Who exactly are the people representing America to the world? Chances are they’re “pale, male, and Yale”, as the saying goes. Even in 2024, the US Foreign Service – especially in senior positions – doesn’t look like the rest of America. African Americans, people of color, and women continue to encounter barriers to influential roles.

However, some Black diplomats — like UN Ambassador Linda Thomas Greenfield — have broken this racial ceiling and helped reimagine what an American envoy can be. Her predecessors, through the sweep of US history, encountered discrimination and racism both domestically and abroad and left an indelible mark on US foreign policy. To mark the end of Black History Month, GZERO highlights the stories of a select few:

Ebenezer Don Carlos Basset

Ebenezer Don Carlos Basset

Fair Use/National Museum of American Diplomacy

Born into a free Black family in Connecticut in 1833, Bassett broke racial barriers from the very onset of his career. He was the first Black student admitted to the Connecticut Normal School and taught at the pioneering Institute for Colored Youth in Philadelphia in the years before the Civil War.

His impassioned polemics for abolition and equal rights during the war thrust him into the political spotlight. President Ulysses S. Grant appointed him minister to Haiti and the Dominican Republic in 1869, Basset became the first African American to serve as a diplomat anywhere in the world. Upon his return to the United States, he served as American Consul General for Haiti in New York City.

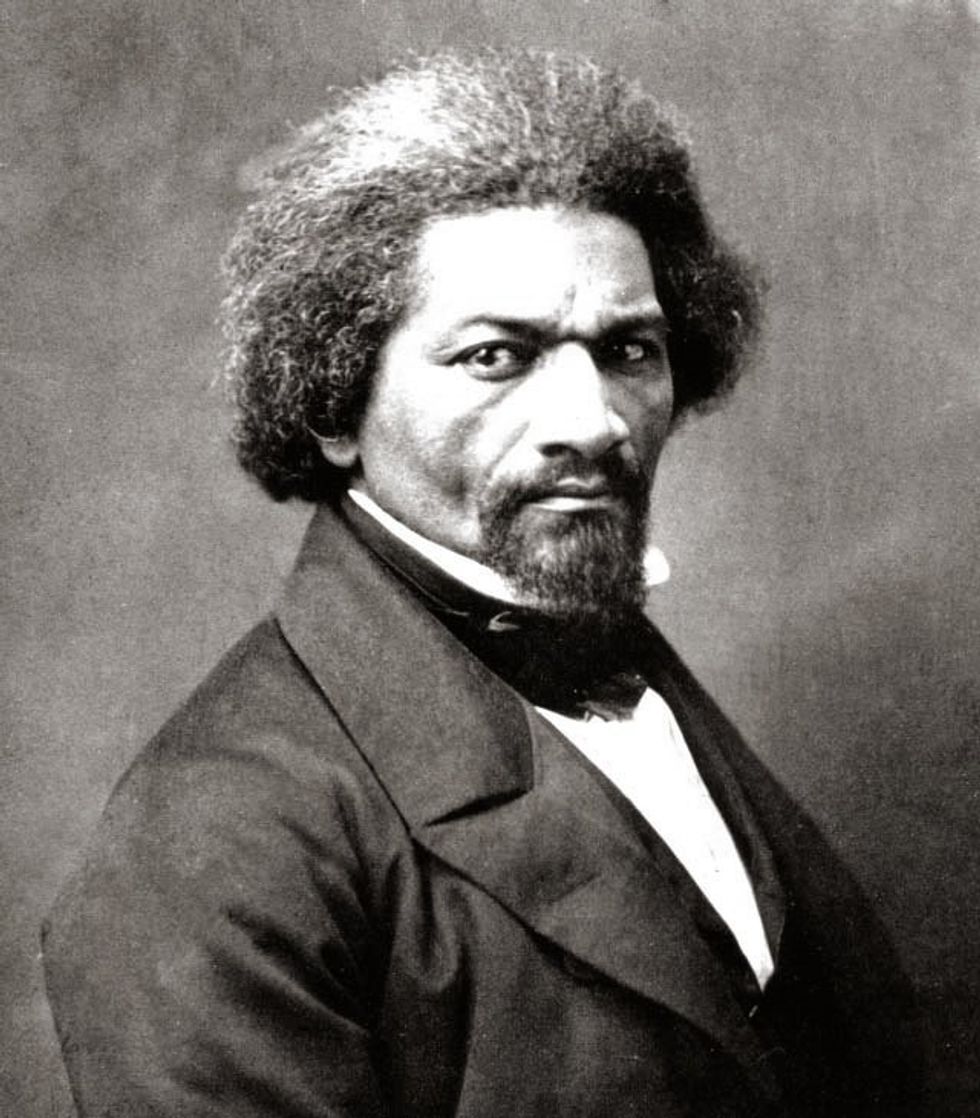

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass

Wiki Commons

Frederick Douglass, renowned abolitionist and orator, served as the United States minister resident, and consul-general to Haiti and Chargé d'affaires for Santo Domingo in 1889, appointed by President Benjamin Harrison. However, Douglass resigned in 1891, opposing President Harrison's aggressive territorial ambitions in Haiti. Haiti nonetheless honored Douglass by appointing him as a co-commissioner of its pavilion at the 1892 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. His principled stance against imperialism cost him his diplomatic career and underlines the tension Black diplomats still may feel navigating the predominantly white and upper-class U.S. Foreign Service.

