On August 30, right before the clock hit midnight in Kabul, a C-17 cargo plane carrying the last US service member in Afghanistan got off the ground, thus ending America's longest-ever war.

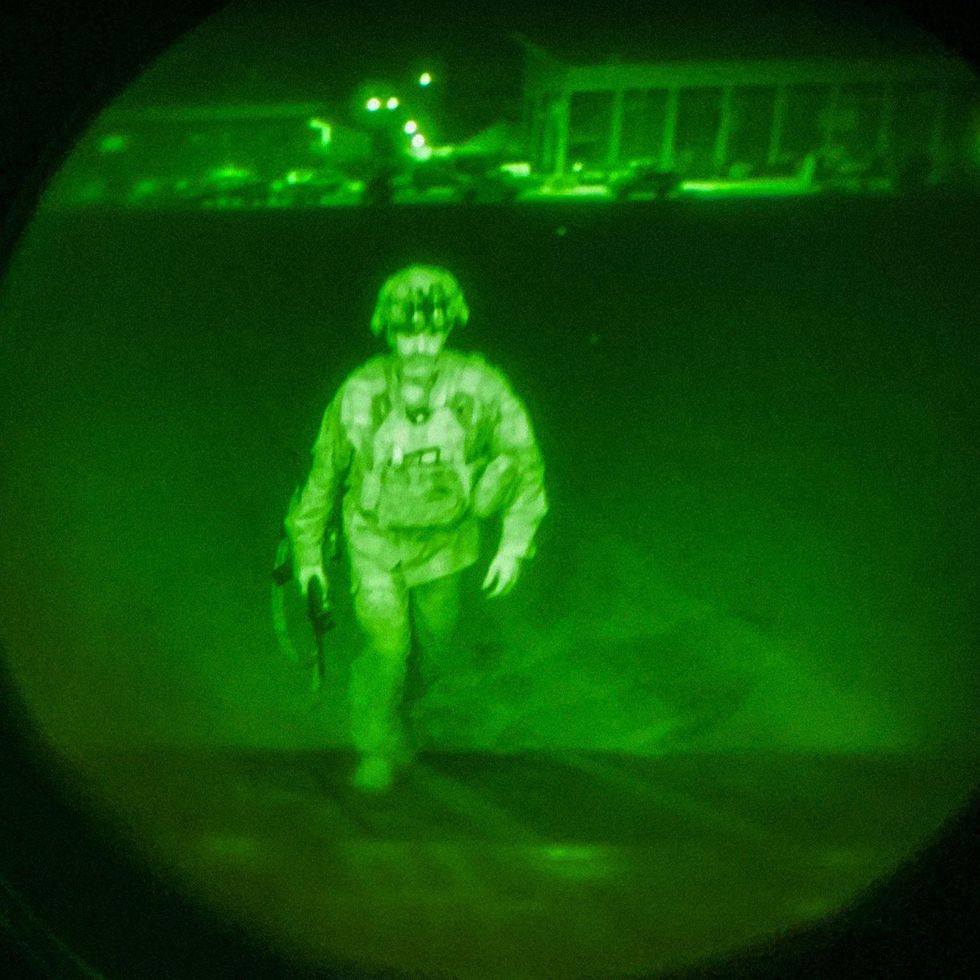

The last American soldier, Maj. Gen. Chris Donahue, boards a C-17 plane in Kabul. (US Central Command)

The last American soldier, Maj. Gen. Chris Donahue, boards a C-17 plane in Kabul. (US Central Command)

Here's everything you need to know (but were afraid to ask) about how we got here, what it means both at home and abroad, and what to watch for in the coming weeks and months.

