“Those clouds are not real,” the woman standing next me at the car pickup spot said, pointing to the overcast skies above San Diego.

I had just arrived here to speak to a group of business leaders about Eurasia Group’s Top Risk report and the political landscape ahead in a year of polarizing elections.

“Sorry?”

“It’s usually beautiful and sunny here, but now with the cloud seeding, all we get is this,” she explained, adopting that apologetic tone proud locals use when their home isn’t exhibiting its best for a visitor. She interrupted her weather flow to give me some other tips about local restaurants — “check out Roberto’s taco stand” — and hiking in the area, before returning to the weather.

“Yeah, you know all those floods we had this past month?” she asked rhetorically. “They’re from these clouds the climate folks created with their cloud seeding because they want to block out the sun to cool the Earth down.”

And then she added the kicker: “And it’s poison, you know.”

Of all the risks I had come here to talk about, the poison-fake-clouds-causing-floods risk did not make the agenda. But the theory is so pervasive in California that the LA Times just wrote a long story in order to, well, rain on the conspiracy parade.

A quick background might be in order.

Cloud seeding is not new. It’s been around since the late 1940s, when a meteorologist named Vincent Schaefer first tried to stop ice from forming on airplane wings by firing chemicals like silver iodide into the air to stimulate condensation. Since then it’s been happening all over the world to induce rain or reduce hail storms — but it’s not a Harry Potter magic trick that can cause mass flooding. Cloud seeding, at best, can increase precipitation by about 5%-10%, which won’t get Noah rushing to build an ark.

Silver iodide is the chemical most often used and there are legitimate health and environmental questions about the levels. The EPA and state governments regulate all cloud seeding programs. And there are multiple studies that show the levels of silver collected from cloud seeding are more than a 1000 times lower than EPA standards for drinking water and therefore have very minor environmental, toxicological or health impacts.

So, did cloud seeding cause the two flooding events that took place between Feb. 3-8 and 18-19? Nope. As the Times reported, the body in charge of the project, the Santa Ana Watershed Project Authority (SAWPA), hadn’t even conducted any cloud seeding operations since Feb. 1, and even then, they didn’t do it in the San Diego area.

I didn’t intend to go up the whole cloud seeding hole, but the short encounter prompted me to think about the polarization in both the US and Canada, where people no longer debate different ideas based on a shared set of facts, but believe in different realities. Genuine, substantial conversations between people who disagree on key events, like say, the war in Gaza, are just not happening in places like college campuses — where they should — because each side sees the other as illegitimate, as if one is looking at fake clouds and the other at the real thing.

University administrators are now so fearful of getting involved in any way other than making anodyne statements — they don’t want to be “Harvarded” and alienate students, donors, and politicians or all three — that campuses have become bunkers of protest, not bastions of political debate.

It's also playing out politically in the US election cycle, where perception is driving reality. Look at the strong economic news. Last quarter, US GDP increased at a 3.2% annualized rate, business investment is up, consumer spending is up, the market is up and wages are up — but Biden’s poll numbers are down.

Biden is getting no credit for strong economic news and Donald Trump is sustaining no damage from bad legal news because partisan voters simply see what they want to see. Biden’s problem is no longer inflation itself — it has come down dramatically — it’s vibe-flation. Biden simply doesn’t look like the good news he’s delivering. He looks weak while his facts are strong. Trump looks strong while his facts are weak. And it’s working for Trump.

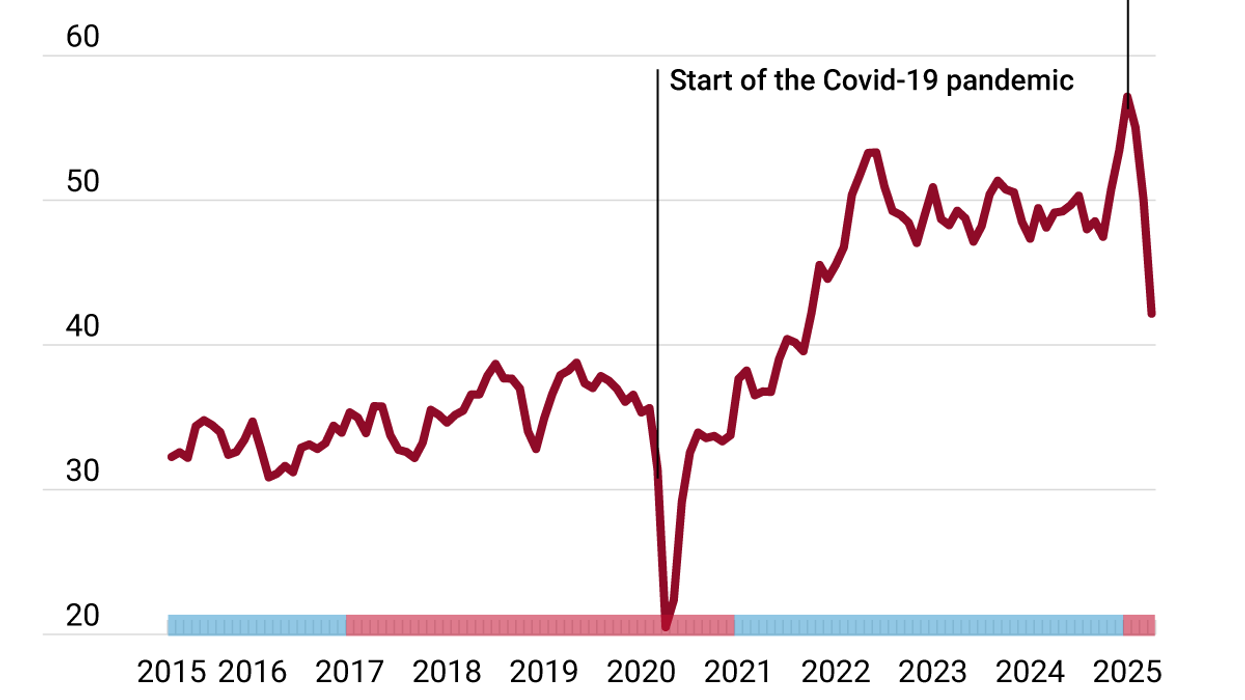

The self-reinforcing reality bubbles of partisan politics make it next to impossible to break out of these myopic views because there are no institutions with enough trust to set a benchmark of consensus and corrective facts.

As Gallup polling on trust consistently shows, confidence in US institutions is at all-time lows and going down: “The five worst-rated institutions — newspapers, the criminal justice system, television news, big business and Congress — stir confidence in less than 20% of Americans, with Congress, at 8%, the only one in single digits,” wrote Gallup’s Lydia Saad.

If someone doesn’t believe the clouds are real, why would they believe the facts about the economy are real?

Everything is political. That’s our mandate here at GZERO, but it doesn’t mean everything is up for grabs. Seeding clouds of doubt with conspiracy theories everywhere erodes the foundational gift of our democracy, which is to have passionate disagreements respectfully with our neighbors and still manage to get big things done together. To do that, facts matter.

That’s why, with crises growing all around the world and the election cycle whirling ever faster, we at GZERO are committed to having humane, non-partisan, robust coverage about different, conflicting points of view — but at least with an agreed upon set of basic facts. To alter an old saying, you are entitled to your own opinions, but not your own clouds.