GZERO World Clips

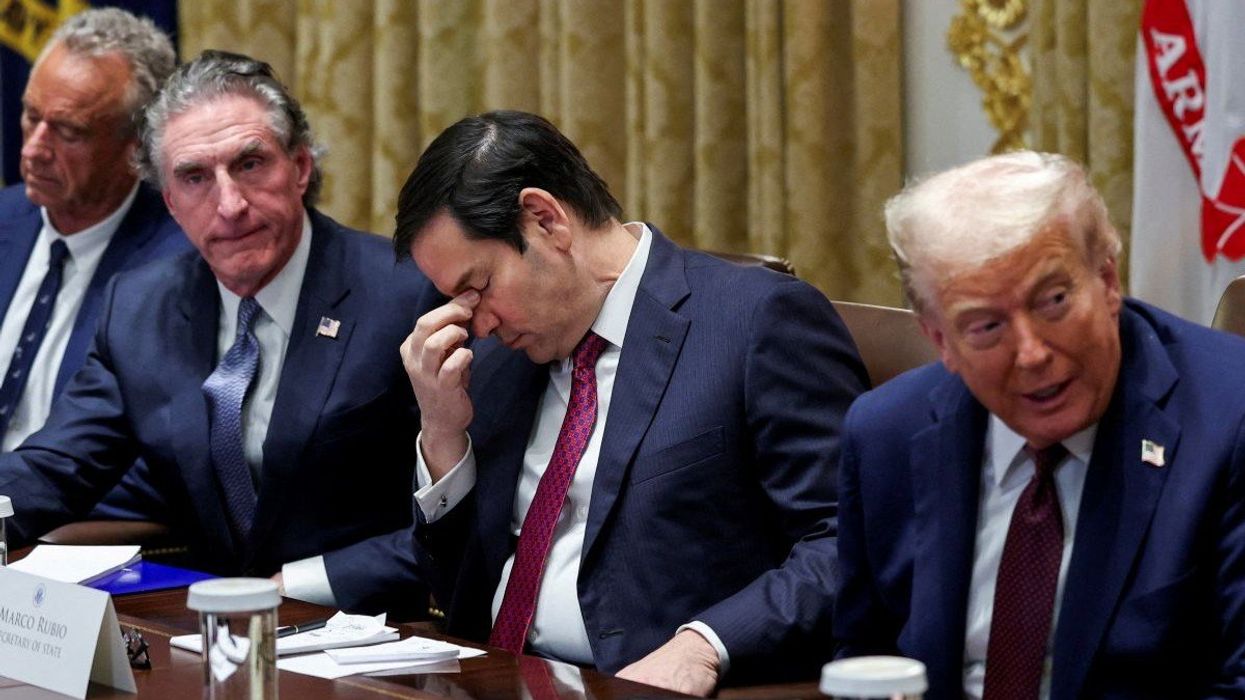

Trump's foreign policy is reshaping the world order

President Trump’s second term has rapidly reshaped global politics, with the US wielding power more aggressively, targeting weaker countries and even allies, Stephen Walt explains on GZERO World.

Jan 19, 2026