In a special Sunday edition of Signal, we take stock of the geopolitical situation halfway through one of the most tumultuous years in recent memory. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine boosted Euro-Atlantic unity but deepened fault lines between the “West” and powerful emerging markets. A global food crisis still looms, and later this year we’ll see pivotal and extremely contentious elections in Brazil and the United States.

If the last six months are any indication, you’ll want to buckle up for the second half of the year.

-The Signal team

Resilience in an era of crisis

Willis Sparks

We live in an era of emergency. Since 2008, we’ve seen a global financial crisis, a sovereign debt crisis in Europe, and a wave of unrest that sparked political turmoil across North Africa and the Middle East. Civil wars in Syria and Libya helped trigger a migrant crisis that upended European politics. Then came Britain’s exit from the EU, the surprise election of a US president who upended the most basic assumptions about America’s role in the post-war world, and a political crisis in the wake of his defeat. Next came a global pandemic that has killed millions and continues to inflict human, economic, and political damage in every region of the world. Now we have Russia’s war on Ukraine, millions more refugees, and a global food emergency that has only just begun. All of that has happened in the past 14 years.

Given all that, it’s obvious that deeper investment is needed in resilience at every level of government, commerce, and society. In a world of shocks, we need good shock absorbers. Political and business leaders now face a basic choice. They can build networks of trade and political alliances with only like-minded partners – those with similar political systems, cultures, or overlapping interests – to ensure competitors and potential enemies can’t gain strategic advantages by exploiting weaknesses like monopolies on needed resources or supply-chain vulnerabilities. Or they can diversify their partnerships to build relationships where they make the most sense for economic value and the common good. It’s possible that governments will now use sanctions, tariffs, export bans, subsidies, and other forms of protectionism as everyday weapons to build resilience by enhancing security. Others will continue to seek resilience through a broader diversification of their partnerships.

This choice will be most obvious in relations between China and the West. Will the US and EU begin to treat China primarily as a political and economic opportunity or mainly as a security risk? Will China seek a more confrontational role toward the West and the international institutions where it has outsized power, or will it continue to define its security through the dynamism of its global trade and investment relationships?

These are the questions most likely to determine how well the global economy and current international system absorb the next generation of shocks.

