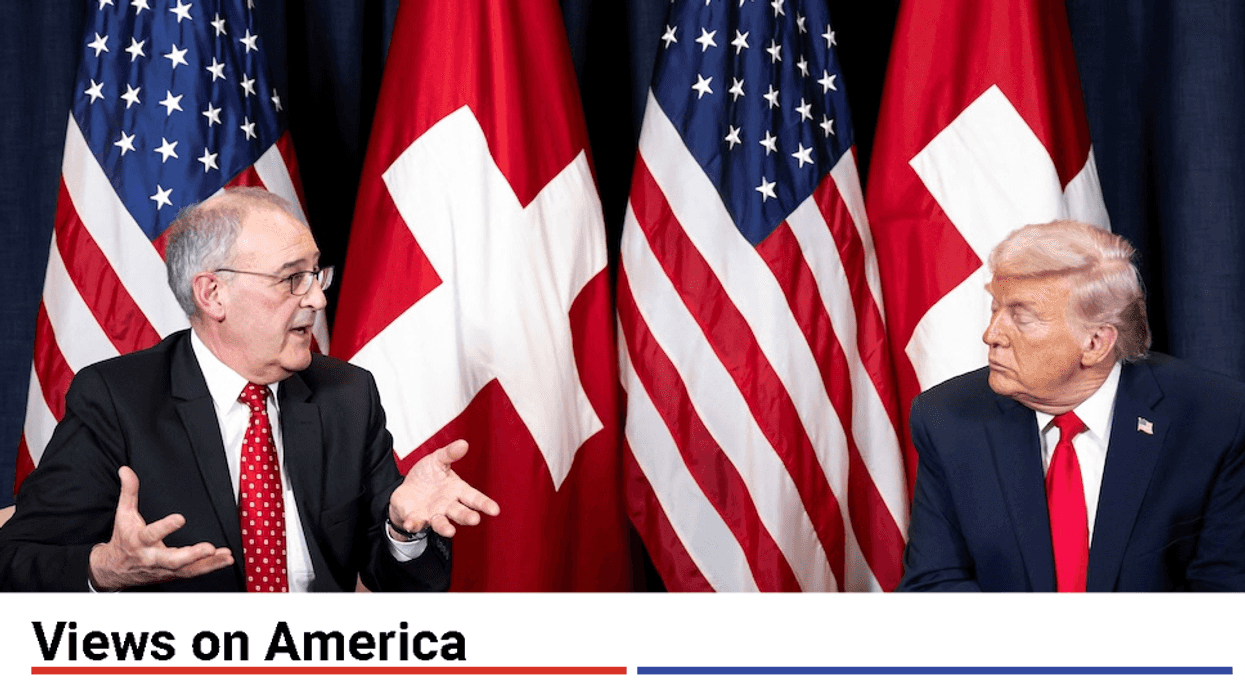

When Canada’s Prime Minister Mark Carney took to the stage last week at Davos, the typically-guarded leader delivered a scathing rebuke of American hegemony, calling on the world’s “middle powers” to “act together” as a buffer against hard power. Though Carney didn’t mention him by name, the speech was aimed squarely at US President Donald Trump.

“Let me be direct: We are in the midst of a rupture, not a transition,” Carney said. “Great powers have begun using economic integration as weapons. Tariffs as leverage. Financial infrastructure as coercion. Supply chains as vulnerabilities to be exploited.”

The world took notice of Carney’s speech – including Washington. It also came just days after Ottawa struck a deal with Beijing to lower tariffs on some Chinese electric vehicle exports in return for lower duties on Canadian canola oil. The Saturday after the speech, Trump threatened a 100% tariff on Canada if Carney completed the deal with China.

South of the US border, meanwhile, Mexico’s leader is taking a very different approach to dealing with Trump.

President Claudia Sheinbaum has tried to play nice with her American counterpart. In December, she sided with him in the US-China competition for global power, slapping 50% tariffs on 1,400 Chinese imports. Last week, her government extradited 37 alleged cartel members to the United States, following pressure from the Trump administration to halt the drug trade. And yesterday, Sheinbaum announced she was halting oil shipments to Cuba – Mexico is now the island’s largest supplier – although she denied it was due to US pressure.

“She doesn’t engage in a direct confrontation with Trump,” Brenda Estefan, a politics professor at the IPADE Business School, told GZERO. “She plays more with a cool head.”

