After 16 years under Chancellor Angela Merkel’s steady hand, Germans are heading to the polls this Sunday to elect a new government. The candidate of the party with the most votes will initiate coalition talks with other parties to secure a majority of the Bundestag’s—Germany’s federal parliament—598 regular seats.

But this election will be unlike any other. It’s the first time in Germany’s modern history that the incumbent leader does not stand for re-election. Yet Merkel, who has been described as the world’s most powerful woman and the de facto leader of Europe, remains a beloved and broadly popular figure even after serving four consecutive terms.

Angela Merkel feeds Australian lorises at a bird park. (Georg Wendt/picture alliance via Getty Images)

Angela Merkel feeds Australian lorises at a bird park. (Georg Wendt/picture alliance via Getty Images)

That means that rather than a choice between continuity and renewal, this election is a referendum on which candidate can best fill Merkel’s shoes.

Want to understand the world a little better? Subscribe to GZERO Daily by Ian Bremmer for free and get new posts delivered to your inbox every week.

Who’s who?

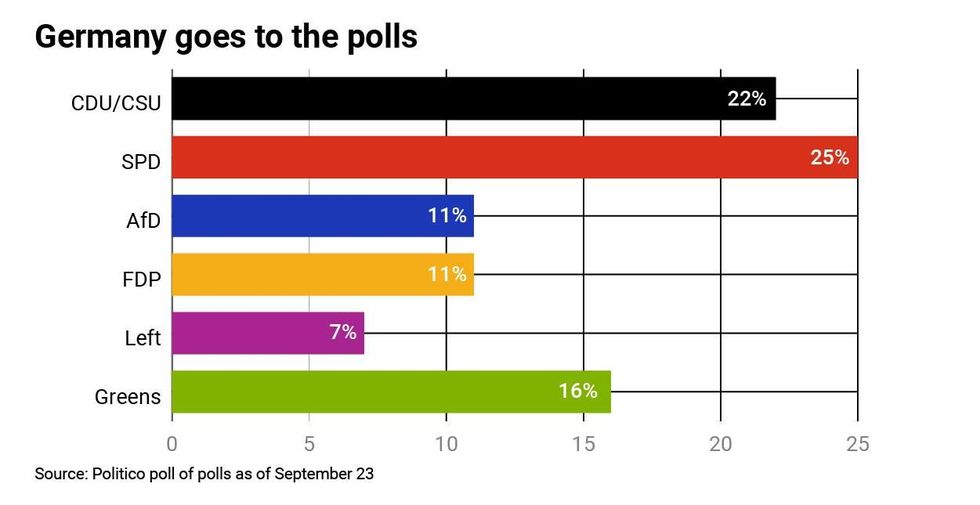

The center-left Social Democratic Party (SPD) currently leads the polls with 25 percent of voting intention. The party has been on and off the government in recent decades, in a grand coalition with the CDU/CSU during Angela Merkel’s first, third and fourth (i.e., current) cabinets. In the last federal election in 2017, the SPD suffered its worst result since WWII. The SPD’s candidate for chancellor, Olaf Scholtz, is Germany’s sitting vice-chancellor and finance minister, and was formerly the mayor of Hamburg. A charismatic technocrat, Scholtz has done well on the campaign trail despite early setbacks, winning all the major TV debates, and is widely seen as the closest figure to Merkel in terms of capabilities, executive experience, and gravitas.

Olaf Scholz campaigning in Münster.Guido Kirchner/picture alliance via Getty Image

Olaf Scholz campaigning in Münster.Guido Kirchner/picture alliance via Getty Image

The center-right CDU/CSU, a Christian-democratic alliance of the Christian Democratic Union of Germany (CDU) and the Christian Social Union in Bavaria (CSU) known as the Union, trails the SPD closely with 22 percent of voting intention. The CDU/CSU has been in government since 2005 with Merkel as chancellor and was led by her from 2000 until she retired from CDU leadership in 2018, after the bloc recorded its worst result since 1949 in the 2017 federal election. Merkel’s successor as CDU/CSU party leader and chancellor candidate is Armin Laschet, the sitting governor of Germany’s most populous state, North Rhine-Westphalia. Laschet led the race for much of the year, but his poll numbers nosedived after he was caught laughing during a visit to a flood-stricken town in July. It also hasn't helped his flagging campaign that Merkel's support for him has been lukewarm at best, staying out of it altogether until very recently.

