GZERO World Clips

ChatGPT and the 2024 US election

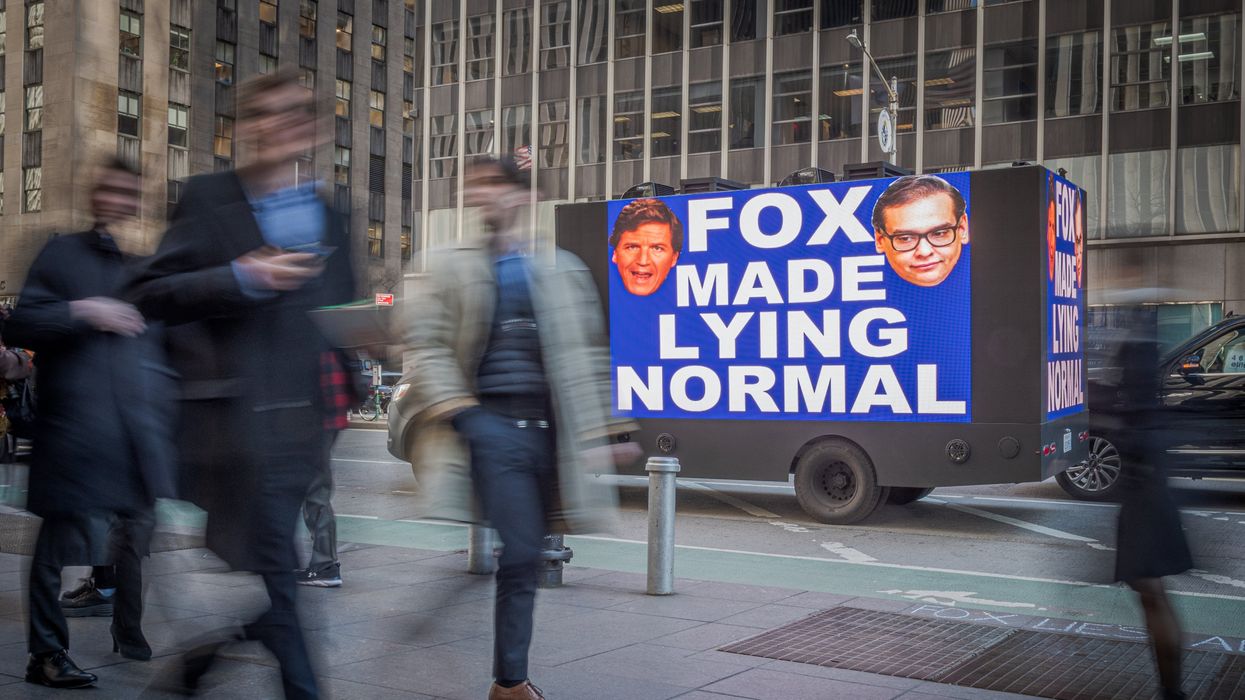

2024 will be the first US presidential election in the age of generative AI. How worried should we be about the spread of misinformation and its implications for democracy? In 2016, social media platforms became Petri dishes of disinformation as foreign actors and far-right activists spread fake stories and worked to heighten partisan divisions. The 2020 election was fraught with conspiracy theories and baseless claims about voter fraud.

Jul 27, 2023