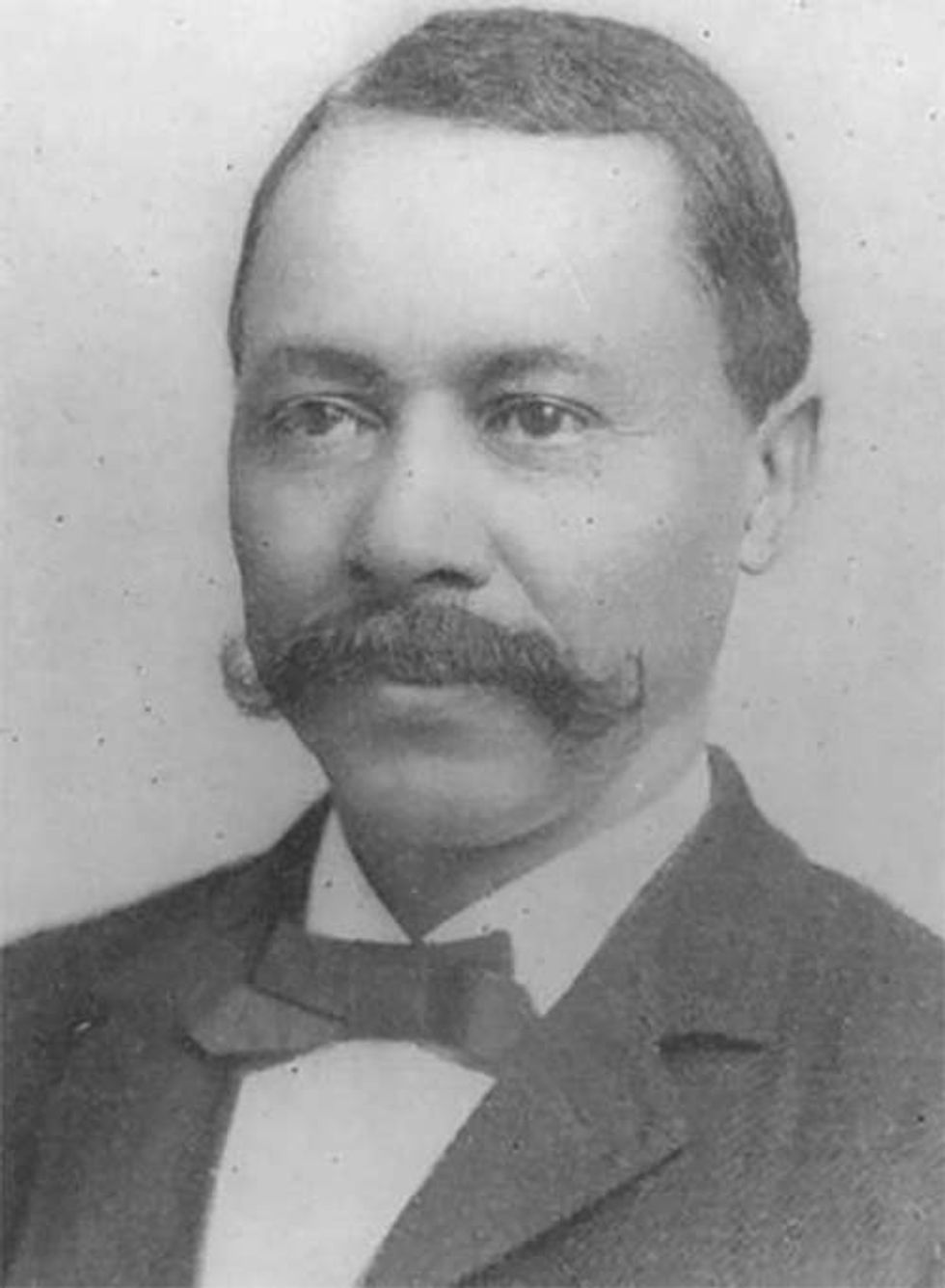

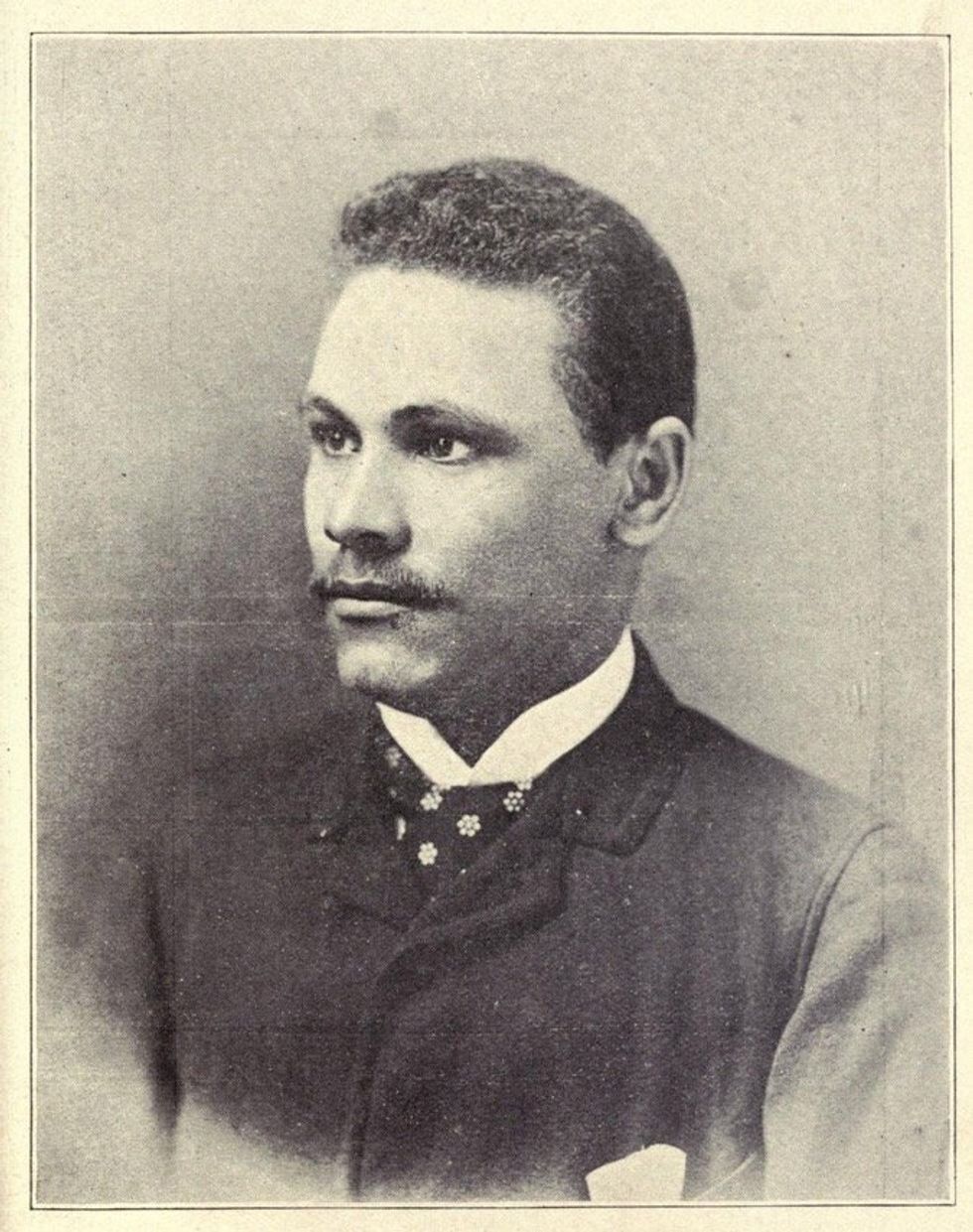

William Henry Hunt

William Henry Hunt

Wiki Commons

Hunt was born into slavery in Tennessee in 1863, the son of Sophia Hunt and the man who enslaved her. Upon emancipation, his mother took him to Nashville, where access to education allowed him to attain a post in the US Consulate in Madagascar eventually. He went on to serve in consular roles spanning from Liberia to France until his retirement on December 31, 1932, pioneering a path for Black diplomats in the 20th century.

