The lights are going out in Cuba. Commercial flights into Havana can no longer refuel at the international airport. The capital's bus network has largely ground to a halt. Trash is piling up on the streets, with most collection trucks sitting idle for lack of diesel. Many embassies are closing or drawing down staff. More than half the island’s electric grid is offline. Cuba’s economy is in free fall – one engineered in Washington.

Fresh off his Venezuela win, President Donald Trump has turned his sights on the Cuban regime, betting he can replicate the playbook that worked against Nicolas Maduro: strangle the economy until the regime cracks and cuts a deal. It's a bet Trump has made before, during his first term, when he reversed the Obama-era loosening of relations with Cuba and implemented a “maximum pressure” campaign.

In fact, the United States has been trying to get rid of Cuba's communist government since Fidel Castro marched into Havana in 1959. The playbook has included nearly everything. A full-blown military invasion at the Bay of Pigs in 1961 that collapsed within two days. Hundreds of CIA assassination plots involving poisoned cigars, exploding seashells, and mafia hitmen. A sweeping trade embargo imposed in 1962 that's now the longest-running sanctions regime in US history. Covert sabotage campaigns under Operation Mongoose featuring bombings of sugar refineries and civilian targets. And decades of diplomatic isolation meant to strangle the regime economically and politically.

None of it worked. Cold War Soviet subsidies kept Cuba afloat for thirty years. The regime used US aggression to rally Cubans around the flag. Havana's security apparatus crushed dissent before it could organize. Even during the so-called “Special Period” after the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, the government survived catastrophic pressure. Oil imports dried up. The economy shrank 35%. Cubans survived on about 1,000 calories a day. GDP didn't recover to pre-crisis levels until 2000, but the Castros held on, tightening rationing, opening limited markets, and grinding through a decade of blackouts and food shortages.

The US Congress codified the embargo into law in 1996 with Helms-Burton, making it nearly impossible for any president to lift sanctions without congressional approval. But codifying a failed policy didn’t make it any more successful. A 1960 State Department memo laid out the original intent: bring about “hunger, desperation and overthrow of government.” Over six decades later, the government's still there.

Could this time be different?

Cuba is more isolated than it's been since 1991. With Maduro in US custody and Venezuela now firmly under Washington’s thumb, Havana has lost its main patron of the past two decades. Russia, which maintains a military and intelligence foothold on the island, is fully committed to its war in Ukraine and can't afford to prop up distant allies. China hasn't stepped in to fill the gap. The Venezuela operation also sent a message. US special forces killed at least 32 Cuban intelligence and military officials who were guarding Maduro, suffering no American casualties. The US has far more asymmetric leverage and military might than it did during the Cold War.

And the economic pressure from the Trump administration is sharper and more targeted than the old embargo ever was. Cuba produces only about 40% of its oil needs domestically, and Washington has blocked over 70% of imports after convincing both Venezuela and Mexico to stop shipments – and threatening tariffs on any remaining oil suppliers. The island has now gone over a month without a major fuel delivery. New US legal restrictions have dried up the flow of remittances – already down 80% since 2021 – from Cuban-Americans, one of Havana’s few remaining hard currency sources. And the Trump administration is systematically dismantling Cuba's overseas doctors network, cracking down on the regime’s single largest revenue stream to the tune of $6 to $8 billion annually, by sanctioning officials, restricting visas, and pressuring host governments. Guatemala, Guyana, Antigua and Barbuda, the Bahamas, and Grenada have already ended or scaled back their programs.

