it in the middle of a raging pandemic is an especially bad move. Yet that was one of a number of measures that the Colombian government proposed last week in a controversial new tax bill that has provoked the country's largest and most violent protests in decades.

In the days since, the finance minister has resigned, the tax reform has been pulled, and President Iván Duque has called for fresh dialogue with activists, union leaders, and opposition politicians.

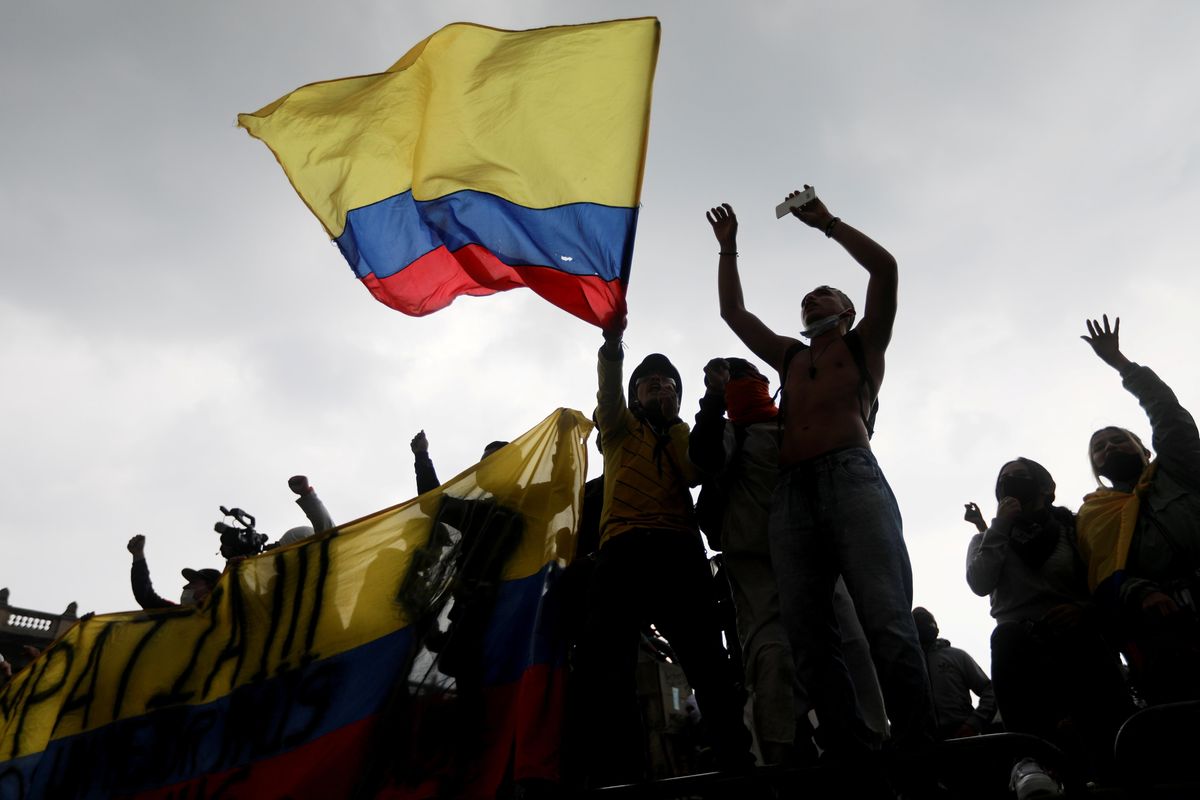

But demonstrations, vandalism, and deadly clashes with police have only intensified. Two dozen people are dead, 40 are missing, and the UN has criticized Colombian police for their heavy-handed response.

How'd we get here? The Colombian government has a common math problem: it spends more money than it raises.

