f you follow me outside of my Bulletin newsletter, you know that I do my best to talk to the public regularly about the geopolitical stories of the day. But a 5-minute cable news hit is too short to convey the subtleties that really matter.

That’s why I have my own TV show and podcast, GZERO World with Ian Bremmer, where I get to spend 30 minutes each week diving deep on the issues I think are important. It’s also why I love doing long-form interviews with solid analytical journalists.

So when my fellow Bulletin writer Jessica Yellin asked to interview me about the Russia/Ukraine situation, naturally I jumped at the opportunity.

For those of you who don’t know her, Jessica is an award-winning political journalist who reported for ABC, MSNBC, and CNN (where she was chief White House correspondent) before starting her own digital news platform, #NewsNotNoise. Much like my media company GZERO Media, NNN breaks down the biggest stories and separates news from noise.

I went on Jessica’s podcast this week to discuss the crisis brewing in Ukraine and was deeply impressed by her incisiveness. We covered a lot of ground, so only part of our conversation is excerpted here (lightly edited for clarity). Jessica’s questions are in bold.

Want to understand the world a little better? Subscribe to GZERO Daily by Ian Bremmer for free and get new posts delivered to your inbox every week.

Listen to the full podcast episode here.

What has Russia been up to in recent weeks that has the US so convinced that Putin is planning for an invasion?

It seems to be a combination of things. You have the 130,000 Russian troops amassed along Ukrainian borders. The Russians are about to begin major exercises in the ostensibly independent neighboring state of Belarus, which will also increase their capability to invade Ukraine. They have engaged in cyberattacks against Ukraine in the last couple weeks with some pretty significant warnings on computer screens saying more is coming. And they've expressed a fair level of urgency on the diplomatic side that this needs to be addressed now, or else they're going to take some measures, even though the Russian foreign minister says they don't want war. But as Tolstoy once said, “You may not want war, but war may want you.” So there are reasons why the Americans are concerned.

I will tell you the intelligence community in the United States is convinced that a full-scale invasion is coming and I don't buy it. But they're not just convinced on the basis of the data they're sharing. They're clearly convinced on the basis of some intelligence that they have. And I think Biden has been raising more alarm bells in recent days on the back of those briefings.

You are one of the few analysts who believes that a diplomatic solution is still possible. What in your mind might pacify Putin? What could the West give him short of barring Ukraine from NATO that would let him back down and save face?

Well, I don't think he necessarily has to back down. In other words, the media has been sort of bipolar on this, saying that either diplomacy works or we're going to war. And I just don't think those are Putin's options.

I think Putin has an awful lot of range in between those two dots that allows him to take a few bites of the apple and see what happens. See if the Americans and NATO are still as aligned, see if the Ukrainians get skittish and want to negotiate. There are plenty of things short of an invasion that the Russians can do that make it harder for the Americans to maintain a united front with all of their allies, and if I were advising Putin, I would tell him to at least try. And negotiations, both with the United States in a bilateral format but also with the Europeans and Ukraine in the so-called Normandy format, can be going on at the same time. I believe that it is possible that there's a deal to be cut in the midst of all of that between the West and Russia. I know it doesn't really feel like that because the drums have been beating louder and louder for weeks now, but we're still early days in this conflict.

Again, I accept that a full-on invasion is possible. But you need to think about what the consequences would be for President Putin going forward if he were to take some of these more significant steps. And there, I really do believe, a full-on invasion is strongly not in his interest. It would be costly economically. It would be very unpopular domestically, and, and perhaps most importantly, there is nothing he could do that would be more effective in reunifying and reinvigorating and creating a new mission for NATO. And that mission would be to defend against Russia. And that's clearly the antithesis of what Putin is interested in. And I've always believed that stupidity is not an interesting analytic category. So when you go through and do the analysis and you realize something is absolutely insane, you tend to discount that as an option.

If Putin does move forward with an invasion, what's the timeframe in your view?