The Graphic Truth

Beatrice Catena

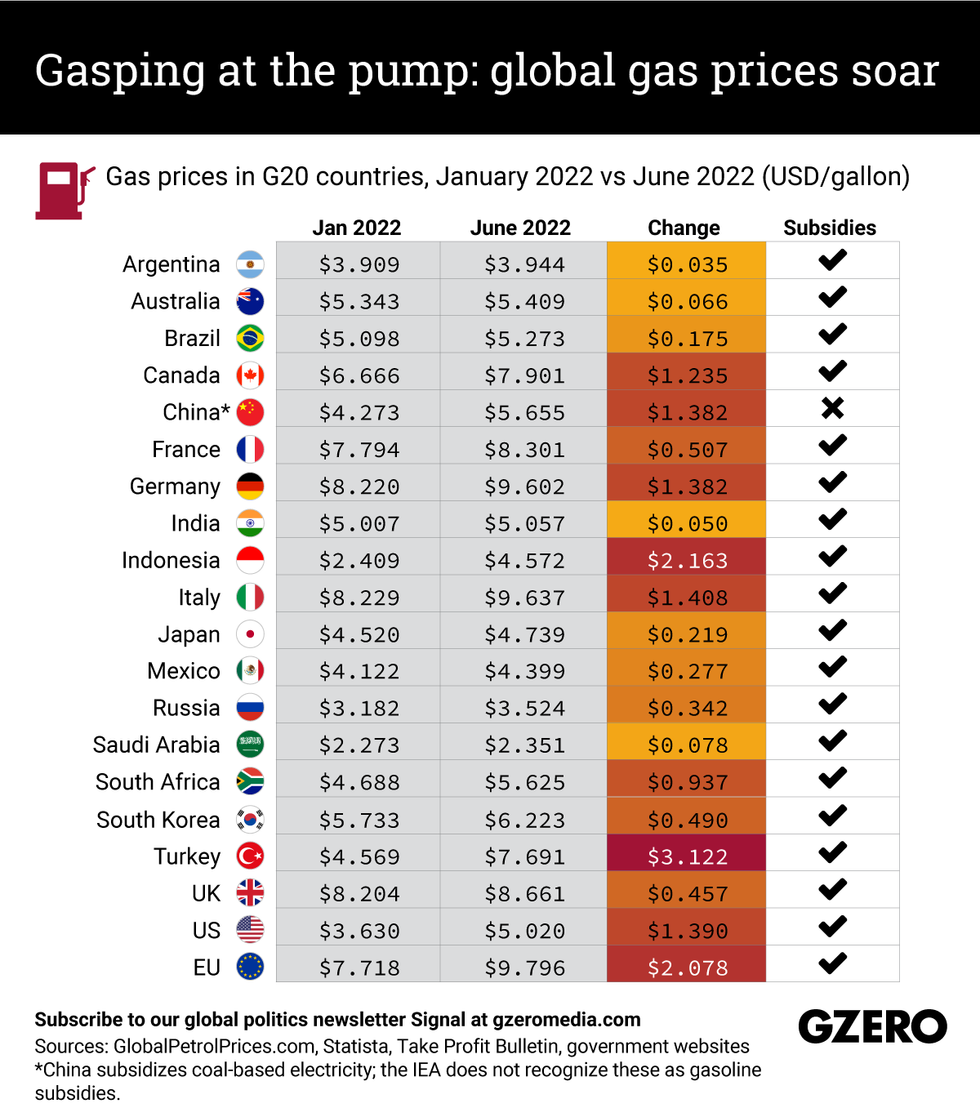

Beatrice CatenaPrices at the pump are soaring. Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, much of the world has been affected by the economic impact of sanctions, higher inflation, constrained supply, and overall uncertainty. In the G20 economies, consumers tend to complain most about the price of unleaded gas, which is affecting their ability to get around town and go on holiday. We look at how far north the G20’s gas prices have been driven.

CIO Strategy Webcast Series

Citi Private Bank

Citi Private BankJoin us each week on Thursday at 11:30am EST for a conversation with senior investment professionals and external thought leaders on timely market events and ask your most pressing questions.

Big bad bear market

Carlos Santamaria

Carlos SantamariaIf you're an American worker with a 401(k), you're probably worried about being in the claws of a certain furry animal everyone seems to be talking about these days.

We're referring to a bear market, a Wall Street term for when the value of stock indices like the Dow Jones Industrial or the S&P 500 fall under 20% or more from a recent peak for a sustained period of time. Since bears hibernate, it’s investor-speak for a market in retreat.

On June 13, the S&P 500 officially entered bear market territory — with big implications for both investors and people who are indirect participants in the stock market through their 401(k), America's most popular company-sponsored retirement account. Simply put, since your 401(k) is likely invested in stocks, the longer the current slump lasts, the less money you'll have for retirement.

But that's only true if the bear market is still ongoing when you retire.

In other words, if you can afford to wait it out, odds are that the bear will eventually be followed by a bull (market) — aka a cycle of expansion — once the current economic turmoil subsides. Still, you might have a problem if you're a baby boomer with only a few years left to reach retirement age, in which case you'll have to crunch the numbers to decide whether it's best to cash out now — with less money, and pay taxes on what you withdraw — or pin your hopes on a swift recovery.

The thing is, no one knows how long bear markets last. The average historical duration is about a year, but in the early 1970s the bear stayed in its cave for almost two years, the S&P 500 lost half its value, and the US economy took a whopping 69 months to completely recover.

During the 2007-2008 Great Recession, the S&P 500 decline was even sharper (57%) and the market only recovered after 49 months.

Will the bear be followed by an even scarier recession? Maybe, but it's not guaranteed.

One key difference between the current US bear market and previous ones that preceded recessions is that unemployment is still very low at 3.6%. When Americans start losing their jobs at a higher rate, though, that's likely a sign that a recession is on the way.

What’s more, with the Fed getting tough on interest rates to tame sky-high inflation, it’s certainly possible that the US economy won’t hit the Goldilocks “soft landing” of bringing inflation down to about 2% while avoiding a recession (two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth).

Regardless, “making any prediction is unusually fraught” now due to an unprecedented set of shocks, including COVID and the war in Ukraine, says Robert Kahn, Eurasia Group's director of Global Macro-Geoeconomics.

Still, he adds, a recession seems more likely than not. It'll be painful, but not necessarily a catastrophe.

“Recessions can be moderate in tone,” Kahn explains. And whether or not we get one, “we’re going to have tremendous uncertainty heading into this slowdown period about how that plays out.”

