“For India, AI stands for all inclusive,” reads the billboard outside this week’s AI Impact Summit in New Delhi organized by the Indian government, the first major gathering on the subject in the Global South. Alongside the slogan is an image of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, whose ambitions for the country of 1.5 billion people are clear: to become a technological superpower.

Big Tech executives and an array of political leaders have gathered in the Indian capital for the third summit in a global series on AI governance and development, with side events co-hosted by the United Nations. The heads of Google, OpenAI, and Anthropic are all there. India is looking to position itself as a prime destination for investment in data centers, AI infrastructure, as well as research and development in the technologies that will shape the future. As part of its push, the Indian government believes shifting towards AI will help fight poverty in a country where the one in four people live below the poverty line for developing countries.

India’s AI adoption is speeding up. India’s professional workforce already has one of the highest adoption rates in the world. A global workplace study by Emeritus last year found that 96% of Indian professionals used AI and generative AI tools at work, much higher than the 81% in the US and 84% in the United Kingdom.

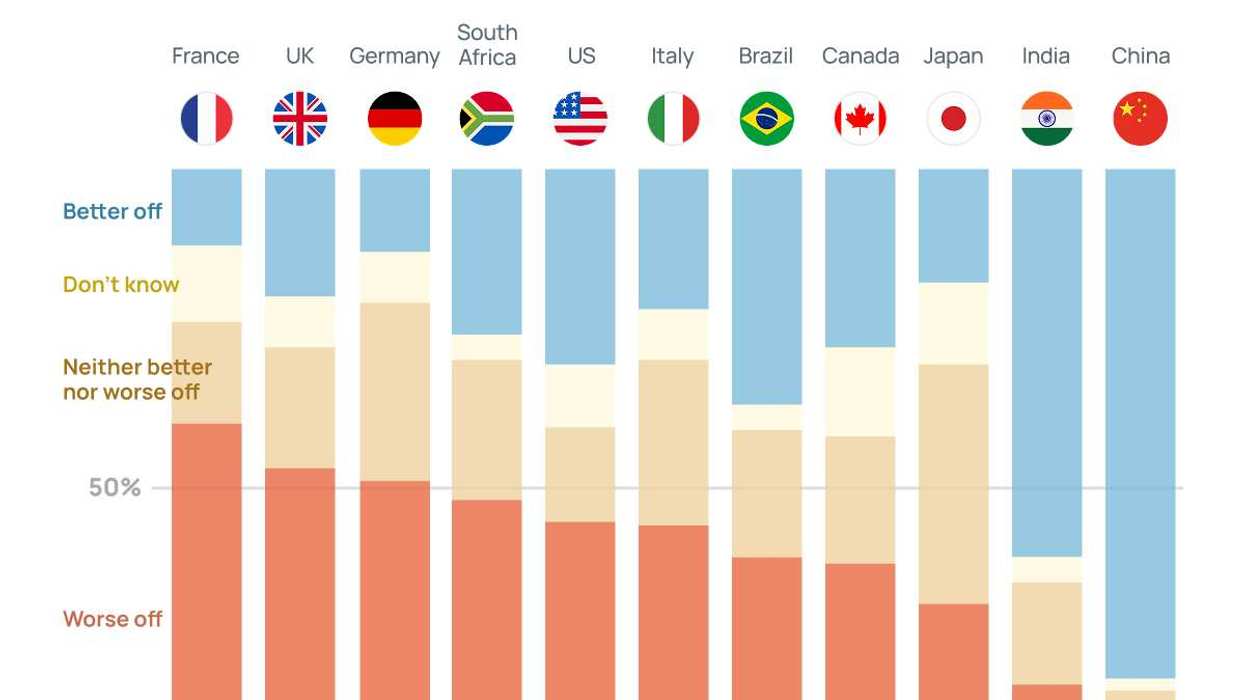

Public opinion appears to align with that view. Only 19% of Indians were more concerned than excited about AI, according to a Pew survey last year. That stands in sharp contrast to a number of G7 countries, particularly the United States, where 50% of Americans are pessimistic about the technology.

That contrast speaks to differing economic realities and approaches toward AI. In the US, for example, public polling shows that many fear that the technology will lead to massive job losses in white-collar and entry-level employment. Despite US President Donald Trump’s full-throttle push for AI research and development, polls show the majority of the American public believes the technology will shrink the number of jobs on the market. By contrast, India is home to the world’s fastest-growing major economy but has a large underemployed and rural population. There’s a rich pool of tech talent that stands to gain from AI development and a rural population that has yet to test much of it.

Optimism doesn’t translate to readiness, though. India’s AI development still lags far behind that of the US and China, and it is short on the resources needed – namely water, land, and stable electricity – for the data centers it hopes to build. Few countries can pour billions of dollars into creating frontier AI models – large scale systems like GPT-4, Claude, or DeepSeek – like the US and China. Those challenges seem to be symbolically on display at the summit this week, where logistical chaos – long lines and confusion over QR codes – overshadowed the opening day.

Still, Indian companies are building AI models that are cheaper to develop than ones in the US – like Adalat AI, a transcription tool for legal proceedings that’s fluent in India’s many languages. Organizers of this week’s AI summit are presenting the tool as an example of the kind of frugal, multilingual, and publicly-accessible technology it believes will position the country as the AI leader of the Global South.

India’s AI sovereignty push. Despite the desire for investment from American tech companies, India is wary of reliance on either the US or China. “It has a very hostile relationship with China and does not allow most Chinese platforms to operate in India,” explains Pramit Chaudhuri, South Asia expert at Eurasia Group. “While welcoming of Western investment, it is determined to develop its own sovereign AI capabilities.”

As a result, India is pushing to develop its own AI capacity that allows room for alternatives to US technology, part of a broader push for what policymakers, including in other countries like France, have dubbed “digital sovereignty.” The summit, for example, featured a new sovereign AI platform from an Indian startup called Sarvam AI, a voice-command model that the company says could evolve into India’s own large language model (LLM), software designed to understand and generate human-like text. That’s a space currently dominated by the US.

Is there a geopolitical opening? India is far from being a technological superpower, Chaudhuri explains. But there is a strategic opening. For years, the European Union has tried to use its clout as the largest advanced consumer market in the world to set global norms on privacy, content moderation, and now AI. Critics have argued this effort has hampered Europe’s competitiveness in the tech market. As a result, India sees an opening, or a “second-tier space,” as Chaudhuri calls it, below the US and China.

Whether India can fill that space – and translate its AI optimism into enduring capability – is worth watching. At a moment when the world’s once-in-a-generation technology is evolving, India is betting it can be not only a leader in the Global South and a consequential player in AI.