I think late February is the most likely timeframe for that. Certainly it would not come until the Beijing Olympics were over, because China is such an increasingly critical ally of the Russian government. And they don't have many friends around the world, certainly almost no friends that matter. And an attack would not only undermine Russia's ability to keep the Chinese on side, but it would also distract massively from this most important thing that Xi Jinping is in charge of running, and he would be angry about that. So there's no reason for Putin to act beforehand. Furthermore, the Russia-Belarus joint military activities, which are unprecedented in scale, are planned to conclude coincident with the closing ceremonies of the Beijing Olympics. I'm sure nothing was meant by that, but it's an interesting data point.

Let's discuss the why. What's Russia's strategic interest in Ukraine today and also what does Ukraine stand for historically for Putin in the context of the USSR?

As Putin would say, it's not Ukraine, it's My-kraine. The fact is that Russia has historically seen Ukraine as their territory, not as sovereign or independent. This goes back to the days of the czars. When the Soviet Union collapsed, you had famous Russian dissidents like Sakharov talking about how Russia definitely had to keep Belarus, Ukraine, and Northern Kazakhstan, because it was inconceivable that you could have Russia without them. You could lose the Baltic states. They had nothing to do with Russia. Historically, you could lose Uzbekistan. But you wouldn't lose Ukraine. Also, Putin considers the collapse of the Soviet Union the worst geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century. And he’s said that many, many times, both domestically and to foreign interlocutors. So I do think that this has a very different perspective if you're looking at it through a Russian lens rather than as Americans or Europeans, who think these countries of course all are independent.

Furthermore, if we go back to 2014, you'll remember that there was a former Ukrainian president that was forced out of power. The Americans together with the Germans and Poles meet with the Russians and come out with this quadrilateral agreement that we're going to have a unity government for a few months, and then there's going to be a new constitution weakening the president, and that keeps everyone happy. It makes Ukraine functionally kind of a buffer state. But that doesn't happen. On the ground, the Ukrainian opposition forces Yanukovych out, and a new pro-democracy pro-Western regime comes in. We weren't behind that, but we were perfectly happy to see it happen. The Russians assumed that George Soros and the CIA were involved and were part of the whole coup. The point is that we won, the Russians lost, and we kind of rubbed their noses in it after we had a deal, so they're angry about that. And this has never been resolved.

You have a Ukrainian president today, Zelensky, who has no business being president. He was a comedian in Ukraine that played the president in a popular local Ukrainian TV show. He was elected, very popular, very charismatic, but has no business running a country. When he first came in, Putin thought that he would be a pragmatic leader that the Russians could work with. It became very evident very quickly that was not the case. And indeed, over the last year, even though no one wants Ukraine in NATO, NATO's working much more closely with the Ukrainians and they're sending them more weapons. A lot of Turkish drones, for example, have gone over there. There've been more joint exercises, more training on the ground, all of which makes Ukraine look from the Russian perspective like a threshold NATO power and that's unacceptable to the Russian government. So they do have a number of grievances on Ukraine, some of which are legitimate.

How would you characterize Russian public support for any activity in Ukraine, but especially some sort of military invasion? Does Putin have backing?

The entire media complex in Russia is completely oriented to the state. What Russians hear is that the Americans and the Ukrainians are pushing for war and that they're committing acts of genocide against Russian nationals on the ground. If they hear that enough, they're going to blame the West for it. Of course they wouldn't support the war as we'll be reporting the war, but would they support the war as Putin ends up fighting and reporting the war to the Russians? Yeah, at least for a while. Now, when body bags start coming back over the course of 3, 5, 10 years, it'll become very deeply unpopular, but at least in terms of the way it is presented to the Russian people in the early days, they are on board.

I am surprised that the president of Ukraine, Zelensky, is saying that he doesn't think that Russia is on the cusp of invading their country, even though he has these troops on the border. You’d think a leader would be worried, but he's saying that the West is causing undue panic. What's motivating him? Is this disinformation? What's his view of Putin?

