GZERO World with Ian Bremmer

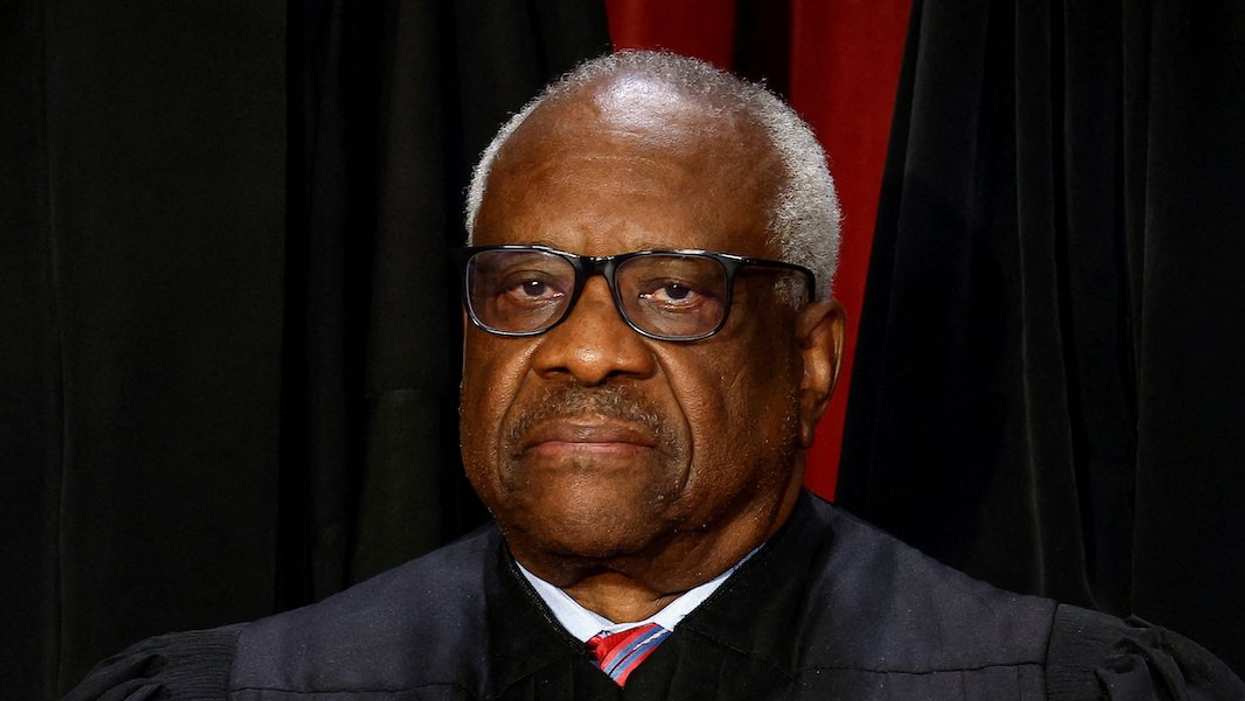

The major Supreme Court decisions to watch for in June

A look at major Supreme Court rulings expected this year, including former president Donald Trump's legal woes, abortion pills, homeless encampments, the power of federal agencies, and more, with Yale legal scholar Emily Bazelon

May 06, 2024