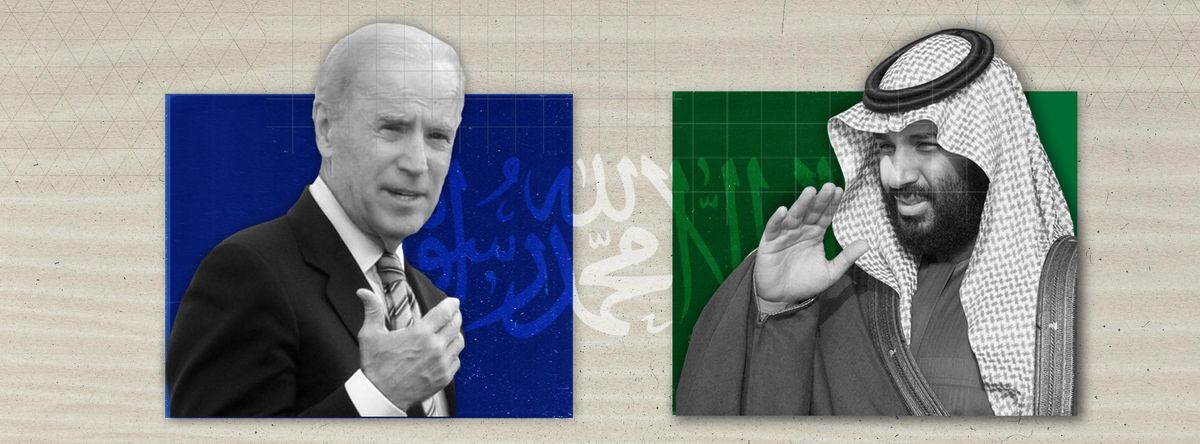

U.S. President Biden arrived in Saudi Arabia today as part of his first trip to the Middle East as president, a four-day regional tour that also included stops in Israel and the West Bank. While in Saudi Arabia, Biden is meeting with King Salman and Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, in addition to the leaders of the Gulf Cooperation Council countries and those of Jordan, Egypt, and Iraq.

But it is his encounter with ‘MBS,’ as the Saudi crown prince and de facto ruler is known, that has sparked the most controversy. You will remember that during the 2020 presidential campaign Biden vowed to make MBS a “pariah,” largely in response to the 2018 brutal murder of dissident Saudi journalist and American resident Jamal Khashoggi. The U.S. intelligence community found the crown prince was directly responsible for ordering the killing.

For an administration that claims to put “human rights at the center of American foreign policy,” the kingdom’s atrocious human rights record, its involvement in the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks, and its role in Yemen’s bloody and ongoing civil war made it an uncomfortable friend to have.

U.S.-Saudi relations had been accordingly strained since Biden took office. His administration released the intelligence community’s report on Khashoggi’s murder, issued sanctions and visa bans on Saudi officials, declassified documents from the 9/11 investigation into Saudi involvement, removed the terrorism designation of Yemen’s Houthi rebels, and halted all offensive arm sales to Saudi Arabia. And, in keeping with his promise to isolate MBS, Biden himself refused any direct engagement with the crown prince.

Until now.

Want to understand the world a little better? Subscribe to GZERO Daily by Ian Bremmer for free and get new posts delivered to your inbox every week.

After months of foot-dragging and internal debate, Biden decided to reverse his position. At a time when Russia is at war with the West, energy prices are sky-high (but declining), inflation is soaring, Iran nuclear talks are faltering, and competition with China is ramping up, the president’s advisors convinced him that shunning Saudi Arabia is not in the U.S. interest.

Critics argue that the about-face flouts Biden’s stated commitment to human rights in exchange for the promise of cheaper gas—an immoral and cynical trade, in their view. For its part, the White House has sought to downplay the role of energy, instead framing the visit around great power competition and regional security.

Biden preemptively defended a reset of the relationship in an op-ed for the Washington Post, saying “it will advance important American interests.”

"As president, it is my job to keep our country strong and secure. We have to counter Russia's aggression, put ourselves in the best possible position to outcompete China, and work for greater stability in a consequential region of the world," Biden wrote.

