News

Electoral violence comes out of the shadows

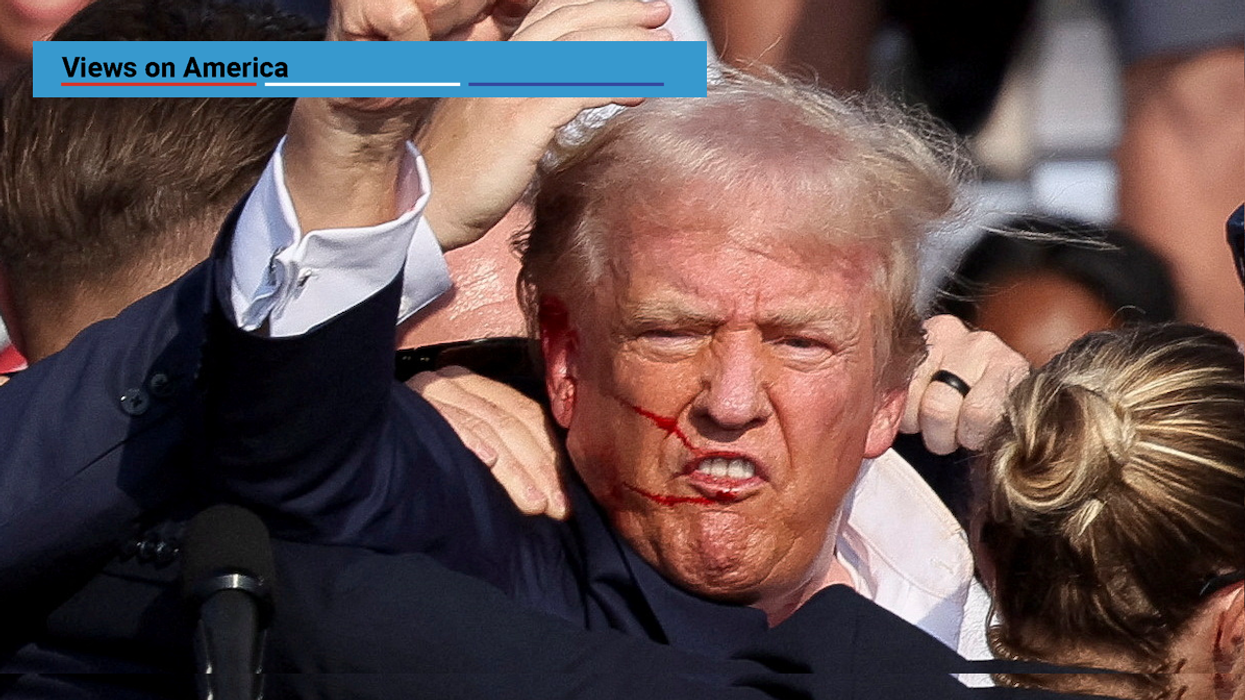

The brazen assassination attempt on former President Donald Trump this weekend has pulled from the shadows an inevitable implication of the country’s polarization: the risk of political violence. In this consequential US election year, with questions of institutional legitimacy hanging in the air, misinformation flooding social media, and worries about the fitness of at least one of the candidates, we have now been alerted to how real the threat of violence is for the months ahead.

Jul 15, 2024