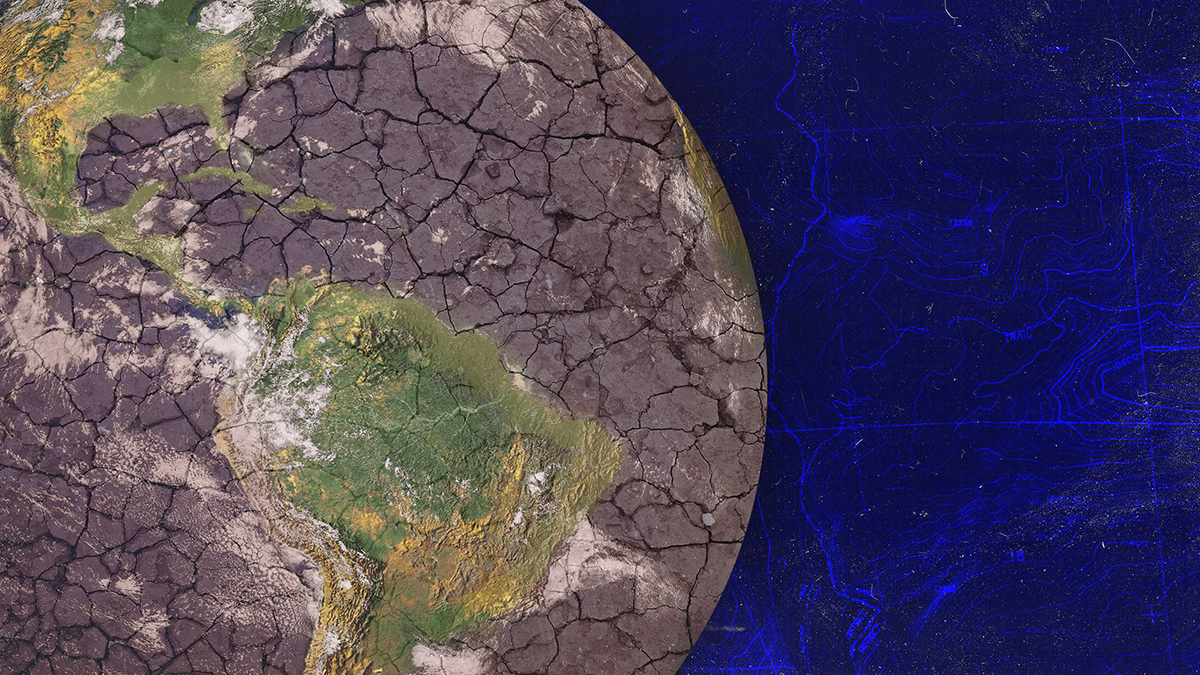

This might be the year that the world finally acknowledges its mounting water crisis. From France to Zimbabwe and from the US to Chile, water shortages will drive new social and political conflicts. Rich developed countries will no longer be able to ignore the problem as one solely afflicting poor countries of the Global South. Against this backdrop, the UN is holding its first water conference in nearly 50 years from March 22-24 in New York.

We asked Eurasia Group expert Franck Gbaguidi what to expect from the UN conference and from efforts to address water scarcity in the year ahead.

Who will be at the UN conference and what will they discuss?

Over 6,500 participants are expected – mostly policymakers, NGO representatives, and water experts. Unlike the previous UN water conference in 1977, private sector actors will show up en masse, as they have at other recent environmental summits. The three-day event is meant to be both a wake-up call and a call to action. A wake-up call because the gap between water supply and demand is expected to reach 40% in just eight years, making life as we know it virtually impossible for millions, if not billions, of people. A call to action because governments and companies are asked to make voluntary yet ambitious commitments that will form a “Water Action Agenda” at the conference. It is a bottom-up approach, which means that these commitments must be bold, targeted, and measurable to make a real difference. Progress on pledges and targets will then be monitored over time, with the hope of significantly reducing the supply-demand gap by 2030.

What is driving water scarcity?

A couple of things. On the one hand, climate change is causing what we call “physical water scarcity” by squeezing water supply as the planet gets hotter. Warmer temperatures lead to more evaporation and less rainfall. On the other hand, poor infrastructure and a lack of proper water management fuel what we call “economic water scarcity.” Compounding both issues is the fact that the global population just reached 8 billion people, placing significant pressure on already strained resources.

What are some key geographic areas of stress you would highlight?

Water stress does not discriminate, but the impacts vary in severity. Shortages are particularly acute in the Middle East, home to nine of the ten most water-scarce countries in the world. In Africa, one in three people will face water scarcity this year, with the eastern part of the continent being the main hotspot. The western US will continue to suffer from its worst megadrought in over 1,200 years, despite recent heavy snow and rain. Elsewhere, countries including France and Spain in Europe, Mexico and Chile in Latin America, and China and India in Asia are bracing themselves for water shortages later in the year.

What will be the social and political consequences?

We expect to see a record number of water-related conflicts this year. In France, plans to build mega reservoirs are increasingly viewed as an attempt to privatize a public good and as counterproductive given the high risk of evaporation. As a result, protests are multiplying across the country, with activists committing acts of sabotage, leading the government to deploy police officers near reservoir sites. In Zambia and Zimbabwe, depleting water resources are heightening tensions between the two countries. That’s because Zimbabwe used up its water quota from their shared dam despite warnings from the Zambezi River Authority, which manages the dam and is jointly owned by both countries. Water scarcity will also be a catalyst for social instability, displacing populations in Iraq, Syria, and Yemen, threatening economic prospects in Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia, and heightening food insecurity in Kenya, Somalia, and Sudan.

How have governments been responding to this challenge?

They continue to treat water stress as a temporary issue. It’s a case of managerial myopia – they focus on emergency measures that abruptly disrupt, restrict, and redistribute resources. There are many such examples from the past couple of months. Western Australian authorities announced they will cut the water allotment of a mining company by one-third to save supply in the region. In Arizona, dwindling water availability is leading officials to deny permits for new real estate projects relying exclusively on groundwater resources. In February, Spain raised the level below which no extraction is allowed from rivers in the south of the country. As a result, agricultural output in the region is set to decline considerably, potentially jeopardizing the livelihoods of 25,000 workers. Meanwhile, the country’s northeastern Catalonia region has also put in place new restrictions, including a 40% cut in the water available for agriculture. In sum, disruptive and uncoordinated water-related measures in both rich and poor countries will likely be a fixture this year.

What types of new approaches are needed?

Water stress requires a shift from crisis measures to long-term solutions. Governments should focus on longstanding water management deficiencies by upgrading aging infrastructure, fixing system leaks, and improving tracking and billing capacities. They should provide incentives to ramp up research on water stress modeling, finance wastewater treatment solutions, and develop new technologies at scale. Currently, technologies such as those used in desalination plants are too expensive to be used in agriculture, which accounts for 70% of global water use. Overall, greater coordination is needed among all stakeholders involved, from local policymakers and large investors to water-intensive industries and rural households. The UN water conference will hopefully be a step in the right direction.