Graphic Truth

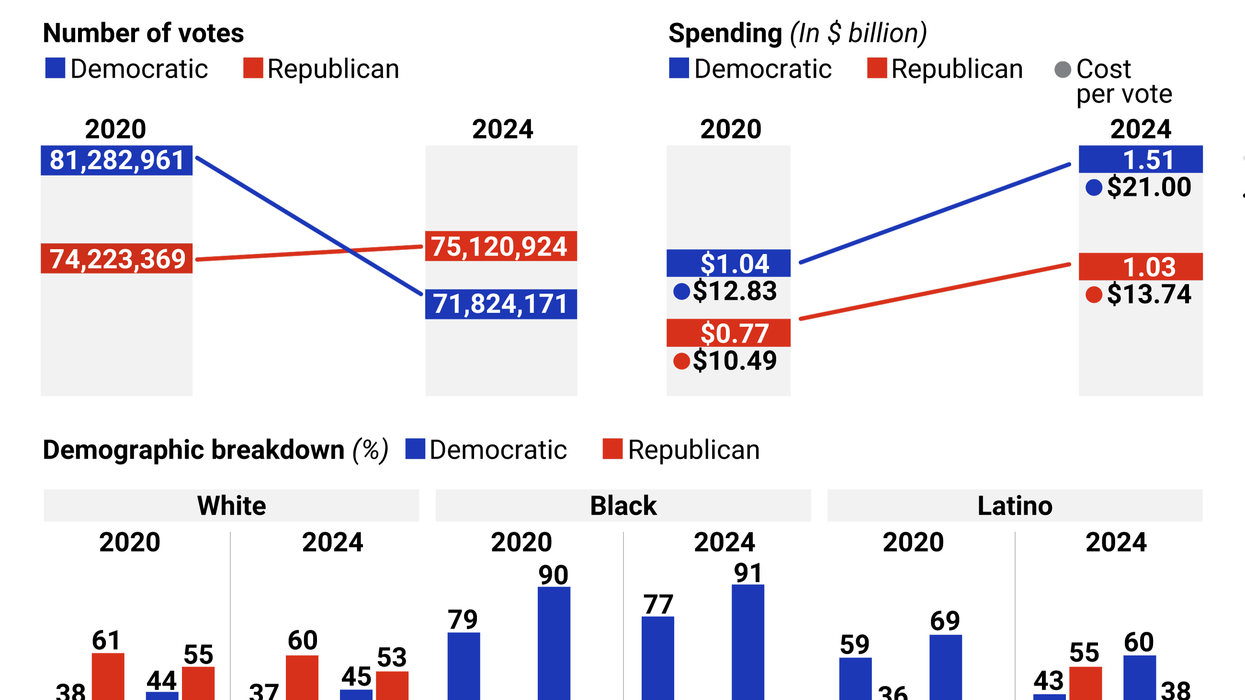

Graphic Truth: US voting shifts from 2020 to 2024

The votes are still being tallied following Donald Trump’s win in the US presidential election, but looking at preliminary voter data gives clues to what happened in the American electorate last week.

Nov 12, 2024