I understand why that's confusing. There are three different things going on.

First, what Zelensky is saying privately to the NATO allies in Europe is much more alarmist than what he is saying publicly. He's saying, “You guys have to send me as much military equipment as you possibly can. I need this right now, 5,000 helmets from Germany isn't going to cut it, look at what I'm facing on my border.” So, first of all, this is talking out of two sides of his mouth.

Second, if he talks about war, his economy collapses, right? The money leaves, the banks fall, the financial outflows are a problem. So he is trying to prevent that, he knows that an attack isn’t imminent and doesn't want to panic the population unnecessarily.

But then there's another point, which is he's trying publicly to squeeze the West into giving him more in terms of NATO. He doesn't want to be the sacrificial lamb in a deal cut between Russia and the United States that says Ukraine isn’t going to become a member of NATO any time soon. I think it is very possible that Western leaders would pressure the Ukrainian government to accept that and then make that public to get some guarantees in return. I don't think we can throw the Ukrainians under the bus publicly, but we can have the Ukrainians throw themselves under the bus with a lot of support, right? And I think that if you are the Ukrainian president, you recognize that saying that war is imminent gives the West more license to pressure you on that stuff. And he doesn't want that.

What would a deal look like? You said that perhaps encouraging Ukraine to accept and volunteer that they would never join NATO would be one piece of it. What else might it include?