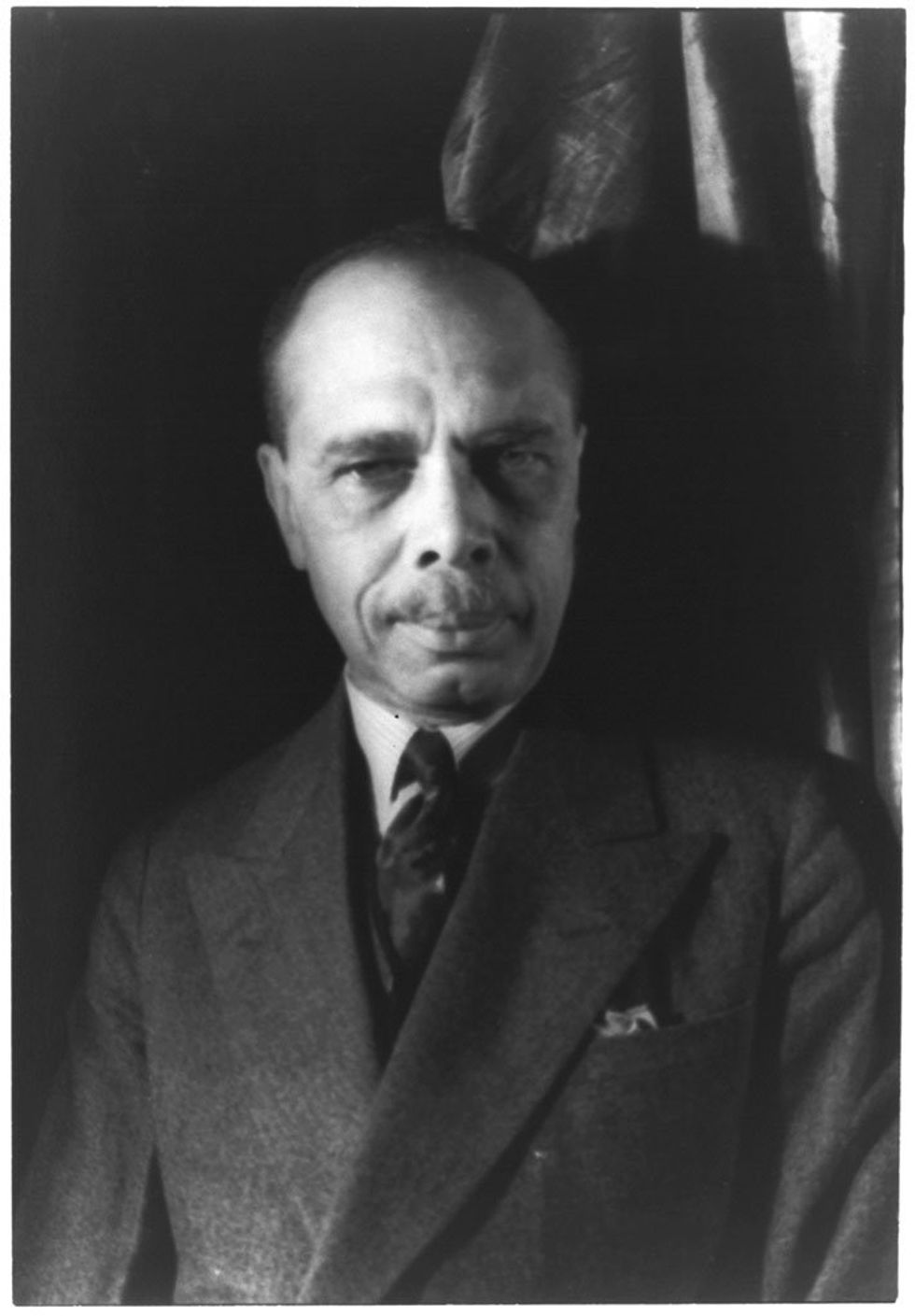

James Weldon Johnson

James Weldon Johnson

Library of Congress/Flickr Commons

Johnson served as a consul in Venezuela from 1906-1913, under President Theodore Roosevelt. However, he’s best remembered for contributions to the African-American cause that transcended diplomacy. He was a leading figure in the early days of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People – effectively its executive officer from 1920 – and wrote “The Autobiography of An Ex-Colored Man.” He also co-wrote "Lift Every Voice and Sing," often referred to as the Black National Anthem, and established the "Daily American," the first Black newspaper.

