As I look ahead to 2024, there is one phrase that keeps coming back to me: The wheels are coming off.

For years I’ve been warning that our G-Zero world – characterized by a lack of global leadership and the geopolitical conflict that grows as a consequence – was gathering speed. That acceleration is only increasing today, while channels of international cooperation – multinational institutions, traditional alliances, and global supply chains – are losing their ability to absorb shock.

Today, when we mention war, we have to specify which one we’re talking about. The war that ended the peace dividend, remaking the security architecture of Europe? Or the war destabilizing the Middle East, threatening global religious conflict? Serious doubts have emerged about the economic well-being of China, the nation that along with the United States has done most in recent decades to power the global economy. Serious doubts have also emerged about the political well-being of the United States.

These urgent challenges make for an unprecedentedly – in my lifetime at least – dangerous state of global politics.

Israel-Hamas war

The now two-month war that has followed the terrorist attacks of Oct. 7 is expanding without guardrails.

Hamas is responsible for the murder of 1,200 Israeli citizens, more than 90% of them civilians, and it continues to assert the right to kill more Israelis in the future. In response, Israel’s government feels rightfully entitled to eradicate Hamas, but it is doing so with little regard for the more than two million Palestinian civilians who can’t escape the line of fire.

The United States has at least some leverage over its ally Israel (though given political challenges at home, it’s less than many would think), and it is trying to influence the conduct of the war and the scale of its carnage. Working with Qatar and the United Nations, the Biden administration has helped bring humanitarian aid to Palestinians trapped in Gaza as well as secure the release of some Israeli hostages and Palestinians in Israeli custody. The US government has also pressed Israel to minimize civilian deaths as it works to destroy Hamas. Yet for much of the world, these moves are too little too late. As a result, the US today finds itself nearly alone in supporting continued war. Indeed, the US is as isolated on this issue globally as Russia was when Vladimir Putin invaded Ukraine nearly two years ago (!).