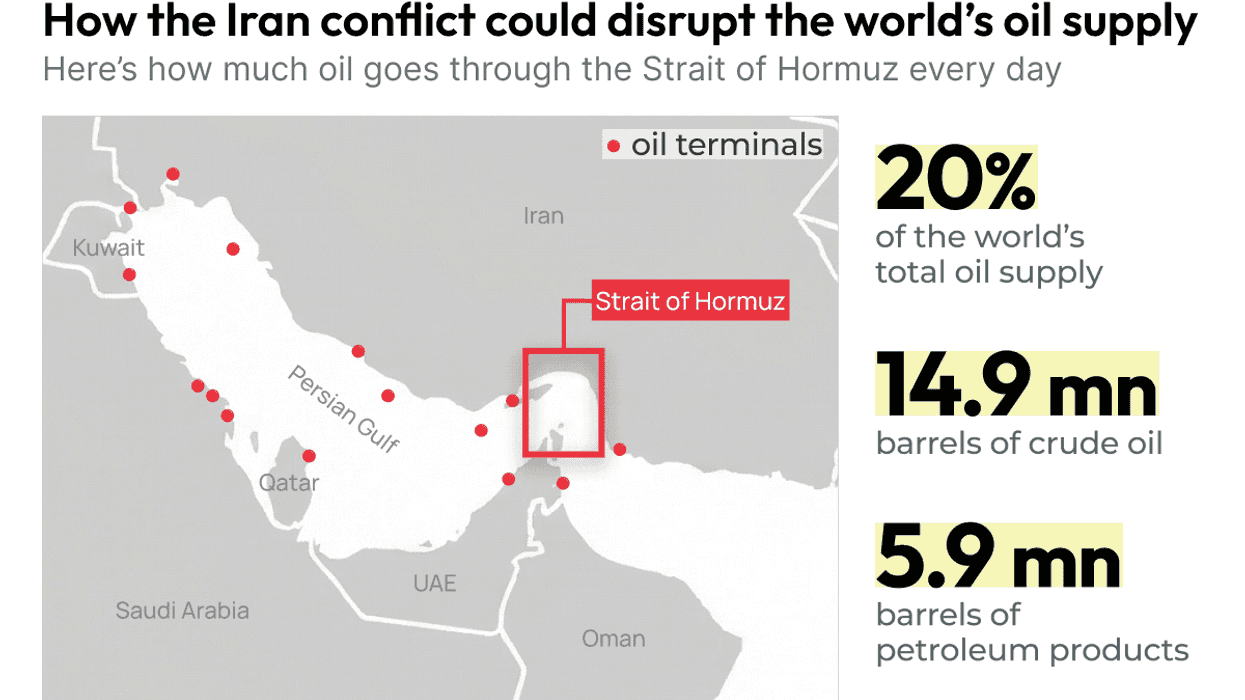

I think that you could have something that looks like an Iranian deal, where for five or ten years, the Ukrainians agree that they will not seek a membership action plan in NATO, and NATO assents to that. And NATO also agrees to the reestablishment of the NATO-Russia Council. There are limits on what kind of military exercises one can do with the Ukrainians. Maybe none at all. Only limited types of defensive weapons are allowed, there are inspectors, they can be capped. But in return, the Russians have to agree to limit where their forces can be near Ukraine and what they're doing, and they have to provide information in advance. And I think that kind of agreement could also have some reductions on intermediate range missiles, nuclear forces, and how close they can be to the borders of each. I mean, there are all sorts of things like that, that I think could be the basis of a meaningful negotiation between the Americans and the Russians. Ukraine would have to be a formal part of it, though clearly the deal would be struck primarily by NATO allies and Russia.

The US says that we're prepared to send 8,500 troops to join NATO forces if we're asked for them. We do not expect them to be on a frontline facing Russian forces anywhere, but where do you think they could be sent? And under what circumstances could they actually see fighting?

Under no circumstances would they see fighting in Ukraine. It's inconceivable to me that we would provide support and to defend Ukrainian military forces. This is not Taiwan where we've been intentionally ambiguous about that. We have sent only very clear signals to the Ukrainian government: “If the Russians invade you, you'll have some equipment, but we are not risking American men and women in that fight.” Now, there is a small exception, which is that if the Russians were to invade suddenly and Americans on the ground were thought to be at risk, I certainly believe that we would deploy troops as we did in Afghanistan at the airport to try to ensure that we could get them out quickly and safely. Other than that scenario, the Americans would be sending troops to the frontline NATO states. So it's the Baltic states, it's Romania, it's Bulgaria. There've already been some redeployments by other NATO allies into those countries. We've seen that recently from France, from Denmark, from Spain, I think one or two others. We're talking small numbers, we're talking some jet fighters. There's a new frigate in operation in the Black Sea.

But it’s about sending a message. I suspect that Putin is surprised with the level of cohesion of US-led NATO response to what the Russians have done so far. And I think he'd be surprised first because of what happened in Afghanistan, but also because of how divided the United States tends to be on most things. The United States is not divided on this at all. There is a very broad bipartisan agreement on what the Americans need to be doing here.

Well, there are some Republican holdouts who are saying that the US should not be getting involved there at all. Why fight in Ukraine, or why even care about Ukraine when we've got problems at home?

Yeah, there are like five of them and they're generally jokers. But in my life, at least as a political science professional for the last 30 years, I have never seen a crisis where there is so much agreement on policy, internally and bipartisan. Not China, not Iran, not Iraq, not Afghanistan, not Venezuela. I mean, literally you have agreement on: Ukraine should not be in NATO. You have agreement on: we should be sending the Ukrainians significant defensive military capabilities. You have strong agreement on: we should be engaged in diplomacy with the Russians. Strong agreement on: there should be massive consequences if the Russians engage in even a small military incursion and they should have a heavy economic component. And then finally, we have agreement on the need to get the Europeans as onboard as humanly possible. That's a hell of a lot of agreement between the Democrats and Republicans.

Biden has threatened some pretty novel sanctions against Russia apart from just the currency and freezing some assets, possibly barring Russian individuals and industry from key technology. How aligned is NATO on a sanctions package? What are the teeth there? And is this truly debilitating for the Russian economy?

NATO is aligned, I would say at least 80%, on the range of economic sanctions that have been discussed so far. The new German chancellor was squishy on the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, which has been built but is not yet operational. But there's been a lot of high-level diplomacy that's gone on behind the scenes between the US and the Germans, and the Germans have gotten there. That is a big deal. And that is why we have German Chancellor Scholz coming to Washington to meet with President Biden on February 7. The French were talking about going their own way for like an afternoon. Diplomatically the French are never easy to corral, but the fact is that they've been very transparent and engaged with the Americans around the Normandy format talks that they've had over the course of these past few days.