While Mexico and Canada face very different challenges when it comes to their relationship with Washington, their divergent approaches to the US president encapsulate how various liberal leaders have dealt with Trump. Sheinbaum – like NATO Secretary-General Mark Rutte and UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer – has tried to placate him (albeit in a less overt fashion). Meanwhile, Carney has adopted a similar tactic to Latin American leaders like Brazil’s Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and Colombia’s Gustavo Petro, using Trump as a political foil.

The contrast also comes as the US, Mexico, and Canada are set to review the terms of the USMCA trade agreement this July and host the soccer World Cup together. Eurasia Group, GZERO’s parent company, has warned the USMCA is at risk of becoming a “zombie” agreement – where it's neither extended nor killed, leaving North American trade in chronic uncertainty (see Risk #9 in Eurasia Group’s Top Risks report for 2026).

For Sheinbaum, a conundrum. There are two big reasons for Sheinbaum’s careful approach to Trump. First, she doesn’t want him to strike cartel targets in Mexico, something his administration has repeatedly threatened since the capture of Nicolás Maduro. Of all the countries in Latin America, the US is most likely to take action in Mexico next, according to Center for Strategic & International Studies senior adviser Juan O. Cruz, who was part of the National Security Council in Trump’s first term. Second, Mexico’s president wants a smooth USMCA review, since her country is heavily reliant on the US for both trade and foreign direct investment.

“Some 80% of Mexican exports go to the US,” said Estefan, most of which enter tariff-free because they meet the trade agreement’s requirements.

Pushing her in the other direction are her left-wing nationalist Morena party and her predecessor, Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO). The party despises the notion of US intervention, and the alleged links that Mexican lawmakers, both within and outside of Morena, have to drug cartels mean a strike could spark an internal backlash. At the same time, the shadow of AMLO, who founded Morena and handpicked Sheinbaum as his successor, still looms large.

“AMLO has been speaking of the importance of national sovereignty and the importance of Mexico dealing with its own problems,” said Eurasia Group’s Mexico analyst Andrea Villegas. “It makes it very difficult for Sheinbaum to accept [US intervention].”

This conundrum has started to hurt Sheinbaum politically. A recent poll found that 50% of Mexicans believe her government has handled relations with Trump badly or very badly, while only 29% think they have handled them well or very well. The president’s approval ratings, though still high, are significantly lower than they were a year ago.

For Carney, a win-win. Ever since the start of his premiership last year, the Canadian PM has been rewarded for tussling with Trump. In fact, Carney has the US leader to thank for helping him win last April’s election: polls had him trailing the opposition Conservatives by some distance, until Trump’s tariff war sent Carney’s stock rising. His combative tone toward Trump made him seem like a tougher foil to the US leader, which helped propel him to victory. But he also gets rewarded when the two appear to be getting along, like during Carney’s White House visit last May.

“When things are great with Trump, people say Carney is able to have the ear of the president,” Catherine Loubier, who served as senior adviser to former Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper, told GZERO. “When things go sideways, then Canadians say, ‘He’s facing Trump, and he’s able to have leadership in the face of adversity.’”

Relations now look sour, but Loubier believes the two sides are simply pushing for trade concessions from one another ahead of the USMCA review in July. She said Ottawa’s trade deal with Beijing was more about “symbolism,” as the US and Canada remain heavily intertwined both economically and culturally. If anything, Carney could seek to exploit the current tensions by calling an election in the hopes of securing an outright majority.

“I think he would get his majority. There’s no doubt about it,” said Loubier.

Could Sheinbaum learn something from Carney? Sheinbaum’s position is far more precarious than Carney’s. For one thing, her country is not part of NATO, so the US could take unilateral military action against alleged drug traffickers in Mexico without subverting a transatlantic partnership formed in the aftermath of World War II. What’s more, Mexico is somewhat more reliant on the US than Canada, as it derives a greater share of its GDP from exports to its northern neighbor.

As such, Estefan believes it would be worthwhile for Mexico to diversify, much as Canada is trying to do. Instead, it seems to be going the other way, slapping tariffs on several countries – including China – while trying to placate a US president who keeps raising his demands.

“I see a Mexico-US strategy,” said Estefan. “What I don’t see is a Mexico-world strategy.”

For a video explainer of the alternate ways Mexico and Canada are dealing with Trump, watch this report from GZERO’s Zac Weisz.