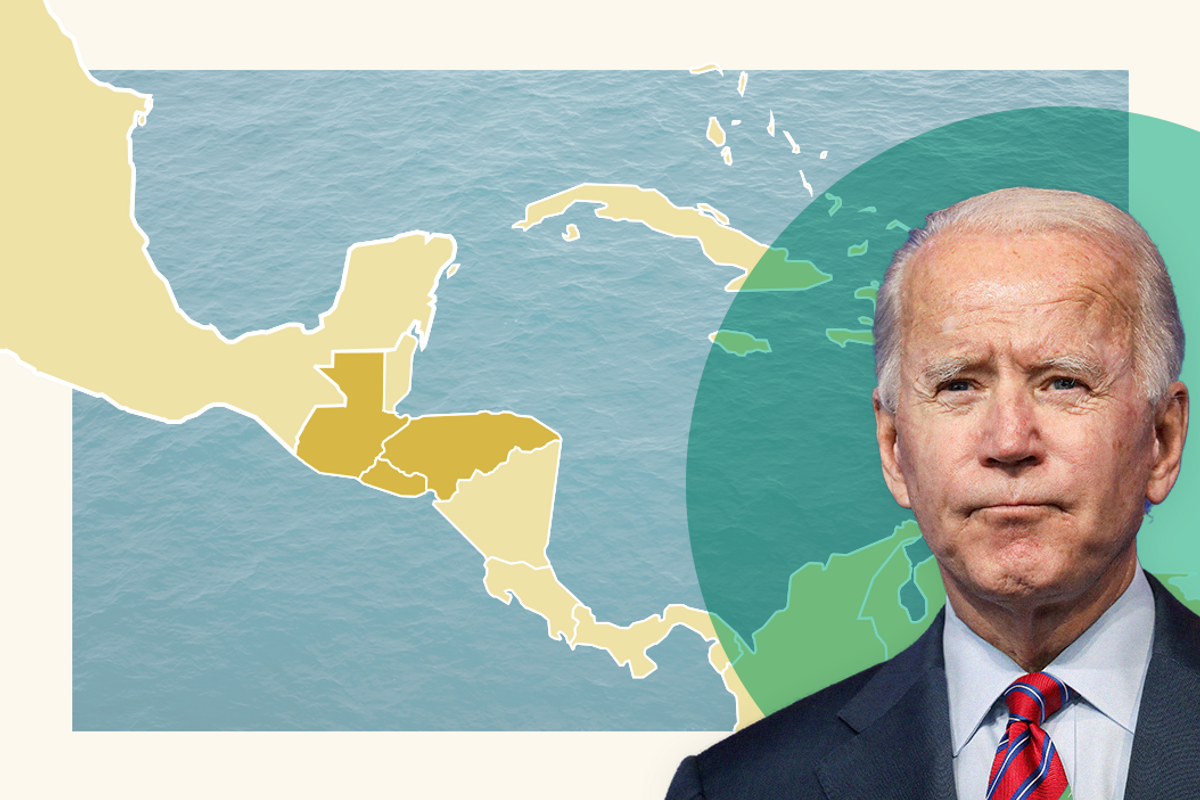

In recent months, large numbers of men, women, and children from the so-called Northern Triangle of Central America – Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador – have left their countries in hopes of applying for asylum in the United States. This wave of desperate people has created a crisis at the US border and a political headache for President Joe Biden. US border officials now face the highest number of migrants they've seen in 20 years.

Biden has a plan to manage this emergency. The idea is to invest $4 billion in these three countries over four years to help create the political and economic conditions that can make them more prosperous, and more secure. The goal is to persuade Honduras, Guatemalans, and Salvadorans that they and their children can thrive where they are.

The Triangle countries need the help. The people who live there have taken hits from poverty, crime, gang violence, drought, COVID-19, and two category 5 hurricanes in November 2020. In recent years, the US has directed money toward training and technical assistance to help farmers grow more food, the physical infrastructure needed to expand trade, and better nutrition for women, children, and babies. The difference this time is that Biden is offering much more money, nearly double the amount the US approved for these countries over the past four years.

But the Triangle countries have long been plagued with government corruption. In fact, earlier this week, Rep. Norma Torres (D-CA) published a State Department list of 16 public officials from these three countries that are subject to "credible information or allegations" of corrupt acts. The list includes current Honduran and Guatemalan lawmakers, a senior aide to El Salvador's president, and former state officials from all three governments. The accusations include financial crimes and drug trafficking.

How can the Biden plan produce the broad benefits Washington hopes will stabilize these countries if state officials steal a lot of the money? The text of the plan offers several answers. To receive US help, the governments of these countries must "allocate a substantial amount of their own resources and undertake significant, concrete, and verifiable reforms," show "verifiable progress to ensure that U.S. taxpayer funds are used effectively," and "combat corruption." The Biden plan also directs some of the investment into "civil society organizations that are on the frontlines of addressing root causes" Lending from the International Monetary Fund comes with similar strings attached.

Yet, the Triangle governments have other financial options. El Salvador's President Nayib Bukele dismissed the latest corruption allegations from Washington as "geopolitics," and thanked China for providing his country with 500,000 doses of a Chinese-made COVID vaccines and $500 million in investment "without conditions."

Bukele may be inflating the size of that investment, and his comments are partly political bravado and negotiating strategy. But later that evening, El Salvador's Congress ratified a deal with China, signed in 2019 after the Salvadoran government dropped diplomatic recognition of Taiwan, that would invest about $62 million in port infrastructure along El Salvador's coast, a water purification plant, a library, and a soccer stadium.

Honduras and Guatemala don't yet have formal ties with China, but that might change soon.

So, there's the Biden dilemma. You can't ease the flow of desperate people toward the border without investing in better economic conditions in the Northern Triangle. You can't be sure your investments will reach their target without political reforms that reduce corruption. You can't always use money to try to force these governments to reform when they can turn to China and other sources for investment.

On the other hand, isn't Chinese infrastructure investment in these countries a good thing? Maybe Washington can get the development and stability it wants in Central America without having to spend so many US taxpayer dollars to get it. The true answer to this question depends, of course, on what China chooses to invest in.

What do you think, Signal readers? What's the most effective way to solve this dilemma? Let us know.