"To do these things, we have to engage directly with countries that can impact those outcomes. Saudi Arabia is one of them, and when I meet with Saudi leaders on Friday, my aim will be to strengthen a strategic partnership going forward that's based on mutual interests and responsibilities, while also holding true to fundamental American values," he added.

I think Biden is right.

He should be going to the Middle East, and if he’s going to the Middle East, he should be going to Saudi Arabia. Not first and foremost because as the world’s top oil exporters, the Saudis can help lower U.S. energy costs—they can’t, they won’t, and they don’t need to because they are coming down on their own—but because of everything else a healthy U.S.-Saudi relationship does to advance America’s strategic interests.

The kingdom has been a valuable partner of the U.S. since the 1940s. It is America’s largest arms purchaser and the most aligned with the U.S. on regional security and opposition to Iran, providing vital intelligence and counterterrorism cooperation. As Russia and—more importantly—China look to grow their influence in the region, keeping Saudi Arabia firmly in America’s camp makes good strategic sense.

To be sure, the kingdom’s actions—including not just the Khashoggi killing, domestic repression, and other human rights abuses but also the blockade of Qatar, the war in Yemen, the fence-sitting and hedging on Russia and China—have often been out of step with American interests and values. But as the administration recognizes, Saudi Arabia’s behavior has become more constructive.

Under MBS and his increasingly competent and meritocratic cabinet, the kingdom has undertaken meaningful and overdue social and economic reforms enhancing the role of women, diversifying the economy away from oil, downgrading the role of religious law, and generally making the country more open, tolerant, and investable.

On the regional front, MBS lifted the blockade on Qatar, which houses the largest U.S. military base in the Middle East, and has helped to restore unity among the Gulf Cooperation Council countries, making it a more effective counterweight to Iran. The Saudis have also been working increasingly closely behind the scenes with Israel, America’s closest ally in the region, and have blessed the ongoing normalization of relations between the Jewish state and the Arab world. And in Yemen, where a Saudi-led coalition has been fighting Iran-backed Houthi rebels for eight years, engendering one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises, the crown prince has embraced a ceasefire that continues to hold after three months.

None of these signs of moderation indicate that the kingdom has suddenly become Scandinavian in terms of human rights, nor do they suggest U.S. and Saudi interests are now perfectly aligned. It hasn’t and they aren’t.

Biden still mistrusts MBS, who he considers a “thug.” The two countries continue to have fundamental differences on democracy, human rights, and climate change. To Washington’s chagrin, commercial and strategic interests will keep driving Riyadh closer to Beijing and, to a lesser extent, Moscow. The Saudis aren’t about to kick Russia out of OPEC+, rebuff Chinese overtures, or formally normalize relations with Israel. Most importantly, they are unlikely to do much to lower U.S. gas prices ahead of November’s midterm elections—both because they have limited spare capacity to increase oil production and because they don’t see a supply shortage given the softening demand outlook. (Even if they did pump more crude, it would only have a marginal impact on prices at the pump due to the U.S.’s limited refining capacity.)

But the kingdom’s recent policy shifts do go in the right direction. Along with Saudi Arabia’s enduring—and largely structural—strategic value to the U.S., they merit a change in the administration’s posture toward Riyadh.

The United States has the ability to engage with Saudi Arabia on areas that advance its interests at the same time as it opposes some of the kingdom’s policies. What it can’t afford to do is let high-minded values dictate its foreign policy, especially given America’s own failure to live up to said values both at home and abroad.

By traveling to Saudi Arabia, President Biden is putting the national interest ahead of his conscience and his political interest. That’s a hard, laudable, and increasingly rare choice in modern politics. The path of least resistance would have been to stay the course and continue isolating the crown prince. That strategy might have been good politics, but it was never going to succeed. After all, MBS is only 36 years old. He is likely to rule the kingdom for decades to come. Sooner or later, engagement with him was inevitable.

If anything, the president’s mistake is not to make the trip—it was to promise to “center” Saudi policy on democracy and human rights. That was never a credible pledge to begin with.

🔔 And if you haven't already, don't forget to subscribe to my free newsletter, GZERO Daily by Ian Bremmer, to get new posts delivered to your inbox.