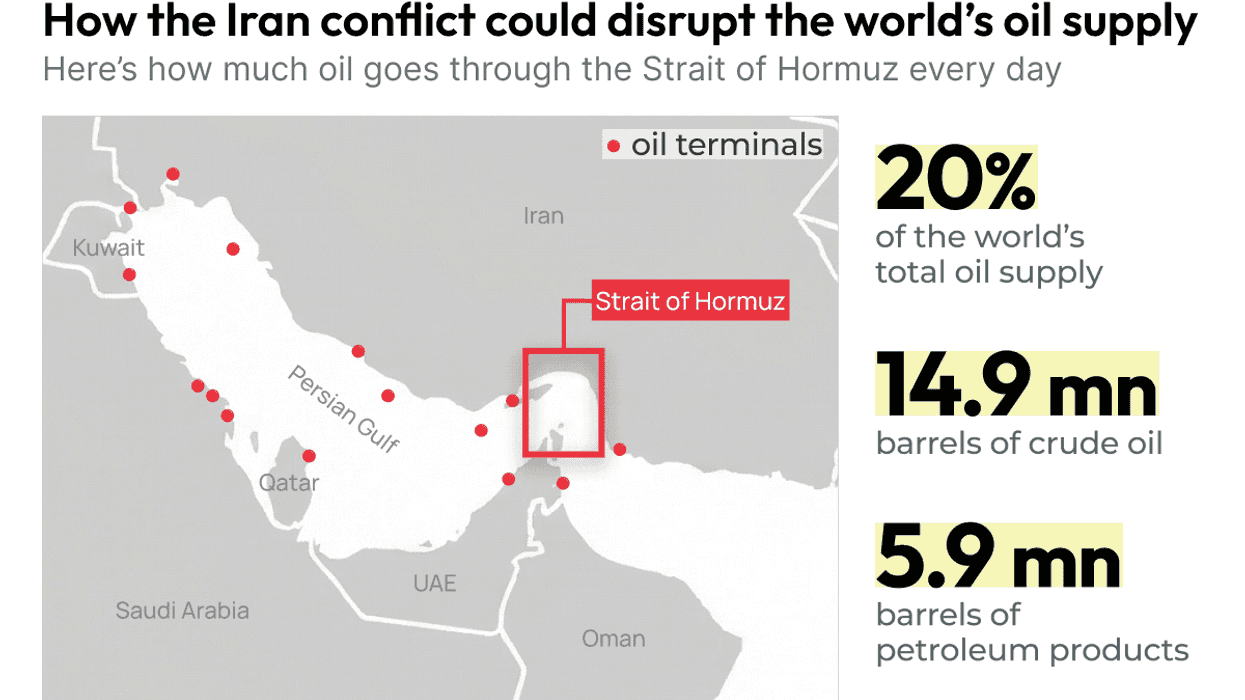

President Joe Biden has so far had more success in avoiding an expansion of the war beyond the borders of Israel and Gaza. But that work will become more difficult as the next phase of the war in Gaza advances. As we’ve seen over the past week, the Iran-backed Houthis in Yemen are already stepping up their attacks on American military vessels and commercial transit. More escalation from them, Hezbollah, and other Shia militant groups in Iraq and Syria is sure to come.

Under no circumstances will Biden renounce the US alliance with Israel – but Israel has permanently lost some of its traditional support inside the United States. US public opinion has shifted with the nation’s demographics. Younger voters increasingly side with the Palestinian position, and more and more Americans are publicly questioning Israel’s continuing occupation of the West Bank and even its commitment to democracy. These concerns will only grow as Palestinian civilian casualties rise.

We are no closer to a resolution of this war today than we were six weeks ago. Indeed, the war is set to escalate further, and there are no snapback mechanisms in place to stop that from happening.

Russia-Ukraine war

Then there’s the war no one asks me about anymore – the one still raging in Ukraine. Around this time last year, I noted that Russia controlled about 20% of Ukraine’s territory and Ukrainian forces were unlikely to ever fully evict Russian fighters. Twelve months later, almost nothing has changed – and that which has has changed for the worse.

In the past year, Putin followed through on threats to exit a UN-brokered deal to allow Ukrainian grain exports through the Black Sea. Higher oil prices have helped boost Russia’s domestic production of missiles and ammunition to greater volumes than before the war. North Korea is sending Moscow more of both, and Iran continues to provide drones. Failed mutiny aside, Putin’s strategic position has improved over the past year – and certainly over the last two months.

Questions have emerged about the staying power of Kyiv’s main backers in America and Europe. In the US, Republicans increasingly don’t want to spend money on Ukraine. That will be even more true once Donald Trump gets his party’s nomination and makes ending support for Ukraine an electoral battle cry. In Europe, support for Ukraine remains high, but countries now have much less capacity to absorb refugees or to help fund Ukraine’s war effort. Europe’s economic support and America’s military support for Ukraine are becoming less certain simultaneously.

Meanwhile, Ukraine’s counteroffensive has moved the front line less than 25 kilometers since the summer – and with its installation of defensive fortifications in the past few days, it’s safe to say the operation is now over. In recent weeks, Russia has expanded missile strikes across Ukraine to the highest levels we’ve seen this year. If Putin orders an additional troop mobilization in the fall, President Volodymyr Zelensky will struggle to match it, making it entirely possible Russia could take even more territory from Ukraine. Zelensky, not Putin, now faces increased pressure to move toward a negotiated settlement.

We know what the outcome will be: partition. Ukraine simply can’t get its land back. Of course, nobody is going to formally announce that (well, other than me). It’s unacceptable to the United States, Europe, and most of all the Ukrainians. But we live with lots of things that are unacceptable – a nuclear-armed North Korea, Assad in power in Syria, the end of democracy in Venezuela. This is just one more such thing.

Ukraine is at risk of losing, but Russia has no way to “win.” Whatever longer-term gains its forces can make on the ground in Ukraine, NATO is now strengthened by new members Finland and Sweden. This month, the EU will open a membership process for Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova, an outcome that wasn’t on the table before Putin ordered his invasion. Russia has faced 11 rounds of sanctions, with more on the way. Half of its sovereign assets have been frozen. Europe will no longer buy Russia’s commodity exports, which instead must be sold to China, India, and others on the cheap. Moscow has been rendered permanently dependent on Beijing. All of this, just to get pieces of eastern and southern Ukraine that will take years and years to consolidate …

Which leaves us with a bigger problem: Russia is on the road to permanent “rogue state” status. It’s the first time that’s ever been true of a G20 economy, never mind one with 6,000 nuclear weapons. We won’t be talking as much about Ukraine in another year, but I fear we’re going to be talking a lot more about Russia.

China’s economic challenges

The China “growth engine” no longer works the way it used to.

