You’re leaving your role as president of the Canadian Chamber of Commerce after 17 years, which has been a transformative time. What is the biggest economic challenge facing Canada's trade with the US?

Perrin: The politics of trade has undergone a sea change in the US under the last two presidents. Previous presidents, from Ronald Reagan on, viewed America's interactions in the global economy as an opportunity to foster American prosperity, and they saw an integrated North American economy as a source of strength. More recently, however, US politicians have started to turn inward, increasingly viewing their country as a victim, and not as the primary beneficiary of international engagement. This change has led them to increasingly align themselves with domestic protectionists who want to build economic walls along the US border.

Unfortunately, this turn inward has coincided with a complacency here in Canada about our most important bilateral relationship. Even the best of friends can't afford to take each other for granted, or they will soon drift apart.

As Canada's relationship with the US has moved from being strategic to being transactional, American leaders are increasingly looking at each issue as a standalone, and they are making their decisions, not on what is in America's long-term best interest, but on where they can find immediate political advantage at home.

We need to rebuild that strategic relationship. It's vital for Canada to be seen as bringing solutions to the major problems confronting the United States, as opposed to simply pleading to be exempted from the latest punitive measure. We need to demonstrate, both in Washington and far away from it that Canada should be treated not as a problem, but as a partner.

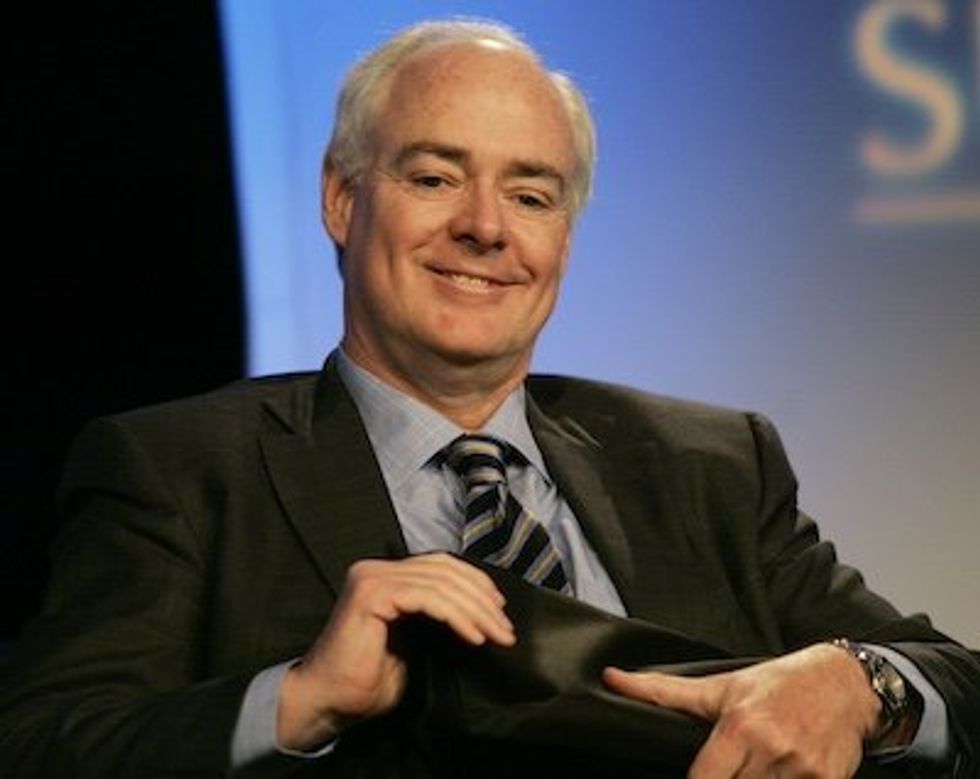

Perrin Beatty, outgoing president and CEO of Canadian Chamber of Commerce. REUTERS/Rebecca Cook

Perrin Beatty, outgoing president and CEO of Canadian Chamber of Commerce. REUTERS/Rebecca Cook

You recently said: “Canada is increasingly being viewed by our partners in the region as a well-meaning but unserious player on the international stage." In what ways has Canada become an "unserious player," and what needs to happen to change that reputation?