Ralph Bunche

Anefo photo collection. Dr. Ralph Bunche in Stockholm with the widow of Count Folke Bernadotte. April 10, 1949. Stockholm, Sweden.

IMAGO/piemags via Reuters Connect

Ralph Bunche was arguably the most prominent African American diplomat of the twentieth century. He worked at the State Department from 1943 to 1971, serving under every president from Franklin Roosevelt to Richard Nixon. His initial focus on civil rights for African Americans evolved into a global human rights advocacy. He played a pivotal role in the formation of the United Nations in 1945 and the adoption of the UN Declaration of Human Rights in 1948. In 1950, he won the Nobel Peace Prize for his mediation efforts in the Palestine conflict, and in 1963, President Lyndon B. Johnson awarded him a Presidential Medal of Freedom.

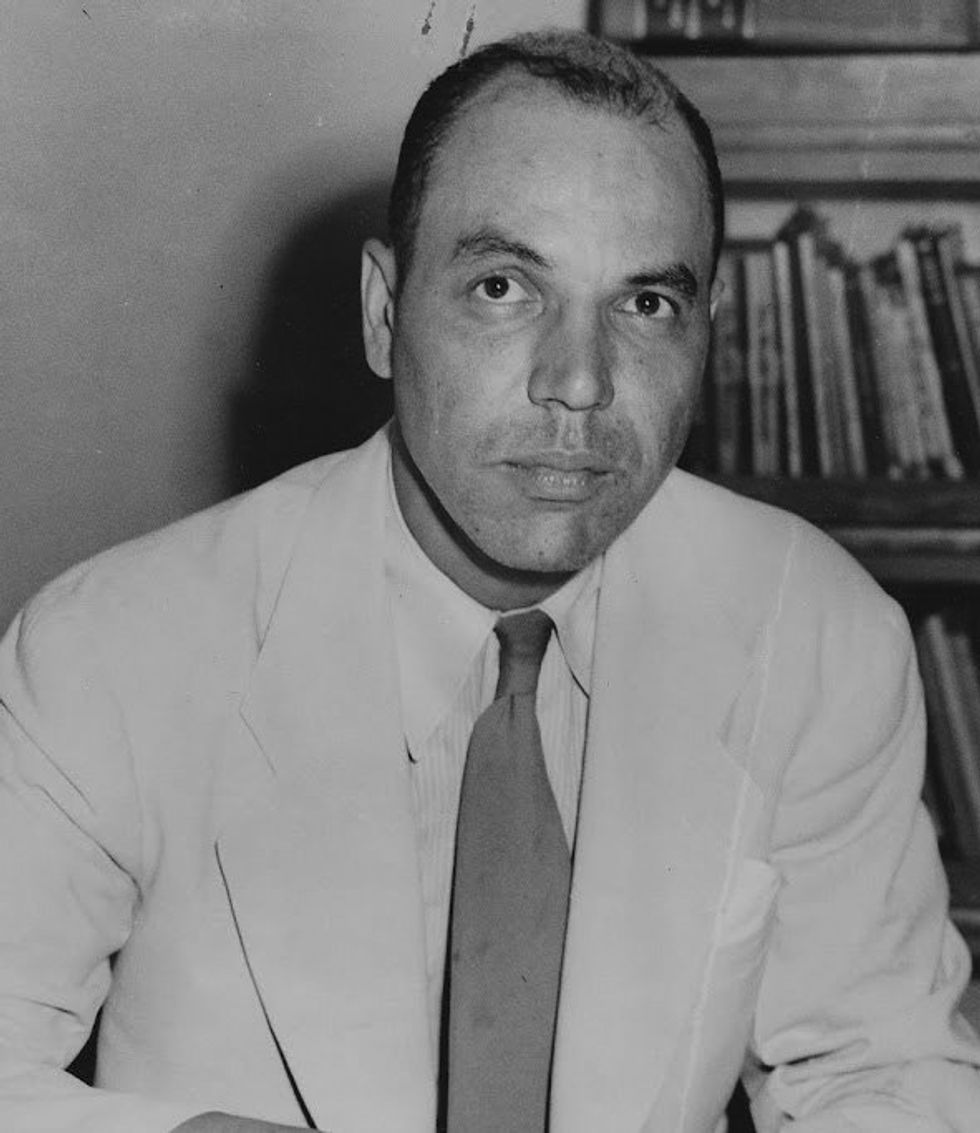

Edward Dudley

Edward Dudley

Fair Use/Flickr

Dudley was named minister to Liberia in 1948 and then an ambassador when the US raised its diplomatic mission to the embassy level the following year under the administration of Harry Truman. During this period, he and a few other Black diplomats were instrumental in the dismantling of the “Negro Circuit”, which limited the Black diplomatic corps to undesirable posts in select countries—often African and predominantly Black countries—while their white counterparts were transferred all over the world.

Clifton R Wharton Sr

Meeting with the US Ambassador to Norway Clifton R. Wharton, Sr., 3:50 PM. President John F. Kennedy sits with US Ambassador to the Kingdom of Norway, Clifton R. Wharton. Oval Office, White House, Washington, D.C.

IMAGO/piemags via Reuters Connect

