GZERO World Clips

Can the US stay ahead of Russia & China in the space race?

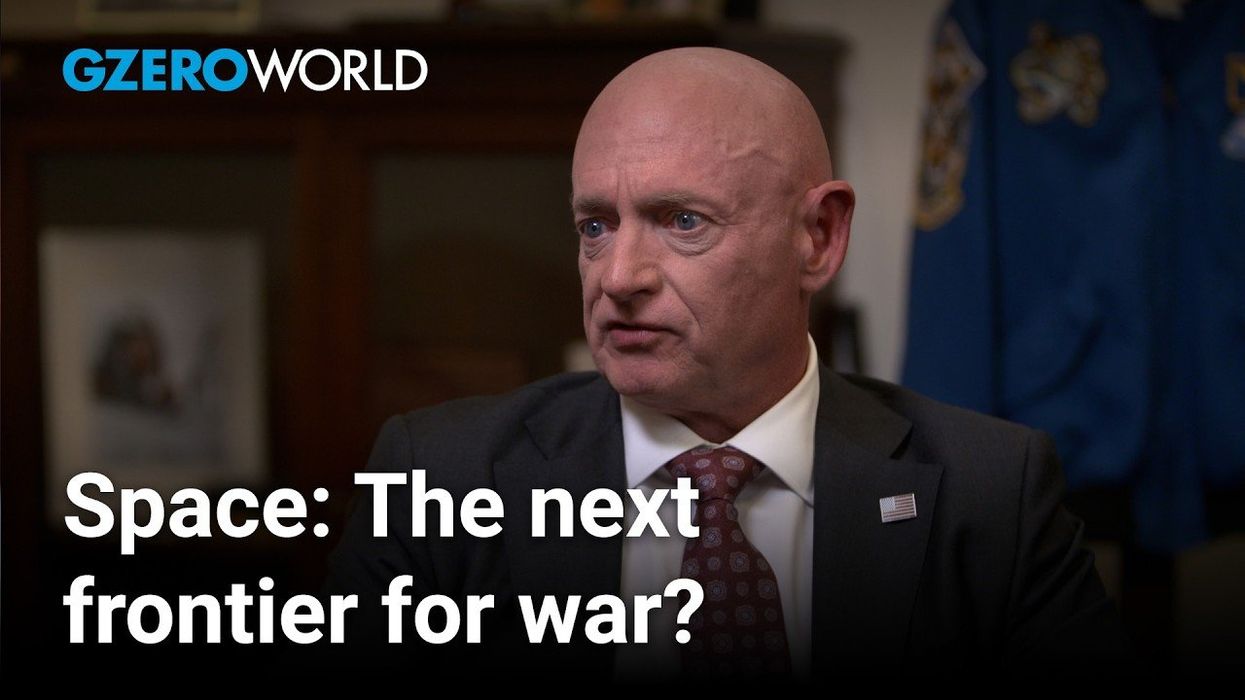

Should the United States be concerned about Chinese and Russian military activity in space? And is the US prepared for space warfare? Senator Mark Kelly (D-AZ) joined Ian Bremmer on GZERO World to talk about the future of US space policy and the 21st-century space race with Russia and China.

Sep 11, 2024