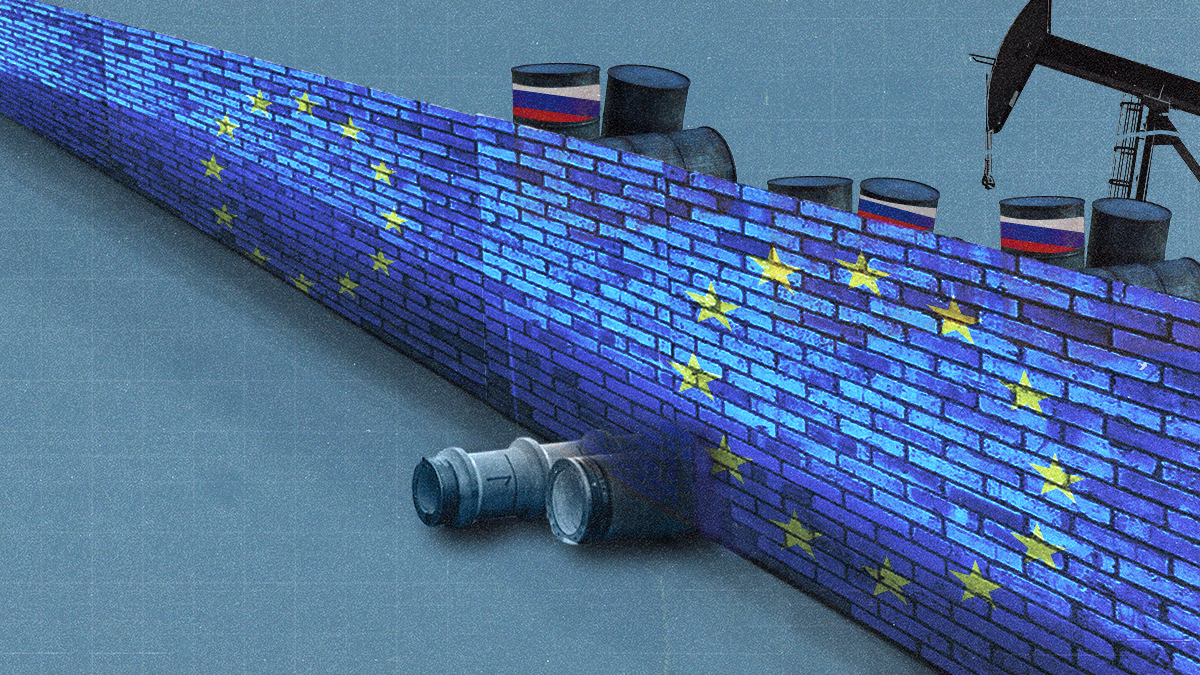

After months of diplomatic wrangling, it seemed this week like the European Union had finally made a big breakthrough in its effort to punish President Vladimir Putin for attacking Ukraine. Oil prices soared, and gas hit new highs after Brussels announced that it had reached an agreement to phase out Russian oil imports by the end of the year.

But the agreement also includes a slate of carve-outs and caveats that could dilute the bloc’s effort to decapitate the Kremlin’s war machine.

What’s in the deal?

The agreement includes a ban on all seaborne Russian oil imports by the end of the year. That covers about two-thirds of the bloc’s total crude imports from Russia – the remaining third comes via pipeline. And since Germany and Poland have pledged to voluntarily ditch oil brought in by pipeline as well, some 90% of Russian imports to Europe would be shut off by the end of the year.

Moreover, it also appears that the EU is set to ban insurance providers from covering tankers carrying Russian oil anywhere in the world. Given that British and other European companies dominate the marine insurance industry, this move will significantly undercut Russia’s ability to offset its losses by selling more oil to Asia.

What’s not in the package?

Part of the reason it’s been so hard to reach a deal is because of opposition from three landlocked EU member states: Hungary, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic. (Slovakia, for instance, gets almost 100% of its oil from Russia.) Hungary's PM Viktor Orbán, who is buddies with Putin, drove the hardest bargain and was most vocal in his refusal to sign onto a Russian oil embargo. He argued that such a move would be economically catastrophic for his country, which depends on Russian pipelines for 65% of its oil. Because the sanctions package requires unanimous approval from EU member states, the holdout would have killed the entire project.

To save face and avoid an embarrassing admission that it couldn’t strike a deal, Brussels capitulated to Budapest’s demands this week, saying that it will continue to allow imports via pipelines and will work out the precise end date for that exemption later.

Despite the obvious disconnect, both Brussels and Budapest are claiming victory. The EU has touted the deal as a triumph for European unity and the maximum pressure campaign against Moscow. Orbán, on the other hand, wrote on Facebook that “an agreement was reached. Hungary is exempt from the oil embargo!” This carve-out only accounts for 10% of Russian exports to the EU. Still, it means that Moscow will be able to continue shipping at least some exports to Europe.

Deferring thorny decision-making never works out well for the sprawling EU. “Agreeing on ending the exclusion of Russian oil delivered via pipelines will not be easy,” says Emre Peker, a Europe Director at Eurasia Group.

“It could take a few months, and even when a deal is done the extended phase-outs as proposed are likely to survive,” he says. So, can the EU still inflict significant pain on Russia if pipelines remain online? Peker says that will only be possible if “Brussels can forge consensus on curtailing Russia’s ability to export crude elsewhere” around the world.

Will Russia feel the pain?

The ban will undoubtedly hurt Russia. Losing two of its biggest crude importers – Germany and the Netherlands – is a big loss. Still, Asia continues to guzzle Russian oil, with China, the largest single purchaser, accounting for almost a third of all Russian crude exports, and South Korea accounting for roughly 7%. What’s more, Europe had already paid Russia 21 billion euros ($22.3 billion) for oil in the first few months since Putin invaded Ukraine. That’s a lot of money for Moscow’s ongoing war machine.

And even when things get rough, Russia can still sell oil for a discount. Notably, two mammoth economies – China and India – have opted not to join the West’s sanctions campaign against Russia. India, for its part, received more than 24 million barrels of Russian oil last month, up from about 3 million in March. China is also trying to make the most of a crude bargain.

What’s at stake for the West?

Indeed, while the insurer ban will make it much harder for Russia to sell its oil, it will also likely keep prices higher, revealing the extent to which Western states are willing to inflict pain on their own constituencies – even as inflation reaches record highs throughout the Eurozone – to punish Russia.

In adopting a hardline anti-Russia stance, EU member states also risk backlash at home where not everyone is on board with the plan: 62% of Slovaks, for instance, oppose ditching Russian oil. As energy prices continue to rise – and a deepening cost of living crisis sweeps the continent – European governments could be risking the revival of a fiery populist wave.

This comes to you from the Signal newsletter team of GZERO Media. Subscribe for your free daily Signal today.