Wharton was the first African American to pass the rigorous Foreign Service examination and benefitted from the advocacy against the “Negro Circuit.” He worked across embassies and consulates around the world. He was the first Black career diplomat to lead a US mission in Europe as Minister to Romania, appointed by President Dwight Eisenhower. Wharton was appointed a US representative to NATO—a first for Black Americans—and a UN delegate. USPS issued a stamp as a tribute to his impeccable service 16 years after he passed.

Carl Rowan

Meeting with the US Ambassador to Finland, Carl T. Rowan, 11:53AM. President John F. Kennedy meets with newly-appointed U.S. Ambassador to Finland, Carl T. Rowan right. West Wing Colonnade, White House, Washington, D.C.

IMAGO/piemags via Reuters Connect

Rowan rose to fame as a reporter for The Minneapolis Tribune, writing an acclaimed series about racism in America. He sat and interviewed the most prominent figures in America, including then-Senator John F. Kennedy, on the campaign trail in 1960. Impressed, Kennedy appointed Rowan Deputy Assistant Secretary of State, where he played a crucial role at the United Nations during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Later, he was the first Black director of the United States Information Agency (USIA) and, at that time, was the highest-ranking African American in the US government.

Patricia Roberts Harris

Patricia Roberts Harris

Fair Use/United States Department of Housing and Urban Development

The first African American woman to serve as a US ambassador, Harris served in Luxembourg between 1965-67 under the administration of President Lyndon Johnson. After her tenure, she was nominated as the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development in President Jimmy Carter’s cabinet in 1977. Her confirmation meant she became the first Black woman to direct a federal department.