Youth unemployment stands at record highs. Manufacturing activity is contracting. The property sector is in serious trouble. Exports have declined on the back of inflation and historically high interest rates in the US and Europe. Foreign investment into China has turned negative for the first time since we’ve measured it. Property prices are declining, household wealth is contracting, and borrowers are no longer willing to underwrite property construction. Developers and lenders are defaulting. Revenues for local governments are drying up just as their debt servicing costs are rising. Domestic demand is stagnant, consumer sentiment is down, and growth is slowing.

China’s government response has been limited and incremental. Large-scale bailouts for distressed developers, shadow banks, and local governments are off the table for now. Headline growth may well come in at 5% this year, but the economy faces deflation caused by persistently weak consumer spending, slowing private investment, overcapacity, and mounting financial stress. The IMF now expects the Chinese economy to grow under 4% a year for the coming years; absent reform, this number could go lower, especially in light of unfavorable demographics, chronically high debt, and intensifying geopolitical competition with the US and its allies.

For the first time since the 1980s, the Chinese people fear that the next generation will not be better off than the present one. And the increasingly centralized, opaque, and capricious nature of Chinese policymaking – not to mention a series of disruptive policies such as tech crackdowns, the zero-COVID lockdowns and abrupt exit from them, and raids on foreign firms – has undermined the public’s confidence in Beijing’s ability to fix the problem.

The good news is that China remains a highly competitive economy, with an educated workforce, increasingly world-class infrastructure, and advantages in manufacturing, renewable energy, and electric vehicles as well as leading-edge innovation in frontier industries like advanced computing, AI, and biotechnology. China is also very politically stable, allowing President Xi Jinping to avoid the temptation to revert to unsustainable debt-fueled growth if he chooses. Only a systemic financial contagion or mass protests, neither of which looks likely in 2024, could force his hand. Instead, he will simply add stimulus at the margins and call on his people to persevere as they attempt to shift toward new drivers of growth.

The bad news is this means that Chinese growth is going to remain slower for longer, dragging down global growth with it. And the wrong policy choices could still leave China’s economy in a scenario of prolonged deflation, stagnant growth, and high indebtedness – much like what Japan experienced in the 1990s, but at a much lower level of development. That would be a massive problem for the world given China’s outsize role in the global economy.

America’s political dysfunction

Despite having a booming economy, the world’s most powerful nation has become the most politically divided and dysfunctional democracy of all the G7 countries (though the United Kingdom is competitive).

How dysfunctional is it? Earlier this year, personal rivalries among Republican lawmakers left the US House of Representatives without a leader – and, therefore, unable to pass legislation – for the longest period in 160 years. The last time divisions within the House stopped business in this way, the main issue dividing them was the legal status of slavery.

Now we face the 2024 presidential election, where we’re on track for the most unwanted sequel since “National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation 2: Cousin Eddie's Island Adventure.” Polls paint a bleak picture for the incumbent: Just 37% of Americans approve of Biden’s performance as president. More than 70% of likely voters say the 81-year-old Biden is too old for the job, and about 65% of voters don’t want him to be president again.

On the other side, there is the twice-impeached, twice-acquitted Trump. After he was defeated for reelection in 2020, the former president refused to concede, created a plan to remain in power, and incited a violent insurrection to stop the certification of Biden’s victory. He has been indicted on 91 charges in four separate criminal cases, and unless he’s elected next year, he faces prison time. Just 38% of Americans approve of his four years as president, and 60% don’t want him back in the White House. Yet he now leads all other Republican 2024 presidential candidates by more than 30 points.

Can Trump be president again? Absolutely. If the election were held today, Trump would win. The outcome a year from now looks more like a coin toss. But Biden does have one important advantage: There has never in American history been an election in which the challenger’s reputation matters at least as much as the incumbent’s. And that will make this race unusually – perhaps uniquely – difficult to forecast.

In the meantime, other governments – allies and rivals of the United States – are already calculating the opportunities, costs, and risks that US elections might create for them. In Beijing and Moscow, in Tel Aviv and Tehran, and in Kyiv, Pyongyang, Tokyo, and Brussels, policymakers must reckon with an unprecedentedly uncertain US election outcome that will dramatically impact the global role of the world’s most powerful country.

*******

These crises are worrying enough to cause even the calmest among us to lose sleep. But do not despair: Despite all the bad news, there is still good news out there. We just need to look for it since it doesn’t usually make the headlines. New international players and even newer technologies are creating opportunities that deserve our attention, too. I’ll cover these in next week’s column.