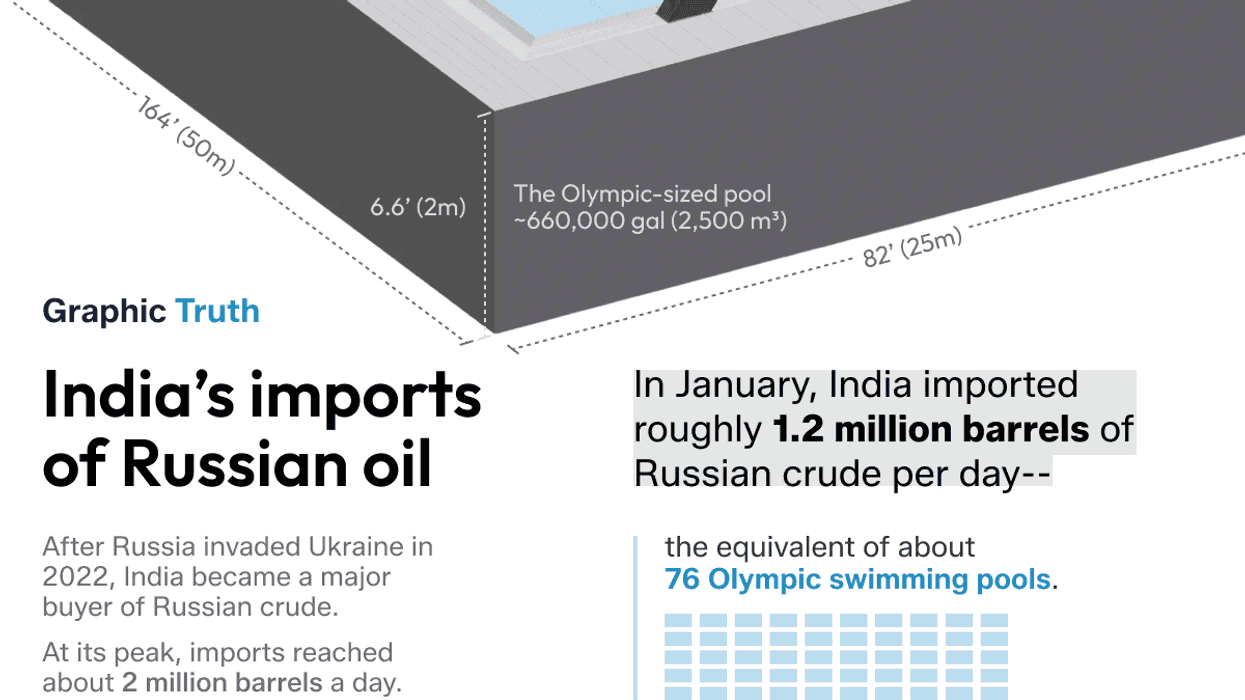

Even before the pandemic, the country's oil exports — a major source of government revenue — were dwindling, and over the past year, the deficit tripled. Now, to pull the country out of its worst economic crisis in decades, it's even more urgent to top up state coffers.

But Colombia has one of the lowest tax hauls of any country in the OECD, and ratings agencies warn that without a tax reform of some kind, a downgrade awaits. That would make it more expensive for Colombia to borrow money abroad, depleting state resources even further.

Duque's proposal would have raised levies on corporations and the rich, while boosting social spending to alleviate poverty. But it also expanded taxes for the middle class and poor, eliminated exemptions for pensions, and added a sales tax to many staple consumer goods and services. Even water would have gotten more expensive. Water!

The math may have been sound but, in a country reeling from the pandemic, the politics were horrific. Over the past year, 3 million more Colombians fell into poverty, raising the poverty rate by 7 points to a staggering 42 percent of the population (source in Spanish.) Thousands of businesses have closed. And the country is now in the throes of a third COVID wave: daily new cases have soared sixfold in the past two months.

Small wonder that when the tax bill was unveiled, three-quarters of Colombians supported a national strike in response.

But these protests are about more than taxes. For several years, a large part of Colombian society has been upset about rising inequality, an epidemic of violence against human rights leaders, rising crime in the cities, and poor healthcare and education.

Just before the COVID crisis started, in late 2019, mass protests over these issues shook Bogotá for days. Today's protests are in part a resurgence of grievances bottled up — and made worse — by the pandemic.

Elections loom. Next year, Colombians will elect a new president. Term limits keep Duque from running again — and with his meager 30 percent approval rating, that's probably just as well. But the social crisis has boosted the fortunes of Senator Gustavo Petro, a leftwing former mayor of Bogotá who got his start in political life as part of the M-19 urban guerrilla movement.

A recent poll showed Petro would get close to 40 percent of the vote if the ballot were held today, an increase of 15 points since last fall (source in Spanish). That a leftwinger should be so popular is a sea change in Colombia, long a center-right country in which decades of war with Marxist-inspired militants — and the recent disaster next door in socialist-led Venezuela — had created a stigma around leftist politics at the national level.

Colombia's crisis is also a broader caution: Many countries are staggering out of the pandemic with weak state finances. The IMF recently found that debt as a percentage of GDP in emerging market economies soared 10 points last year to an average of 65 percent. Meanwhile, poverty and social spending needs have only risen as a result of the economic crisis.

The current upheaval in Colombia is a taste of what could come for many middle-income and poorer countries if they botch the politics of raising revenue.

But no matter how they go about it — not taxing the dead is a smart way to avoid antagonizing the living.