Post-mortem of a tragedy foretold

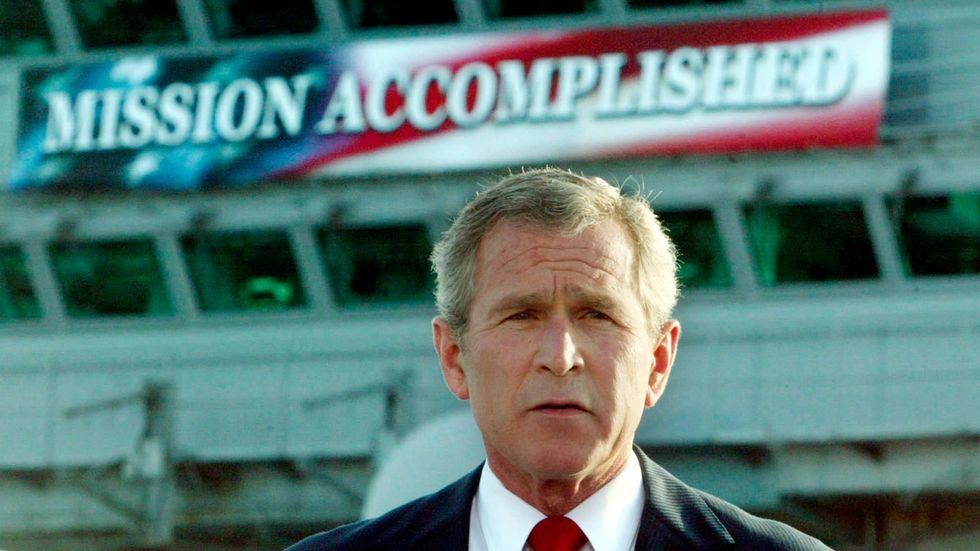

Did the US lose the Afghanistan War? War is a means to an end, so the answer depends on what you think the mission was. If you believe, as the American people were told right after 9/11, that the goal of invading Afghanistan was to annihilate al-Qaeda and prevent those in the country from directly threatening the United States, then mission accomplished. As I wrote recently and Joe Biden said on August 31, "We succeeded in what we set out to do in Afghanistan over a decade ago." However, if you believe the mission was (or should've been) to help Afghanistan build a stable and sustainable government, and ensure it would no longerserve as a crucible of Islamic extremism, the US clearly failed.

Want to understand the world a little better? Subscribe to GZERO Daily by Ian Bremmer for free and get new posts delivered to your inbox every week.

President George W. Bush delivering a speech to crew aboard the USS Abraham Lincoln in May 2003.(Larry Downing/Reuters)

President George W. Bush delivering a speech to crew aboard the USS Abraham Lincoln in May 2003.(Larry Downing/Reuters)

Was Biden right to withdraw? Like most policy questions, this one is debatable, but my answer is Yes. Trump, Biden, and most Americans agree: nation-building Afghanistan is far from the most important problem facing the US (and, even if you disagree, you wouldn’t go about it by repeating the mistakes of Vietnam…). Ever since Bin Laden was killed in 2011, public support for the war tanked. The Taliban had been gaining strength since Obama's second term so the status quo was not sustainable without a massive surge in troops, but "If 20 years and $2 trillion couldn’t buy self-sustaining stability [for Afghanistan], no amount of additional time would […] The only alternative to withdrawal, committing more troops and money, had no political buy-in." In a democracy like the US, withdrawal was a no-brainer. Read more➔

Could the US have won the war with a small but indefinite presence? No. True, the US footprint was relatively small at the end and there had been no US casualties since early 2020, but this was a direct result of President Trump's ceasefire agreement with the Taliban—which was predicated on the US getting the hell out of Dodge. Meanwhile, Afghan defense forces were losing lives and territory to an emboldened and stronger-than-ever Taliban. Had Biden reneged on Trump's commitment to withdraw, the Taliban would have intensified its attacks against the outnumbered Americans. Staying indefinitely with ~2,500 boots on the ground was not an option. As Biden said on August 31, the only choice was "between leaving and escalating."

Why did the country collapse so quickly? Biden claims that the evacuation could not possibly have been done "in a more orderly manner." I disagree. There were four key failures in the execution of the withdrawal: (1) a military and intelligence failure, (2) a coordination failure, (3) a planning failure, and (4) a communications failure.

Why did the US shun its allies? There were five key reasons: (1) bad intelligence, (2) centralized decision-making, (3) domestic politics, (4) belief that the damage had already been done, and (5) pandemic communication challenges.

What does it mean for US adversaries? Despite glib gloating about America's humiliating retreat, the power vacuum left by the US creates big headaches for its foes. China, Russia and Iran may not have liked the American-backed Afghan government and are surely happy to see the US look inept, but they’ll like instability in their backyards even less. Neither country wants an eruption of violence in Afghanistan that could spill over to their borders and lead to refugee waves, increased risk of terrorism, and economic disruption. They will engage with the Taliban but remain wary of its checkered past, and are unlikely to invest significantly in the country until the new government shows that it is able and willing to maintain order and safeguard their interests. Watch more➔

What's next

Is the war over for Afghan civilians? Far from it. While the US has called it quits, regular Afghans are now facing the prospect of a prolonged civil war. And as Afghan teacher and human rights activist Pashtana Durrani told me, the war won't be over until there is "peace and progress." It's just a different type of war now: a war for rights, for children, for women, for education. But not all is lost. As Afghan-American rights advocate and former US and UN official Rina Amiri put it, while progress will be more gradual and clandestine than it'd been in the last 20 years, activists "will find a way."

