Analysis

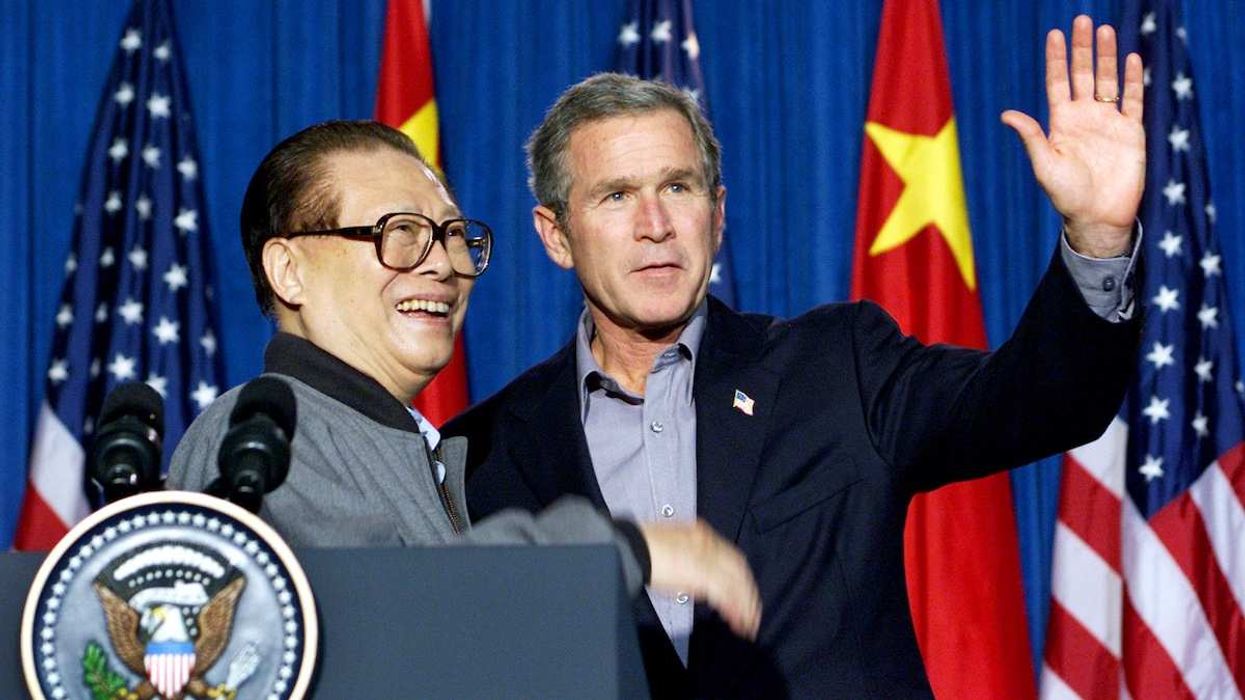

How chads and China shaped our world

At the start of the 21st century, Destiny’s Child was atop the US charts, “Google” was a little known search website with a weird name, and two things happened that would shape the world we live in today.

Dec 12, 2025