The conventional wisdom is that Russia’s war in Ukraine has settled into a slow grind as Russian forces gain territory acre-by-acre across the Donbas region. But behind the war’s slow-rolling violence, three frantic races are well underway.

Russia’s race

Russians continue to outgun Ukrainian forces, but they face an urgent shortage of manpower to successfully absorb the blow that a coming large-scale Ukrainian counterattack will likely deliver. Putin has proven reluctant to draft large numbers of Russian civilians into the army, but his government is now scrambling to enlist every available soldier by offering eye-catching salaries and raising the age of eligibility from 40 to 65.

There is also some evidence that Russia is trying to conscript large numbers of troops from within the Ukrainian territory they occupy. All these new soldiers must be trained as quickly as possible.

Russians are also digging in, both militarily and politically, to hold the Ukrainian territory they’ve already captured. That means building defenses that can withstand heavy bombardment and setting up administrations in occupied territories to stage political referendums on independence or annexation by Russia.

Ukraine’s race

Ukrainian forces, now in slow retreat, badly need to launch that large-scale counteroffensive against Russia’s advancing army in the next few months. If they can’t reverse Russia’s momentum by November, Kyiv runs the risk that US and European allies will become reluctant to help and that Ukraine’s economy will collapse.

A successful counterattack will require many more precision-guided Western weapons capable of striking strategic targets that support Russia’s advance, extensive training for how to use those weapons, and large amounts of cash to save Ukraine from economic collapse. They need all these things yesterday.

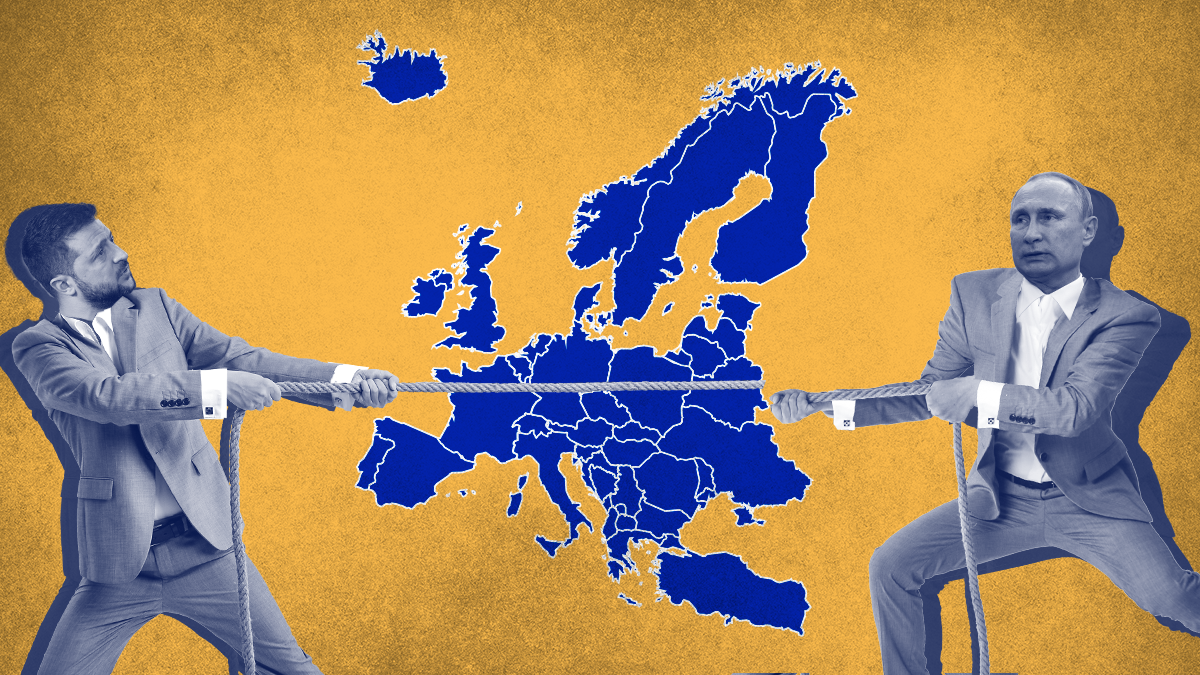

Europe’s race

Part of Ukraine’s urgency comes from warnings that Europeans must race to prepare for a winter in which Russian energy won’t be available to heat homes or power industry. In particular, Germany, with Europe’s largest economy and a still-deep dependence on Russian natural gas, faces some tough choices.

“If Russia suddenly cuts nearly all its natural gas exports to Germany,” warns Eurasia Group’s Naz Masraff, “Berlin may struggle to cope with high heating demand next winter, potentially forcing Berlin to ration supply to some industries and take actions that inflict pain on consumers.”

That fear is real. Gazprom, Russia’s state-owned gas supplier, reduced gas flows to Germany by 60% in June. The company blamed technical problems, but the German government (rightly) sees this as a muscle flex from Vladimir Putin and a reminder that Europe can’t control the pace of its plans to halt imports of Russian energy.

Germany’s government has added new urgency to secure gas supplies from other sources and fill storage facilities. It’s also ramping up coal-fired power generation while asking industry and consumers to use much less energy. There is also debate about whether to extend the lives of Germany’s three remaining nuclear reactors, which are scheduled to close at the end of this year.

The big picture

The outcome of these three races will decide what the map of Ukraine looks like when Russian and Ukrainian officials finally sit down for the serious negotiations needed to end the war.

That day isn’t close, because both sides still believe they can win, though victory remains undefined in both Moscow and Kyiv. But Russia wants to gain more ground and force the US and Europe to hedge their bets on Ukraine’s future. Ukraine wants to deal Putin’s power a heavy blow and ensure that Western backing has staying power.

The clock is ticking down to the moment that winter changes the game.