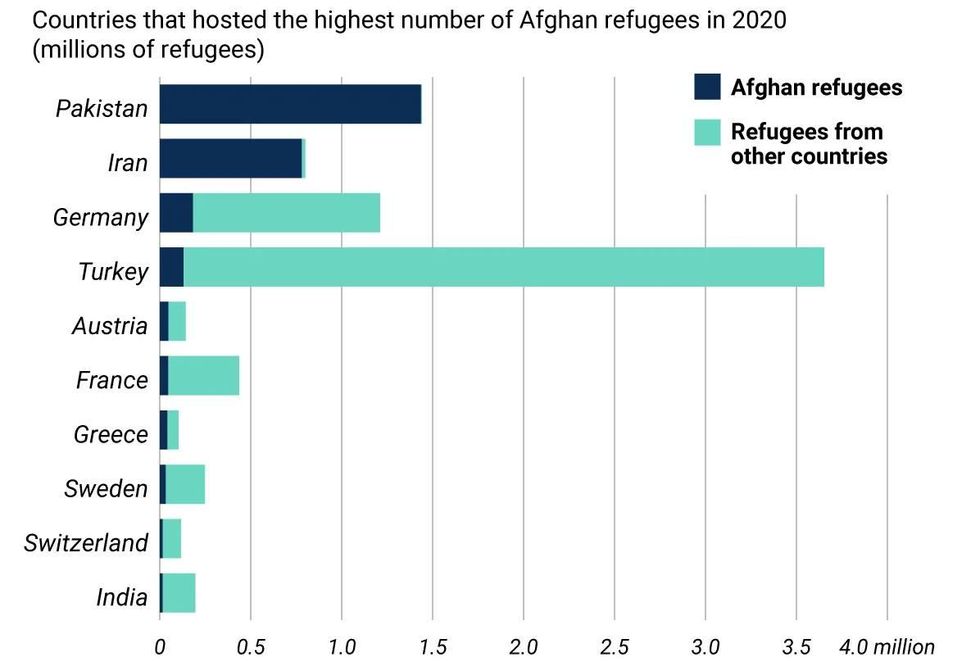

What will happen to Afghan refugees? As my GZERO colleagues have written, “Most will likely try to head to Europe, but few countries anywhere along that route seem willing to take them in.” That includes not just attractive destination countries like Germany, which is wary of a repeat of the 2015 Syrian refugee crisis that destabilized European politics (especially in the run-up to elections), but also neighboring Iran and transit hubs Turkey and Greece. The US will welcome a negligible number of Special Immigrant Visa (SIV) holders and even fewer asylum seekers. Rory Stewart, ex UK international development chief, thinks "the fundamental problem is not the Taliban letting people out," but rather "other countries letting Afghans in." The unfortunate truth is that many Afghans in danger may not have a way out. Read more➔

What will happen to the Afghan economy? As my GZERO colleagues have pointed out, while the Taliban were able to take the country at gunpoint, they will need loads of money to make the government run, and illegal cash flows from drug trafficking, extortion, and mining can only take them so far. The economic outlook for Afghanistan is dire, according to former central bank chief Ajmal Ahmady. Most foreign-currency assets have been frozen, foreign aid flows have dried up, the currency has depreciated sharply, and inflation has shot up. In an interview for an upcoming episode of GZERO World, Ahmady told me that a full-blown financial crisis is imminent. Soon enough, he thinks, the Taliban will be “forced to cut expenses [and services] significantly,” and regular Afghans will pay the price. The Taliban may hope that China will step in to make up the difference in international financing, but Ahmady is skeptical that any significant investments will materialize on the timeframe and scale needed to avert humanitarian catastrophe. Watch more➔

Will the Taliban behave better than they did the last time they were in power? While they may be saying the right things and playing nice for the cameras in Kabul, Afghans aren't buying it, and neither should we. Afghan teacher and activist Pashtana Durrani told me that “What they’re promising and what they’re doing are two different things.” Ajmal Ahmady, former Afghan central bank chief, agrees, saying "there's little reason to believe [their promises]," given not just their record but the fact that they're still reportedly knocking on doors and kidnapping activists and former government officials. Rina Amiri, an Afghan-American women rights advocate and former US and UN official, shared similar stories from activists on the ground, who report seeing "not a rehabilitated Taliban, but a more brutal and systematic Taliban."

How will the Taliban govern? Taking over a country and ruling it are two very different things. Afghan teacher and activist Pashtana Durrani told me the Taliban did not come in with a plan to govern. “Military men can never do public policy,” she said. Ex central bank chief Ajmal Ahmady reckons that the Taliban themselves are “trying to figure it out” on the go. In the meantime, public offices are paralyzed and technocrats are being and replaced by fighters. What is certain is that any semblance of electoral democracy is out of the question, and Sharia will be the law of the land. But unlike last time, the Taliban now seem intent to gain international legitimacy and make allies in the hopes of making their hold on power more sustainable. Does this mean they will rule in a less totalitarian and extreme fashion? TBD, but Afghan-American policy expert Rina Amiri is not holding her breath. Read more➔

Who will keep the peace in Afghanistan? The most obvious answer is the Taliban, but last week’s suicide attacks by ISIS-K “have sown fresh doubts about the Taliban's capacity to maintain even basic security once the US is gone.” The US will want to stay in the loop to prevent the country from becoming a terrorist launching pad, but without boots on the ground, it’ll need to rely on mutual self-interest from its adversaries China, Iran and Russia, frenemies like Pakistan, and NATO allies Turkey and Qatar. All these countries have a vested interest in ensuring a stable Afghanistan. Read more➔

🔔 And if you haven't already, don't forget to subscribe to my free newsletter, GZERO Daily by Ian Bremmer, to get new posts delivered to your inbox.