If you are worried the attempted assassination of Donald Trump is likely to lead to more political violence in the United States in the months ahead, you are in good company.

The people who spend their careers studying the question are rattled.

“If the election is close, I expect violence of various sorts,” says Rachel Kleinfeld, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Kleinfeld, whose 2018 book, “A Savage Order,” set out a framework for understanding political violence around the world, is afraid that more American blood will be spilled. This is partly because bad things tend to happen in countries — like the United States — that have a history of political violence.

Kleinfeld pointed out in a recent podcast that Trump has encouraged the intimidation of election workers in swing states, used violent rhetoric about Republicans, like Liz Cheney, who express concern about his anti-democratic tendencies, and uses violence or the threat of it to rally his base.

“I’m not worried about that kind of civil war,” she said. “I am worried about targeted political violence.”

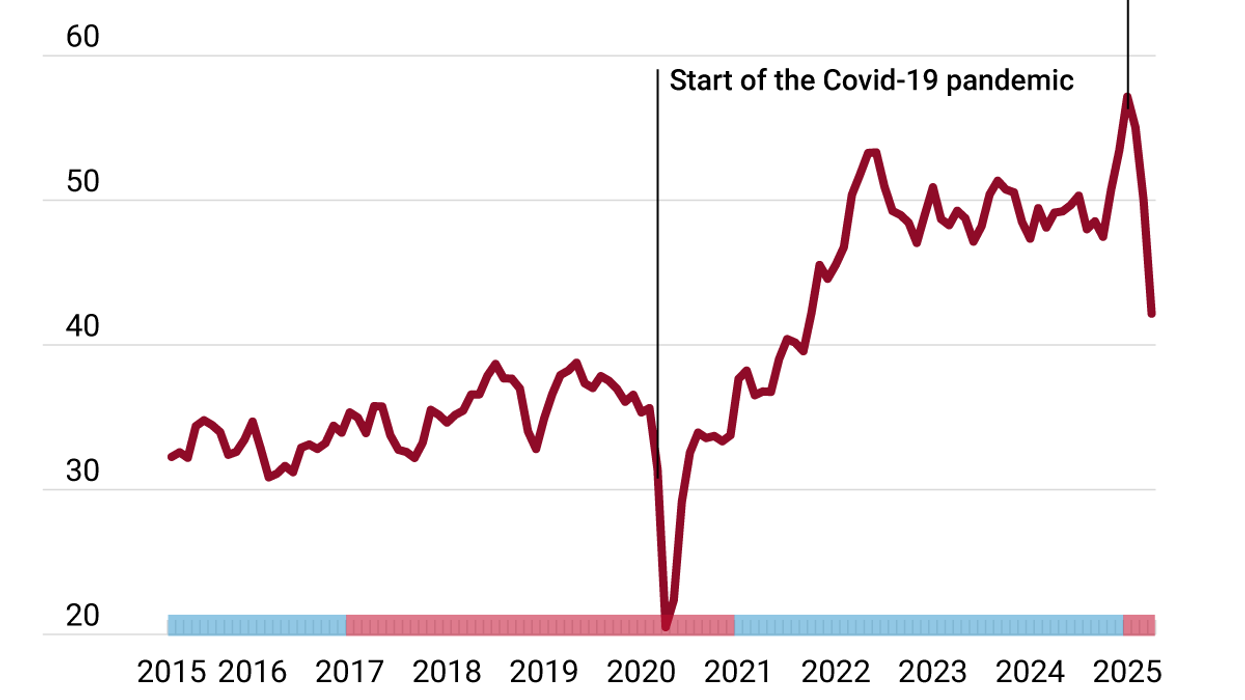

Kleinfeld has been warning about the potential for violence in the United States because of the changing mood in the country. Increasing numbers of Americans think it is justified, on both the right and the left.

About 18 million Americans support the use of force to restore Trump to the presidency, but more — 26 million — believe violence is justified to stop that from happening, according to a recent national survey conducted by University of Chicago professor of political science Robert Pape.

Americans are aware of the increased danger. In a YouGov poll taken after Saturday’s assassination attempt, 67% of respondents said the current environment makes politically motivated violence “more likely.”

Hate crimes are up dramatically — as are threats to Congress. The FBI revealed that a record-setting 11,643 hate crimes were reported by police in 2022, and the ADL has seen a surge in antisemitism in the wake of Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack on Israel.

Kleinfeld says there’s no reason to expect a civil war — but that’s because the US military is too powerful to be challenged.

‘You don’t need a civil war’

But full-scale war isn’t necessary when strategic use of political violence will do — or when it can help one side achieve its goals within a democracy. “You don’t need a civil war to try to take over a party with violence, and you don’t need a civil war to try to build your base with violence,” Kleinfeld said in a recent podcast.

The assassination attempt — which is as yet poorly understood — aligns with a story Trump supporters believe, says Amarnath Amarasingam, an extremism researcher at Queens University in Kingston, Ontario. It “fits into everything that the Trump team and MAGA Republicans have been saying since 2015 — that there is a kind of deep-state evil force that’s trying to stop Trump.”

Many Trump supporters still believe the 2020 election was stolen. As of last September, a whopping 63% of Republicans believed Biden’s win was illegitimate, despite evidence to the contrary. Now, Trump’s legal cases and convictions are being characterized as more ways to try to bring him down.

“When all of that failed, here you have them actually trying to kill him,” they think, says Amarasingam.

What fuels the extreme rhetoric?

The sense of a struggle for survival on both sides increases the risk of reprisals, and of more political violence, says Amarasingam. “This is kind of the core of how we think about extremist movements. Once you see an existential threat to you and your in-group, you and your people, then violence is acceptable.”

Lindsay Newman, Eurasia Group’s head of global macro-geopolitics, also believes the risk may get greater after the election but notes that it is unclear whether the risk will come only from the right.

“What do you think happens if Trump wins? What does everybody do? Do all the voters who voted for Biden, or for not-Trump, go home and just wait their turn for next time? What do you think happens if Biden wins? Do all those people who voted for Trump just go home and wait for their next time?,” she wonders.

Most Americans are opposed to political violence, but increasingly large minorities on both sides are not. “Not all of them are going to take up any sort of acts of violence, but some portion of those people will be aggrieved, will be deeply aggrieved,” says Newman.

“And what happens to them? Do they protest? Do the protests turn violent?”

Can the campaigns use this moment to find unity?

It seems unlikely the two campaigns will stop using rhetoric that is convincing so many Americans that the election represents an existential struggle.

After the assassination attempt, Republican Sen. JD Vance blamed Biden for portraying Trump as ”an authoritarian fascist who must be stopped at all costs,” saying that rhetoric “led directly to President Trump’s attempted assassination.”

Joe Biden delivered a speech calling for unity, but he is continuing to call Trump a “threat to democracy,” which seems to be a necessary part of his struggling campaign.

And on Monday, Trump named Vance as his vice presidential candidate, after which the crowd at the Republican National Convention in Milwaukee chanted, “Fight, fight, fight,” echoing Trump’s defiant words after an assassin’s bullet almost ended his life.

The trouble is, neither side can afford to stop using the rhetoric that is encouraging their supporters to see November’s election in such stark terms that they feel they are right to fight.