Al-Qaida is resurging in Afghanistan. The militant group is recruiting, raising funds, positioning itself to conduct long-distance attacks, even upping its propaganda, and remains close to the Taliban.

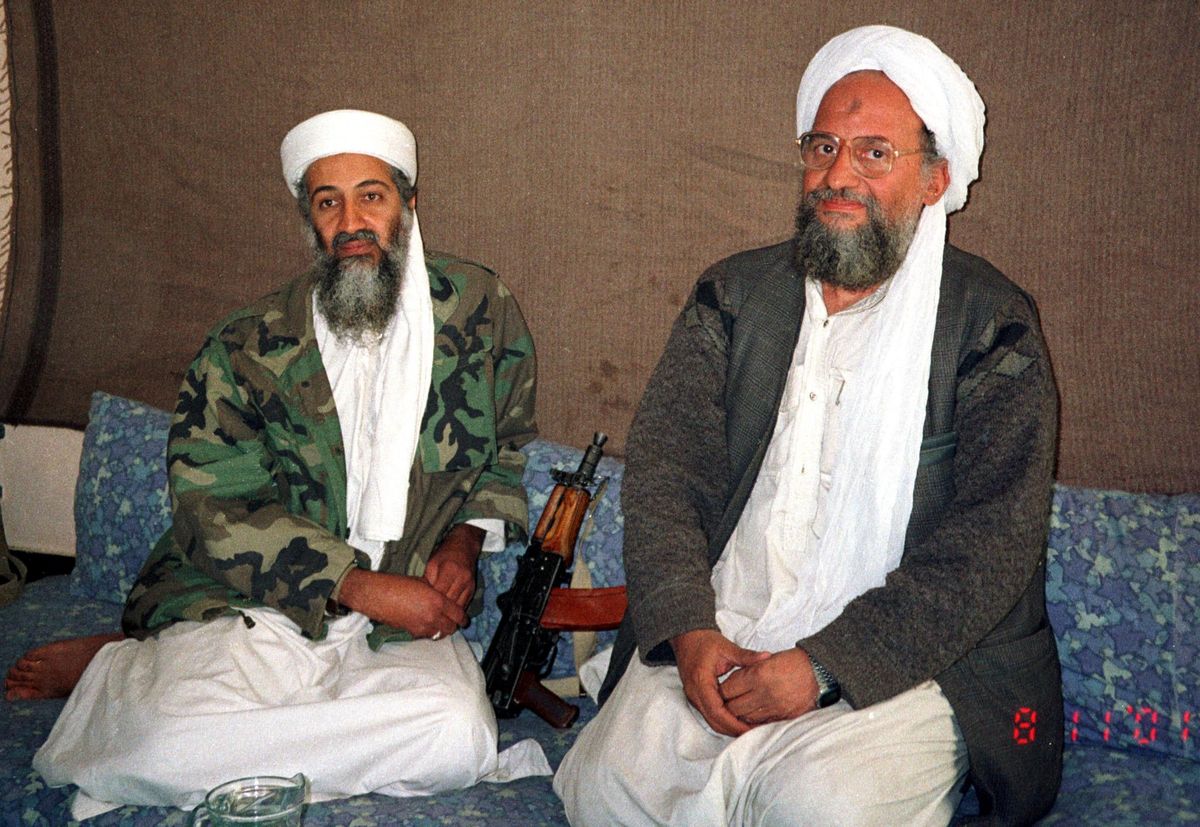

That’s according to a new UN Security Council report, compiled with intelligence from member states. The report, released by the UN office monitoring international sanctions on the Taliban, has further claimed that al-Qaida’s core – under Dr. Ayman al-Zawahri’s leadership and estimated to be several dozen-people strong – is located in eastern Afghanistan’s Zabul and Kunar provinces, along the border with Pakistan, where the terrorists have enjoyed a “historical presence.” It also noted that some members were reportedly living in Kabul’s former diplomatic quarters, where they have access to the Taliban-run Ministry for Foreign Affairs, though this wasn’t confirmed by the investigators.

A familiar face reemerges

Al-Zawahri’s communications suggest he may be able to lead the group more effectively than before the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan. The Egyptian-born physician and deputy to Osama bin Laden has appeared in eight videos since the Taliban took over in August 2021. His most recent production – praising an Indian Muslim woman for her defiance of a hijab ban – was in April and provided the first real proof of life for the 72-year-old in recent years.