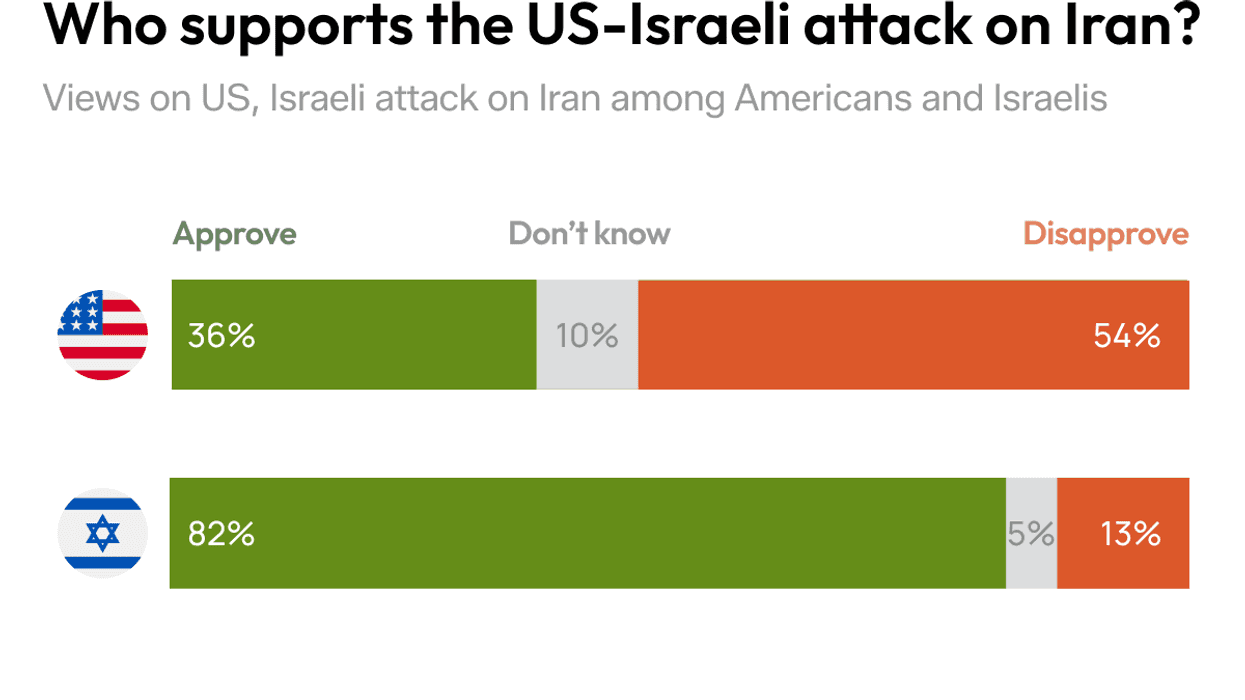

Unlike Venezuela or Iran, US military action isn't on the table in Cuba. The island lacks Venezuela's oil reserves and Iran's nuclear program – the kinds of strategic assets that elevate stakes and justify military risk. Instead, Trump’s strategy is economic strangulation plus diplomatic backchannels – the same approach that just worked in Venezuela (though likely without the special forces raid). The plan is to ramp up the pressure to accelerate Cuba’s collapse, wait for the regime to crack from within, and cut a deal with whoever is willing to agree to more US-friendly policies. As in Venezuela, where the Trump administration kept Maduro's Vice President Delcy Rodríguez in power as acting president, the White House is willing to leave some Castro family members and officials in place rather than attempt regime change. A more flexible and transactional government that opens the economy to tourism and real estate investment, cooperates on migration, and distances itself from Russia would count as a win. That's a much lower bar than a democratic transition, and it’s one Trump’s team thinks they can achieve.

The problem with this theory of victory is that Cuba's government is more ideologically committed and better entrenched than Venezuela's ever was. Unlike Caracas, where corruption and factionalism created exploitable rifts, Havana's leadership has been singularly focused on survival for 67 years. The regime has weathered humanitarian catastrophe before, and it crushed the largest demonstrations in decades in July 2021. Its security apparatus makes finding internal collaborators harder than in Venezuela. Gaesa, the military-run conglomerate that controls roughly half the economy, ensures the armed forces have a direct stake in the system's survival.

There's no organized opposition, no Edmundo González or María Corina Machado waiting in the wings. And unlike Maduro's kleptocratic inner circle, much of Cuba's leadership are true believers, harder to buy off and flip. Venezuela had Delcy Rodríguez, a regime insider willing to cooperate with Washington to save herself and preserve some continuity. Cuba has no equivalent. Even if officials privately question the government's direction, fewer are willing to risk becoming the next dissident locked away for 20 years.

Still, Havana is more vulnerable now than at any point since the Special Period. The economic pressure is working, in the sense that the humanitarian crisis is deepening. Satellite imagery shows nighttime light levels in major eastern cities have dropped as much as 50% compared to historical averages. President Miguel Diaz-Canel acknowledged last week the country faces a “complex energy situation” and announced fuel rationing, a four-day workweek for state employees, and the postponement of cultural events. He said Cuba is open to talks with the US “without preconditions” as long as regime change isn't on the table.

The White House is convinced that total economic collapse is a matter of time. “Cuba is right now a failed nation,” Trump said Monday. “We're talking to Cuba right now ... and they should absolutely make a deal.” Secretary of State Marco Rubio is leading the backchannel negotiations – reportedly including secret and “surprisingly friendly” talks with Raul Castro’s grandson, Raulito – and has publicly framed Washington’s terms: if Havana wants sanctions relief, it must liberalize its economy. He stopped short of detailing formal conditions, but the demand marks the clearest articulation yet of the administration’s off-ramp. “It doesn't have to be a humanitarian crisis,” Trump told reporters recently. “We'll be kind.”

For Trump, this is a bet with limited downside and meaningful upside. If the pressure campaign fails, he moves on without losing much: no American casualties, no multi-trillion-dollar occupation ala Iraq or Afghanistan. The political cost at home is minimal – Cuba barely registers for voters outside South Florida.

But if it works, even partially? It would accomplish what none of Trump’s predecessors going back to John F. Kennedy could, while dealing another blow to Russia and embarrassing Latin America’s left to boot.

The Cuban regime has survived 67 years of US pressure, and it will probably survive this too. But “probably” is doing a lot of work here – and for an administration that is only asking for a more pliant and US-friendly Havana, it may be enough. After seven decades of failure, Washington may have finally found a version of this bet worth taking.