I think that the economic sanctions that we are talking about are serious, they're severe. But I also think that the Russians have baked that in. I don't think that the economic consequences by themselves are sufficient to prevent them from engaging in military escalations.

Is that because they wouldn't be crippling to the economy or because Putin's power is so complete that even if the economy is in pain, Putin has enough power to endure that?

When you see what's happening in Belarus and Kazakhstan, certainly Putin thinks that's the kind of thing that could happen in Russia. So in a sense that’s why he needs his economy to do well. But in the near term, the Russian economy is going quite well right now. Gas prices are very high, oil prices are very high, and the Russians are running surpluses right now. So they certainly feel that in the near term, their ability to have a resistance economy is significant. And they've also been living with a fair level of American sanctions and European sanctions for quite a while right now. I suspect that Putin also believes that if the gas gets cut off to Europe, that China will pick up that energy. I suspect that discussion has already been had. I have no intelligence on that, but I suspect that they have. It feels to me that both sides feel confident around that issue.

You've said this is a dangerous situation. Do you think what the Biden administration is doing is enough?

I don't know if it's enough. I would give the Biden administration pretty strong marks on this one. I was out there publicly castigating them pretty hard on Afghanistan. I think they made a lot of execution and operational mistakes. I think on this one, they've actually done a lot of things right, and they do have the allies on board and they do have the Russians taking the negotiations seriously. And the Ukrainians said that they were read into the letter that was sent to Moscow before it was sent, and they didn't have any problems with it. That's a meaningful thing that a lot of other administrations would've gotten wrong. Hard to imagine the Trump administration being able to handle this level of diplomacy, for example.

Now, I don't like them bringing this to the UN. I don't like it because the Chinese haven't said very much so far on this issue and I don't want them to. And I fear that if this becomes a big Security Council issue, the Chinese will veto along with the Russians and they will become a more public voice on this issue, which we do not want. That is against our interests. We want the Chinese on the sidelines. I don't like the idea of chest-thumping on human rights at the Security Council where we're not going to get the outcome we want.

I hear from people in my audience, saying that they’re frustrated that the administration is spending time and energy and money on Ukraine when we have so many crises here at home. Can you speak to Americans who don't feel that this is our fight? Why is it important for America to be involved and for regular Americans to care about what's happening with Russia and Ukraine?

Look, I'm very sympathetic to Americans wanting out of Afghanistan. We spent trillions of dollars and thousands of young men and women were killed and hundreds of thousands came back with post-traumatic stress disorder and horrible debilitating injuries. And for what? If I'm a young person, if I'm a poor person, I am angry about the way that so-called globalist elites have been more than happy to use my kids as cannon fodder.

We are not doing that here. Here, we are trying to defend an independent and legitimate government against hostility against their civilians by an authoritarian dictatorship. And we are not risking the lives of Americans, but we are utilizing our alliance, and we're doing it together. I accept that all the years of exporting democracy, we should have kept a little more at home, might we sent a little too much abroad as it were. And that we've got much bigger problems we need to deal with here in the United States. But we can keep our alliance together. And yeah, we're taking the leadership role because we're the most powerful country in the world.

I think that a lot of Americans don't know what we stand for anymore. A lot of Americans will look at the Statue of Liberty and recognize we don't take people in anymore. And it doesn't feel like the America I grew up with. My grandma went to Ellis Island. Doesn't feel great to me. But if you see what we're doing right now with our allies in NATO versus Russia on Ukraine, that's what America is. That's who we are as a country. And I don't want to lose that.

🔔 And if you haven't already, don't forget to subscribe to my free newsletter, GZERO Daily by Ian Bremmer, to get new posts delivered to your inbox.