What We’re Watching: US and China's rocky marriage and India’s unlikely success

China-US: Bad politics, good economics

President Joe Biden is a very different president than his predecessor, Donald Trump. But on some foreign policy issues – notably managing relations with China – the two are kindred spirits. US-China relations crashed under Trump, and Biden has kept the relationship on a mostly combative footing, leaving Trump-era tariffs on some Chinese goods in place. Still, while the White House talks tough about isolating China geopolitically, speculation of a US-China “decoupling” is misplaced. Beijing and Washington need each other because their economies are closely intertwined. The US is China’s biggest trading partner, with Americans importing a whopping $541.5 billion worth of Chinese imports in 2021. Even in 2020 – a slower trading year amid the pandemic – China and the US traded $559.2 billion worth of goods. What’s more, two-way foreign direct investment, which is more resistant to economic shocks, has ballooned in recent years (Chinese FDI in the US increased 61% between 2015 and 2020). The resilience of the bilateral economic relationship is also reflected in the fact that China is the third-largest export market for American goods (behind Mexico and Canada). Support for a tough-on-China stance gets rare bipartisan support in Washington these days, so political ties between Beijing and Washington will likely remain rocky. Still, with their economic fortunes so closely linked, China and the US are in this marriage for the long haul.

How is India doing so well?

On the surface, India seems to be having a moment. With record-breaking monthly exports and a post-pandemic bounce-back of 8.7% GDP growth pushing the size of its economy to $3.3 trillion, Prime Minister Narendra Modi seems well on his way to meeting his goal of making the country a $5 trillion economy before long. Meanwhile, both Russia and the West are courting Delhi as a key ally these days. But beneath the surface, not all is well. Despite Modi’s ambitious economic reforms, inequality remains stubbornly high, and the war in Ukraine has worsened inflation. Unemployment, meanwhile, is at 7.8%. In a country with 360 million people under age 15, that’s a big long-term problem. Meanwhile, Modi’s move to ban wheat exports has angered its Western partners, while the anti-Muslim bent of Modi’s ruling BJP party has antagonized Delhi’s Gulf partners. And of course relations with China, the other billion-strong Asian heavyweight, are strained. Modi looks secure at home, with no real opposition and a compliant media, but things aren’t getting easier for the world’s most populous democracy.Podcast: Could today’s crisis lead to future growth?

If you’re peeking out from under the duvet, wondering how to make it to 2023, be sure to listen up. In our latest “Living Beyond Borders” podcast from Citi Private Bank and GZERO Media, we examine the global risks setting the world on edge at the halfway point of 2022.

New COVID strains, supply chain issues, Russia’s war in Ukraine, climate change, soaring inflation, geopolitical decouplings — these are just a handful of the bubbling crises roiling the markets and the international order.

To delve into what’s happening in the markets and the future of financial growth and globalization, Eurasia Group’s Managing Director for Climate and Sustainability Shari Friedman speaks with David Bailin, chief investment officer and global head of investments at Citi Global Wealth, and Ian Bremmer, president of Eurasia Group and GZERO Media. Listen to their discussion here.Hard Numbers: Global malnutrition alert, Europeans’ bleak view of economy, South Korea’s export crunch, Xi’s confidence

Gabrielle Debinski

Gabrielle Debinski8 million: Global food prices have risen amid the war in Ukraine, but it is particularly bad for emerging-market economies. UNICEF now says that up to 8 million children under the age of 5 could die from severe malnutrition in the coming months. The organization listed nearly two dozen “high risk” countries and urged developed states to step up and help.

-23.6: European confidence in the economy is going from bad to worse. The EU’s consumer confidence indicator for the eurozone plunged to -23.6 this month, the lowest it’s been since the peak of the pandemic in April 2020. Fears are mounting that the continent will soon fall into a recession as Russia tightens its grip on gas exports.

13: South Korean exports in the first 10 days of this month dropped 13% from the same period in 2021, a dramatic change from earlier this year when the country experienced an export boom amid the global post-pandemic recovery. The shift highlights the ongoing challenge for export-reliant economies amid the global inflation storm.

5.5: China’s economy has been pummeled by Beijing’s strict zero-COVID policy and a weakening housing market. But President Xi Jinping says his country is still on track to meet its 5.5% GDP growth goal this year. Economists, however, are skeptical and suggest it will be closer to 4%.

This edition of Signal was written by Beatrice Catena, Gabrielle Debinski, Alex Kliment, Willis Sparks, and Carlos Santamaria. Edited by Tracy Moran. Graphic by Ari Winkleman, art by Paige Fusco.