French President Emmanuel Macron made headlines over the weekend when he called for the West not to "humiliate" Russia in its war against Ukraine "so that the day when the fighting stops we can build an exit ramp through diplomatic means."

The statement drew ire from the Ukrainian government. Ukraine’s foreign minister Dmytro Kuleba bristled at the suggestion, saying such calls “only humiliate France” because Russia “humiliates itself”

President Volodymyr Zelensky, for his part, seemed perplexed by the thought that he should be wary not to humiliate Russia when "for eight years they have been killing us."

Want to understand the world a little better? Subscribe to GZERO Daily by Ian Bremmer for free and get new posts delivered to your inbox every week.

I share his sentiment. It is immoral to ask Ukrainians to show restraint or moderate their war aims in order to help Russian President Vladimir Putin "save face." He started this war unprovoked. The only alternative to humiliating Russia is to let it win—no doubt an unacceptable outcome for Ukraine, and one only Ukrainians have the right to accept, anyway.

Statements like Macron’s undermine Ukrainian sovereignty and weaken the Western front against Russia. They signal to Putin that time is on his side: that if only he can take and hold all the Donbas and keep the land bridge to Crimea, he can outlast the West. Pressuring Kyiv to accept a ceasefire before it has retaken all of its lost territory would de facto codify Russia’s gains—precisely what Putin wants. As such, these calls make it more, not less, likely that Putin stays the course in his war of conquest against Ukraine.

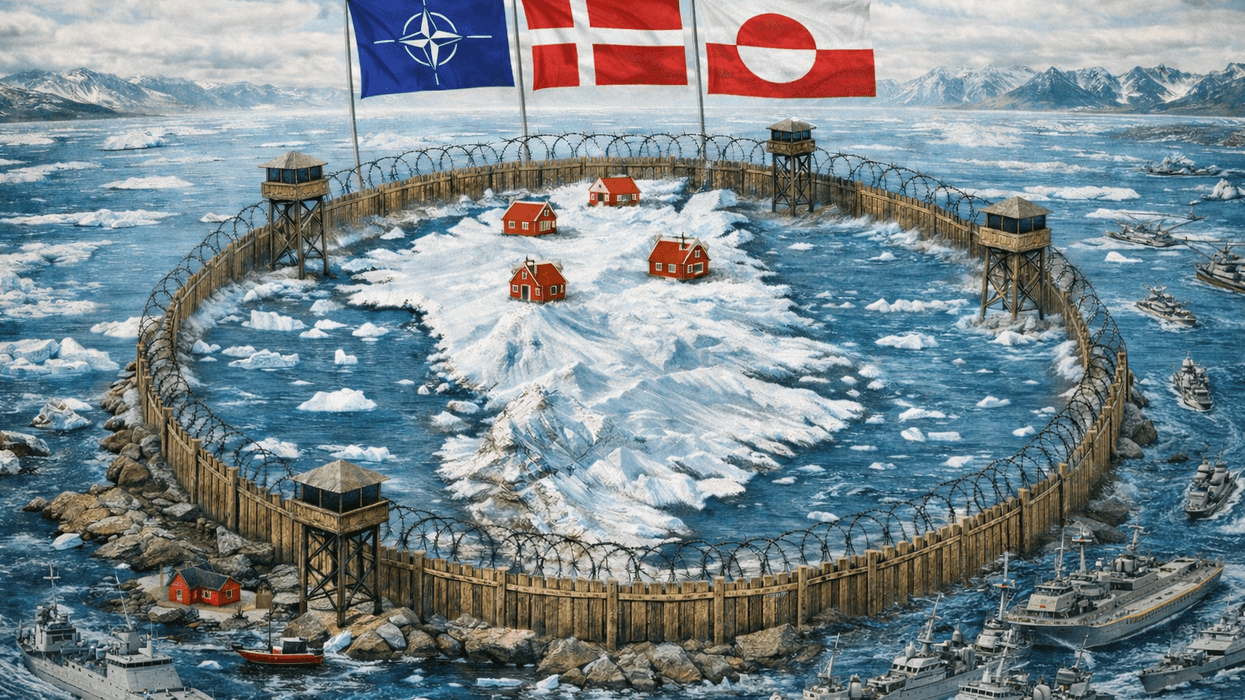

That doesn’t mean Russia has a path to victory. As I’ve written before, no matter what happens on the battlefield, Putin’s invasion of Ukraine will turn out to be a catastrophic strategic mistake. Zelensky is an international hero, and Ukraine is now decidedly anti-Russian. The transatlantic alliance has a newfound sense of purpose. Europe is increasing its military spend. NATO is expanding both its membership and its activities along Russia’s borders. American and European sanctions are effectively permanent, and they will cause significant long-term damage to the Russian economy. There’s no conceivable scenario in which Russia comes out of this war economically and geopolitically stronger than before February 24.

But when it comes to the narrow fight for the Donbas—Putin’s stated goal for the "second phase" of the "special military operation"—calls to negotiate with Russia even as it continues to mercilessly shell Ukrainian cities make it easier for Putin to claim a win there.

As poorly conceived as it was, though, Macron’s statement was no slip of the tongue. The French president has repeatedly insisted that Russian President Vladimir Putin should be incentivized to end the war as soon as possible, even if it means pressuring the Ukrainians to voluntarily cede part of their territory to Russia.

And he’s not alone in calling for Putin to be appeased. Whether in private or in public, the leaders of Germany and Italy have also urged Ukraine to make some sort of compromise with Russia in recent weeks, as have former U.S. secretary of state Henry Kissinger and the New York Times editorial board.

What’s happening is that as the conflict settles into aprotracted yet unstable stalemate, the triumphalist mood that permeated European capitals until recently has turned gloomy. Russia is making slow but steady territorial gains in the Donbas, and despite their valiant efforts, Ukrainian forces are displaying wear and tear. It’s becoming clear that neither side will be able to achieve a decisive victory anytime soon.

In the meantime, however, global growth, inflation, energy prices, and food shortages are getting worse. The prospect of an unending “war of attrition,” as NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg called it, has some leaders starting to wonder aloud about the impact of a long slog on their own economies and politics.

In their eyes, those like Macron who believe that Ukrainians can’t win, that Russians will eventually be able to capture and hold most of the Donbas, that sanctions will hurt the West more than they hurt Russia—they are trying to get ahead of the inevitable outcome. Whether the Ukrainians agree or not, they think it’s better for everyone to freeze the conflict sooner rather than later, preventing unnecessary Ukrainian bloodshed, global economic pain, and political upheaval.

There are, of course, exceptions to this position: the Americans, the British, the Finns, the Swedes, the Poles, and the Baltics are still committed to helping Ukraine recapture their territory, believing only Ukrainians can determine when enough is enough. Kyiv’s official position is that Ukraine will keep fighting until the country’s full territorial integrity has been restored—or at the very least, until Russian forces are pushed out of the territory they have occupied since February 24.

So far the Biden administration has managed to keep the coalition together in support of Ukraine’s war aims, but its ability to continue to do so over the coming three to six months will be increasingly tested.

After more than 100 days of near-absolute unity, cracks in the Western front are starting to show.

🔔 And if you haven't already, don't forget to subscribe to my free newsletter, GZERO Daily by Ian Bremmer, to get new posts delivered to your inbox.