The findings come at a crucial time as the Taliban are rolling back freedoms enjoyed by Afghans for the last two decades while grappling with international isolation and a massive humanitarian crisis. Women and girls have been particularly targeted by the Islamist regime, which also faces an insurgency of its own with the growing threat from ISIS-Khorasan (ISIS-K) – the local affiliate of ISIS, an offshoot of al-Qaida but now a fierce competitor of both al-Qaida and the Taliban.

However, the Taliban’s lack of will or capacity to restrain terror groups – whether they’re targeting Afghanistan or its neighbors – is generating regional ripples. Pakistani diplomats say that since the beginning of 2022, more than 100 of their military and border security personnel have been killed in attacks from groups based in Afghanistan. In April, in an attempt to push back against Taliban inaction, the Pakistanis started taking unprecedented, direct action, conducting air strikes within Afghan territory to target the so-called Pakistani Taliban, the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan, terrorists allowed freedom of movement and action by the new regime in Kabul.

In Washington, moves have been underway for months to tackle the emerging threat of both al-Qaida and ISIS-K. On Wednesday, Pakistani and US security officials – in regular contact since the Taliban takeover – met to discuss cooperation on counterterrorism efforts, including joint operations and intelligence-sharing, rebuilding Washington’s visibility (lost with the pullout), and also finding “creative” ways to handle the Taliban regime, a Pakistani official said. The Taliban are yet to be recognized by a single foreign government, but as the de facto authority in Afghanistan, they must be dealt with for any counterterrorist objectives, insisted the official.

It’s not too bad … yet

While the UN assesses that al-Qaida enjoys greater freedom under the Taliban, it also says the group’s operational capacity is limited – for now – and that the Taliban are holding the terror group back.

“It is unlikely [for al-Qaida] to mount or direct attacks outside Afghanistan for the next year or two, owing to both a lack of capability and Taliban restraint,” the report said while warning that al-Qaida will regenerate that capability and that the Taliban’s commitment to restraining the group is uncertain in the medium- to long-term.

Some regional experts remain skeptical that al-Qaida can pose a real threat. Abdul Basit, a research fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore, said that al-Qaida’s potency is an exaggeration.

“al-Qaida has been reduced to a former shadow of itself. It lacks a charismatic leader to revive [it] anytime soon,” said Basit, claiming that al-Zawahri doesn’t have bin Laden’s leadership skills. Also, he pointed to something the report corroborated: al-Qaida under the Egyptian physician has not inspired the type of massive international inflow of jihadists expected with the Taliban takeover.

“It does not suit the Taliban to give al-Qaida a free hand in Afghanistan,” he said, noting that Taliban support for the terrorist group would likely pave the road to a US return to the region – not with ground troops, but with an “over the horizon” counterterrorism footprint.

Pakistani security officials, with the advantage of proximity, say they have evidence the Taliban have “accommodated” al-Qaida and instructed them to “lay low.” Terrorism analysts like Asfandyar Mir, a senior expert at the United States Institute of Peace in Washington, agree with Islamabad’s assessment but question how long the Taliban will be able to exercise such control.

“al-Qaida is there in Afghanistan, has the Taliban’s help to remain in the country, and continues to steadily build up. Yet it is also under strong instructions from the Taliban to not plot attacks from Afghanistan,” he said.

“But a break in the Taliban’s relationship with the international community or their internal political jostling can make things more favorable for al-Qaida,” Mir added.

Though they have fought together on the battlefield against the US and its allies, there is a fundamental difference between the Taliban and al-Qaida. The former sees itself as an Afghan resistance movement, dominated by the values of ethnic Pashtuns. It doesn’t have transnational aspirations and professes to only implement its harsh version of Islam within Afghanistan. The latter, meanwhile, has a larger, more ambitious transnational agenda. It is expansionist and export-oriented by its very nature, with the goal of establishing a global caliphate.

With ISIS-K, a competitor with similar ambitions, on the rise – estimated by the UN to have swelled to 4,000 members – the question then becomes: how long can the Taliban continue to restrict al-Qaida from its plotting within Afghanistan, or when might al-Qaida defy the Taliban to pursue its operations independently?

While the UN says that al-Qaida and ISIS-K are not capable of mounting an international offensive before 2023, Afghanistan’s internal political dynamics will also weigh into the more experienced terrorist group’s calculus, ability, and intent to attack. Al-Qaida, after all, has a history of striking internationally when the Taliban are strong nationally.

“al-Qaida may also decide eventually that enough time has passed and the Taliban’s government is stable enough to survive a deniable terror attack,” said Mir.

This comes to you from the Signal newsletter team of GZERO Media. Subscribe for your free daily Signal today.