Armin Laschet laughs after the floods in North Rhine-Westphalia.(Marius Becker/picture alliance via Getty Images)

Armin Laschet laughs after the floods in North Rhine-Westphalia.(Marius Becker/picture alliance via Getty Images)

The environmentalist and socially progressive Greens are polling in third place with 16 percent of voting intention. A minor opposition party during Merkel’s four governments, the Greens have seen a groundswell of support over the last four years that has catapulted them to center stage, having placed second nationwide in the 2019 European Parliament election. Annalena Baerbock, the Greens’ candidate for chancellor, is a pragmatic centrist. The only top candidate representing a real break with the past, she led the polls briefly in late-April/early-May 2021, but her popularity took a serious hit after she was implicated in a series of scandals involving alleged financial malfeasance and plagiarism.

Annalena Baerbock speaks at a Greens Party congress.(Sean Gallup/Getty Images)

Annalena Baerbock speaks at a Greens Party congress.(Sean Gallup/Getty Images)

The Free Democratic Party (FDP), a classical-liberal party that sits in opposition to the Merkel government, is polling around 11 percent of the voting intention. The FDP formed a center-right coalition government with the CDU/CSU between 2009 and 2012 but failed to win enough votes to stay in parliament during the 2013 federal election, although it later regained its representation in 2017. The FDP’s leader and chancellor candidate, Christian Lindner, is running on a libertarian, pro-business platform.

Christian Lindner speaks during a press statement before the parliamentary group meeting in the Bundestag.(Michael Kappeler/picture alliance via Getty Images)

Christian Lindner speaks during a press statement before the parliamentary group meeting in the Bundestag.(Michael Kappeler/picture alliance via Getty Images)

Finally, there’s the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) polling at 11 percent and the far-left Left Party (DL) polling at 7 percent. Neither of these populist and anti-establishment parties has been in government before. Although both are unlikely to find themselves in any plausible coalition government (and AfD much more so than the Left), they will continue to define the fringes of German politics and bleed working-class voters from more moderate parties.

What’s likely to happen?

With just two days until the federal elections, the race to lead the coalition talks has narrowed to two contenders, with the SPD’s Olaf Scholz enjoying a solid edge over Merkel’s chosen successor, Armin Laschet. But barring any major unexpected developments, it is almost certain that at least three parties will be necessary to build a government. This increases uncertainty about possible coalition outcomes. At the same time, parties’ policy red lines and political realities constrain the number of likely combinations.

As of September 24, the most likely scenario is an SPD-led coalition with the FDP and the Greens, with Scholz as chancellor. This so-called “traffic light coalition”—named after the parties’ colors (red, yellow and green, respectively)—will be more likely to materialize the wider the gap between the SPD and the CDU/CSU turns out to be.

However, if the CDU/CSU outperforms expectations and comes within striking distance of the SPD, the traffic light coalition would become less viable. In that case, a CDU/CSU-led “Jamaica coalition” (owing to the center-right bloc’s customary color, black) with the FDP and Greens and Laschet as chancellor would become likely.

Other configurations remain possible. And the race is still wide open due to a high number of undecided voters, estimated at one-third of the electorate.

What’s at stake?

No matter what, Germany will have a centrist, moderate government that supports a strong Europe, multilateralism, the rule of law, and a working social contract.

Yes, there could be differences between the coalitions in terms of fiscal policy and climate ambition. Under a traffic light government, deficit spending and infrastructure investment would increase and the debt brake would remain suspended for longer, while the Greens would have more latitude to enact their climate change priorities. Under a Jamaica coalition, the FDP would have freer rein to lower taxes and the Greens would conversely have reduced leverage on climate.

But the differences will be minor.

And when it comes to foreign policy, the daylight between the coalitions is dimmer still, with all the top parties roughly aligned in defense of continuity (the exception being the Greens’ opposition to NATO defense spending targets and nuclear sharing). The tone against Russia and China may harden some, but Nord Stream 2 will move forward and Germany will continue to deepen its economic ties with Beijing, despite remaining a steadfast US ally on security and human rights.

The greatest change will be on the international stage, where Angela Merkel’s leadership will be sorely missed. Not because of policy differences, but because there is no one in Germany, Europe or the West that can match the level of respect, authority, and trust Mutti commands over allies and adversaries alike.

In Europe, her departure will leave a void that neither Laschet nor Scholz will be able to fill. Nor will Italy’s Mario Draghi, the admittedly impressive premier of a European middle power, or France’s Emmanuel Macron, embroiled in a presidential election of his own in 2022 and whose divisive personality makes him less suited for the role, anyway.

All of this means that Germany will be less able to demonstrate leadership at the European level, and Europe will lose global influence.

As it turns out, what matters to the world is less who the next German chancellor is than who it isn’t.

🔔 And if you haven't already, don't forget to subscribe to my free newsletter, GZERO Daily by Ian Bremmer, to get new posts delivered to your inbox.