I get asked all the time whether the 21st century will be an American century or a Chinese century. What if the answer is ‘neither’?

Nation states have been the primary drivers of global affairs for nearly 400 years, in charge of conducting war and peace, providing public goods, writing and enforcing laws, and controlling flows of information, goods, services, and people. The Peace of Westphalia signed in 1648 enshrined territorial sovereignty as the basis of international relations, a system that has reigned supreme since.

But times are changing. As I explain in a newly published article in Foreign Affairs titled “The Technopolar Moment: How Digital Powers Will Reshape the Global Order,” the creation of the Internet is bringing a change in the global order that could make the Westphalian state system a thing of the past.

Want to understand the world a little better? Subscribe to GZERO Daily by Ian Bremmer for free and get new posts delivered to your inbox every week.

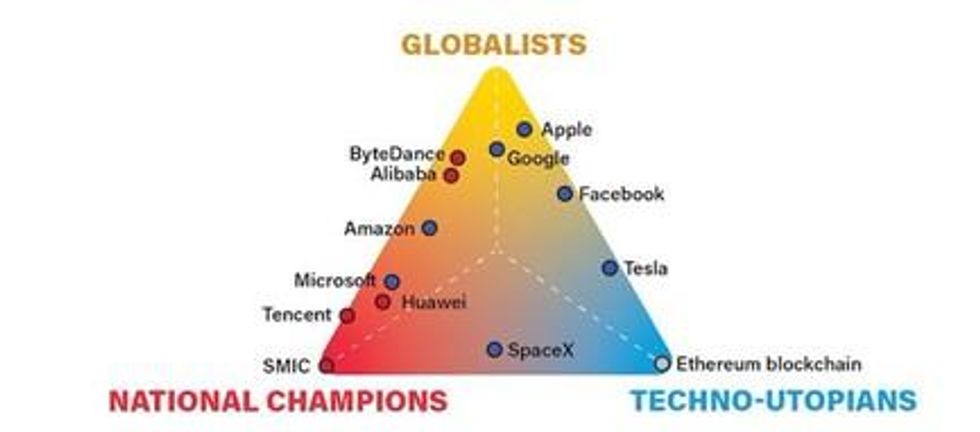

The gist of the argument is that a handful of very large technology companies have amassed enough power to wrest control over societies, economies, and even national security away from states. Increasingly, these companies are behaving not just as companies but as sovereigns, in direct competition for geopolitical influence with states.

Want proof? Look at what happened in the immediate aftermath of the January 6 insurrection. Congress and the judiciary were powerless to respond. Law enforcement did so late, sparingly, and only thanks to their use of social media to identify individual offenders. Contrast the state’s absence with Big Tech. Facebook and Twitter swiftly de-platformed President Trump. So did Paypal, Stripe and Shopify. Amazon, Apple and Google banished Parler, the social network rioters used to organize the Capitol mutiny. These companies did all this of their own volition.

Tech companies were able to exert this power because they own and control a growing share of the infrastructure that societies, economies, and governments worldwide increasingly run on. They have, in other words, sovereignty over a realm where nation states have limited power: cyberspace. This means that when it comes to geopolitics, states are no longer the only game in town. Tech giants’ sovereignty over digital space makes them geopolitical actors in their own right.

What’s so special about Big Tech, you might ask? After all, they aren’t the first private actors in history to shape policy. Corporations like the East India Company, Exxon, and IG Farben wielded tremendous geopolitical influence, as did the likes of Andrew Carnegie, Henry Ford, and J. P. Morgan. But even these legendary companies and robber barons ultimately operated in physical space and through governments, which always remained—at least nominally—in the driver’s seat even in those times when policy was captured.

Big Tech is different. Unlike the multinational corporations of yore, these companies are able to drive geopolitics in the digital world—a space they created, whose rules of the road they design, and where an ever-growing share of civic, economic, and private life is taking place. Their algorithms shape what information people see, believe, and act upon. Tech companies control not only the space where citizens increasingly spend their time, but also how they behave and interact with one another.

Even governments’ ability to serve their citizens increasingly relies on Big Tech. That’s because tech giants are responsible for providing an ever-growing share of the goods and services needed to operate a modern society. We’re talking telecommunication networks, cloud infrastructure, logistics capabilities, payment systems, space exploration, and, increasingly, national security. As I wrote in the article, “[w]hen Russian hackers breached U.S. government agencies and private companies last year, it was Microsoft, not the National Security Agency or U.S. Cyber Command, that first discovered and cut off the intruders.”

Source: pic.twitter.com/Gg57HXCsBZ

— Marcelo P. Lima (@MarceloPLima) September 25, 2021

Of course, how these companies are ultimately able to shape geopolitics also depend on how different governments respond to their growing reach. Indeed, Big Tech’s takeover of the role of nation states is to some extent a policy choice. After all, corporations are state creations, figments of the legal, regulatory, and monetary frameworks only modern states provide. While cyberspace is virtual, the servers, data centers, money, and people it runs on are physical entities, located in territories controlled by states, subject to national laws enforced by state powers. This means that states do have levers to rein in Big Tech.

Whether they are able and willing to use them is a different matter, one that varies according to each country’s capabilities, constraints, and politics. Either way, it’s too soon to mourn the death of the nation state. I, for one, seriously doubt they will go gently into the good night.

The future of the world will be most shaped by:

— ian bremmer (@ianbremmer) October 20, 2021

What is certain is that no matter the final power-sharing outcome, the very competition for dominance between and among states and tech companies will have significant implications for the future of the world.

🔔 And if you haven't already, don't forget to subscribe to my free newsletter, GZERO World with Ian Bremmer, to get new posts delivered to your inbox.