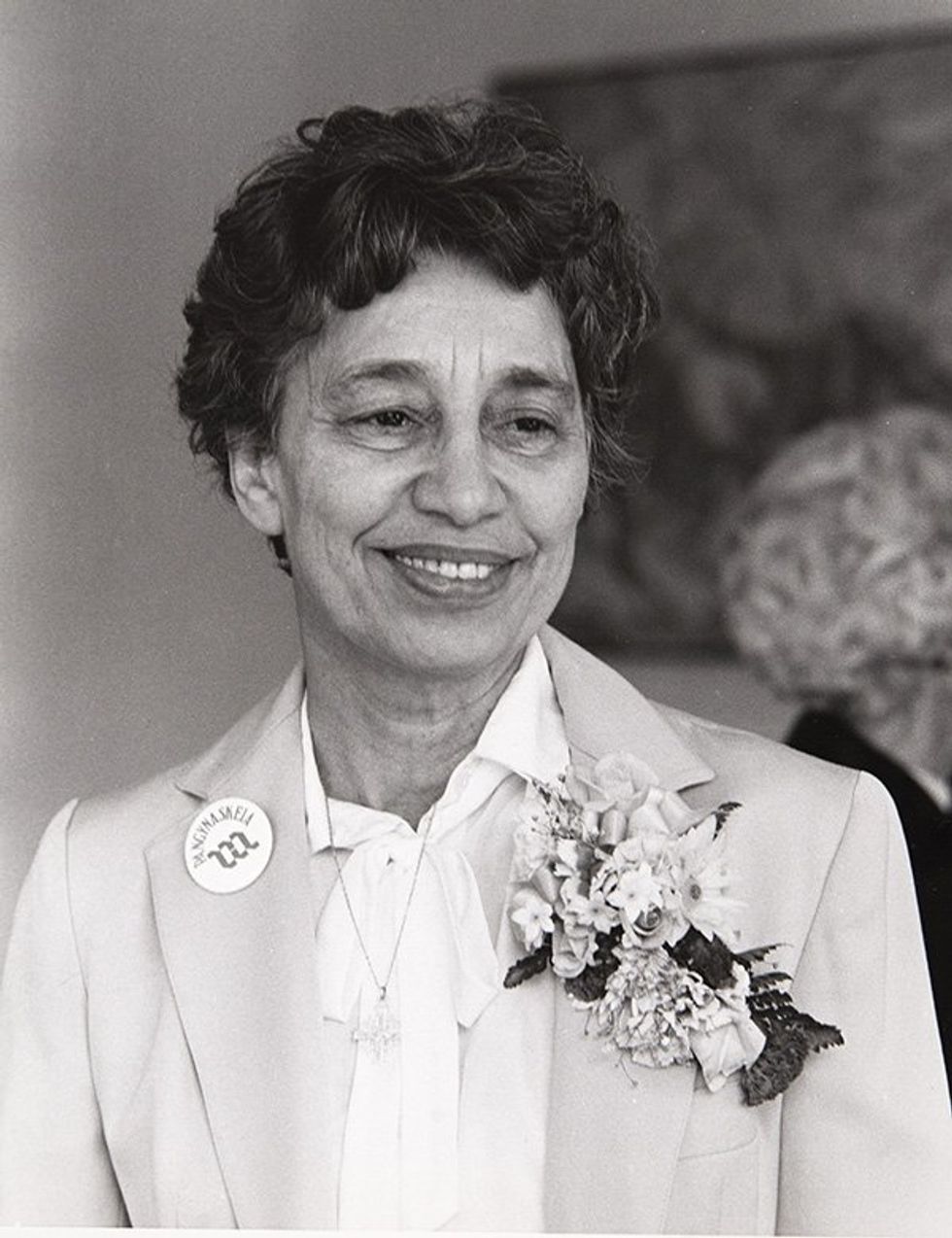

Mabel M. Smythe-Haith

Mabel M. Smythe-Haith

Fair Use/Flickr

Smythe-Haithe was the first Black woman to hold an ambassador position in Africa and the second Black female ambassador during the Carter Administration. Prior to her diplomatic career, she worked with the NAACP on the landmark Brown v. Board of Education desegregation case alongside Thurgood Marshall. She also served on the State Department’s Advisory Council for African Affairs under President John F. Kennedy.

Colin Powell

U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell makes a point as he testifies May 15, 2001, before the Senate approprations subcommittee for programs of the State Department for the fiscal year 2002.

Reuters

Born in New York to immigrant parents from Jamaica, Powell became the first Black Secretary of State under President George Bush in 2001 after a 35-year career in the military. Powell oversaw foreign policy during the worst national disaster of recent memory, the September 11 attacks. Despite accolades, his tenure was marked by controversy, notably his defense of the 2003 Iraq invasion before the United Nations Security Council. He resigned upon President Bush's 2004 reelection, but his tenure coincided with a surge in black diplomats in the Foreign Service.

Condoleezza Rice

U.S. Secretary of State-designate Condoleezza Rice sits before her U.S. Senate confirmation hearing on Capitol Hill in Washington, January 18, 2005. Rice vowed to press diplomacy in President Bush's second term after he was criticized for hawkish and unilateral policies in his first four years.

Larry Downing/Reuters

Appointed as National Security Advisor by President George W. Bush in 2002, Rice made history as the second Black person and first Black woman to serve as Secretary of State in 2005. In that role, she advocated for Israel’s withdrawal from Gaza and ceasefire negotiations with Hezbollah in 2005 – though the Bush administration’s legacy in Iraq and Afghanistan dominates memories of her tenure. Under her leadership, the State Department witnessed an increase in Black diplomats, although this progress saw setbacks under President Donald Trump.