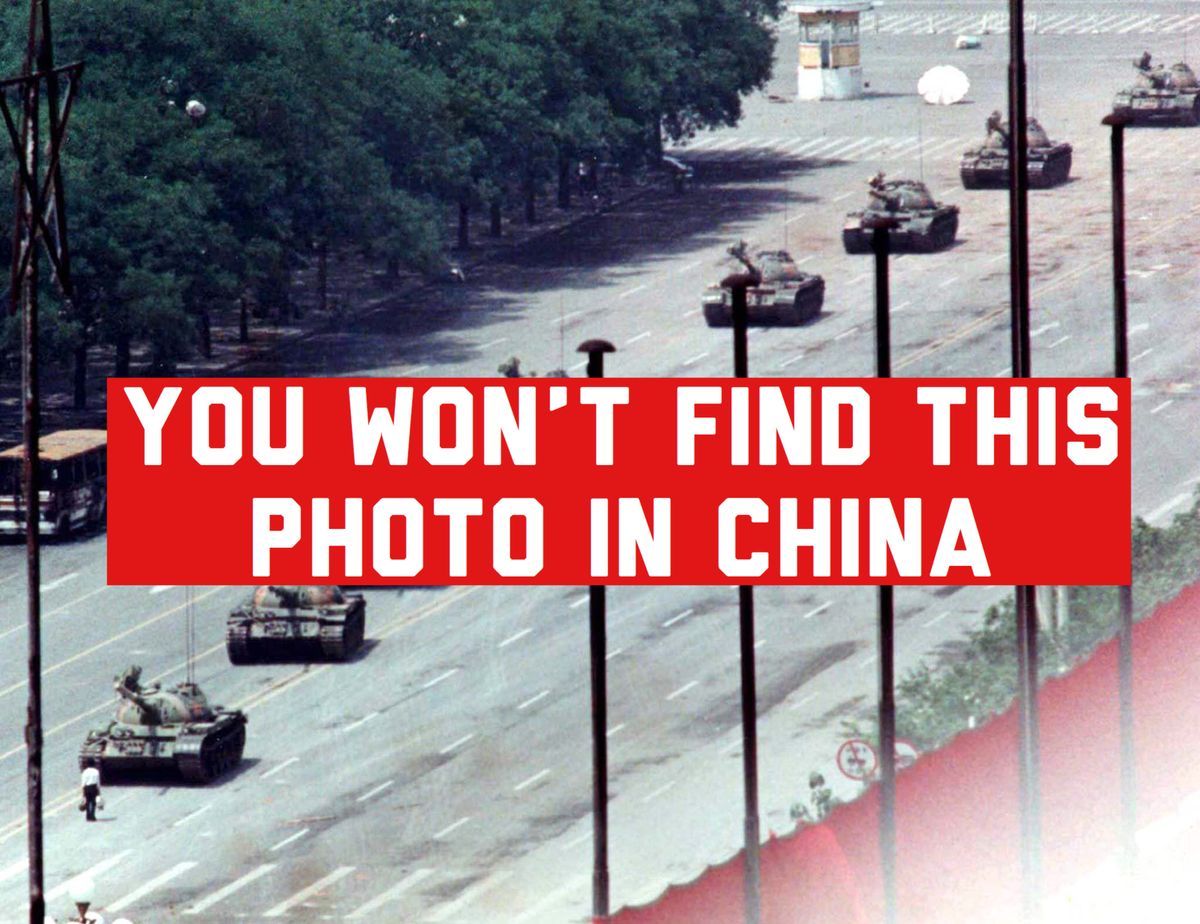

In the spring of 1989, Chinese students began gathering in Beijing's Tiananmen Square, at first to mourn the death of reformist leader Hu Yaobang and then in hopes of persuading their government to allow greater political freedom across the country.

Over a period of six weeks, the crowd swelled as older people joined and the list of demands broadened. The occupation of the square took on a life on its own, and some within the Communist Party leadership began to see a threat to their monopoly on political power.

The contest for control of the square soon became a battle for information. Protest leaders assigned lookouts to watch for any approach of troops. Any sign of movement by police or soldiers sent protesters scrambling to landline telephones in nearby buildings to call supporters to flood the square to make it more difficult for security forces to enter.

On June 4, 1989, under cover of darkness, Chinese tanks finally pushed into Tiananmen, crushing the protests and killing hundreds, perhaps thousands, of people.

On Tuesday of next week, many around the world will mark the 30-year anniversary of that event, a moment that changed China and the trajectory of world history. But, of course, the occasion will not be marked inside China, at least not publicly. That's because gaining access to the history of Tiananmen is, for most Chinese, still a battle for information, even if it's no longer a fight over landline phones or state-run TV and radio.

Hundreds of thousands of people fill Peking's central Tiananmen Square

Reuters /Landov

Hundreds of thousands of people fill Peking's central Tiananmen Square

Reuters /Landov

Only those over the age of 35 have any personal memory of the event. And while today China's citizens can use digital and social media to speak directly with one another, the government still controls communications and access to information. Social media accounts in China must be registered to users' real names, and tech companies are required to give the government access to all of their users' information if asked to do so.

Beyond keeping Tiananmen references off the traditional airwaves, advances in artificial intelligence also allow government computers to patrol the Internet in search of any reference to the Tiananmen protests and crackdown. The numbers 46 and 64, potential references to June 4, are removed from online posts. In 2012, censors briefly blocked access to the search term "Shanghai Stock market" after the index coincidentally fell exactly 64.89 points on the anniversary of the massacre.

Terms even loosely associated with the protests and crackdown are diverted to unrelated results. Video recognition software is programmed to scrub away any photographic reference to the events.

Three decades later, it's clear that China's leaders still fear the Chinese people and what they might want more than they fear any threat from abroad.