Perrin: Unfortunately, we have come to see ourselves as a moral superpower whose job is to tell everyone else what they are doing wrong. And we expect them to be grateful to us for it. Too often, we are driven more by a desire for good feelings than for good results. In contrast, other countries are both faster-moving and more engaged in the issues their interlocutors consider most important. The consequence is that, where the US and other countries used to ask, “How do we get the Canadians involved?” their question is now, “Should we inform the Canadians?” The fact that we learned about the AUKUS agreement at the same time as everyone else is just one example.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine two years ago should have been seen by Canada as world-changing, and our response should have been both meaningful and swift, with us marshaling what we have to offer in defense of the democracies. For example, Canada has an abundance of the “three F’s” – food, fuel, and fertilizer – and critical minerals that are essential to global stability. What we lack is the infrastructure, the vision, and the will to bring them to global markets to give countries an alternative to sending dollars to despots. This could be Canada's moment, but only if we are prepared to seize it.

You were a former defense minister under Mr. Mulroney, so you know about dealing with a dangerous world. But now, everyone is looking at the impact of the US election. Are we headed into a period of instability, conflict, and the dismantling of both trade and defense alliances that have been built since World War II?

Perrin: The problems we face, from global poverty to pandemics to wars to global climate change, all require an effective, coordinated international response. Instead of that, we are witnessing countries turning inward on themselves, as well as the increasing ineffectiveness of global institutions like the UN, the World Trade Organization, and the WHO in actually resolving issues that go to our very survival.

When I was privileged to be in government, there was a sense that, when the leaders of the G7 – leaders who included Reagan, Thatcher, Mitterrand, Kohl, and Mulroney – came together, problems would be resolved. Today, when international meetings take place, you get the feeling that our problems are bigger than our leaders. In fairness, the world is a much more complex and dangerous place today, but that's precisely why we need leaders whose vision, determination, and morality are up to the challenge. As your question suggests, we're at a crossroads that will determine whether we will be able to maintain the institutions and strategies that have guaranteed democracy, peace, and prosperity since the Second World War. The stakes have never been higher.

AI is both a transformative opportunity and a destabilizing threat. What is your view of how will impact business?

Perrin: Like businesses the world over, Canadian businesses will be transformed either for the better or for the worse by AI. AI, like the nuclear genie, can't be put back into the bottle. Our challenge is first to understand it, then to decide how to mitigate its potential bad effects, and then to determine how to unleash its positive aspects. In this instance, the technology is developing at a pace that far outstrips our capacity to understand it and manage it well. However, calls to initiate some sort of a standstill until we have thought these things through are naïve and unworkable; all that would happen is that the unscrupulous players would widen their lead.

The challenge for Canadian policymakers is how to successfully work with others on coordinated policies that limit the dangerous aspects of AI without denying its benefits to our industry and our society.

If there is a second Trump Presidency, what should Canada expect from the 2026 review/renegotiation of USMCA trade deal?

Perrin: Many Canadians expected that when Joe Biden became president, he would reverse the Trump protectionist measures. However, that assumption overlooked the fact that, in the past, Republicans were more in favor of free trade, while Democrats were more protectionist. In fact, the Biden administration has actually deepened some of the protectionist policies initiated by Donald Trump.

The danger is that the election will be a contest between two candidates trying to demonstrate who is more protectionist. Canadians must respect the right of US voters to determine their own government, just as we would insist on the Americans respecting our rights, but we need to demonstrate that it is in Americans' self-interest to foster a stronger relationship with their closest neighbor and best friend. And we must do that, not by special pleading, but by coming up with solutions to problems.

Finally, what is the best-case scenario for the US-Canada relationship in terms of economic prosperity and security? Is there a way to slalom through the protectionism, AI disruptions, political polarization, climate challenges, and conflicts and see a time of increased joint prosperity?

Perrin: The best-case scenario is that we restore a strategic partnership with the world's greatest superpower. We've let the relationship slide for too long, and it won't be easy to regain that position. But I believe it can be done if we muster the vision and the will to make it happen.

Last thing: You worked for Brian Mulroney, who recently passed away. He was the architect of the North American Free Trade Agreement and worked closely with Ronald Reagan. What lesson can today’s leaders learn from that time?

Perrin: As Canadians commemorate Brian Mulroney, our leaders should ask what they can learn from Canada's last great transformative prime minister. Brian Mulroney understood that governments don't create jobs and prosperity, businesses do. He also knew that the best way to solve problems was not to shut people out but to bring them in.

It's impossible to say exactly what policies a different government would follow, but what we do know is that our economy and our country are under severe strain today. The leader history will remember best will be the one who brings people together again in what remains the most fortunate country on the face of the globe.