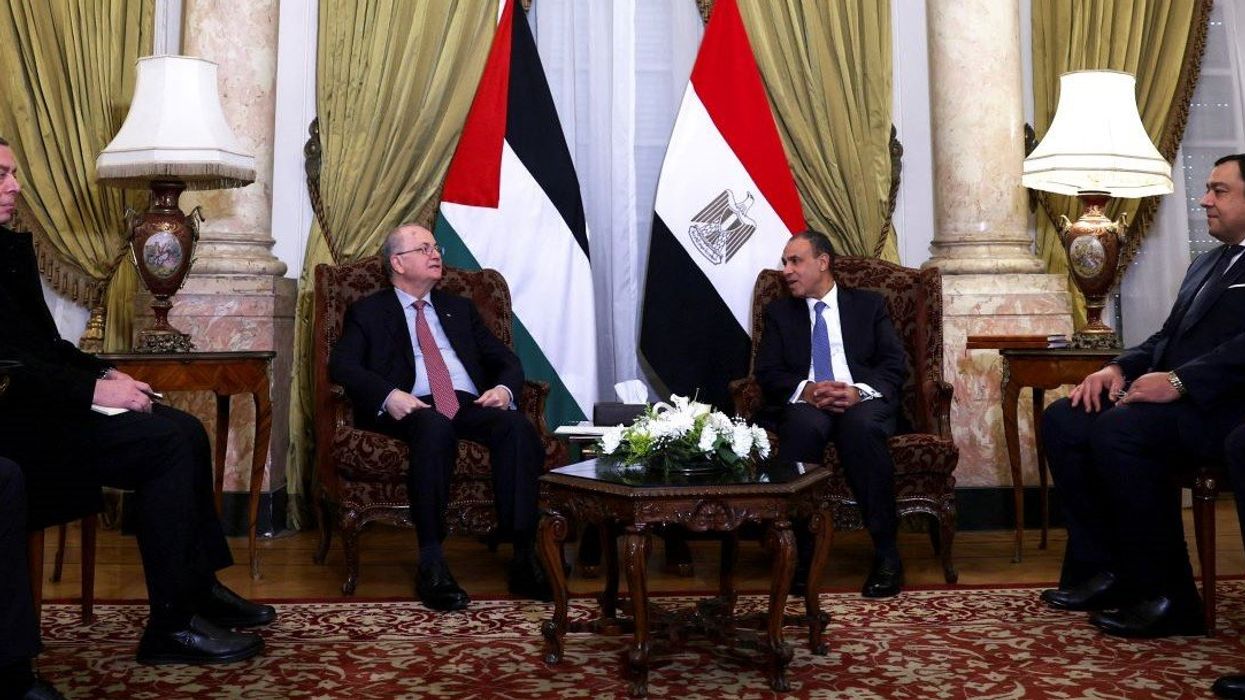

Analysis

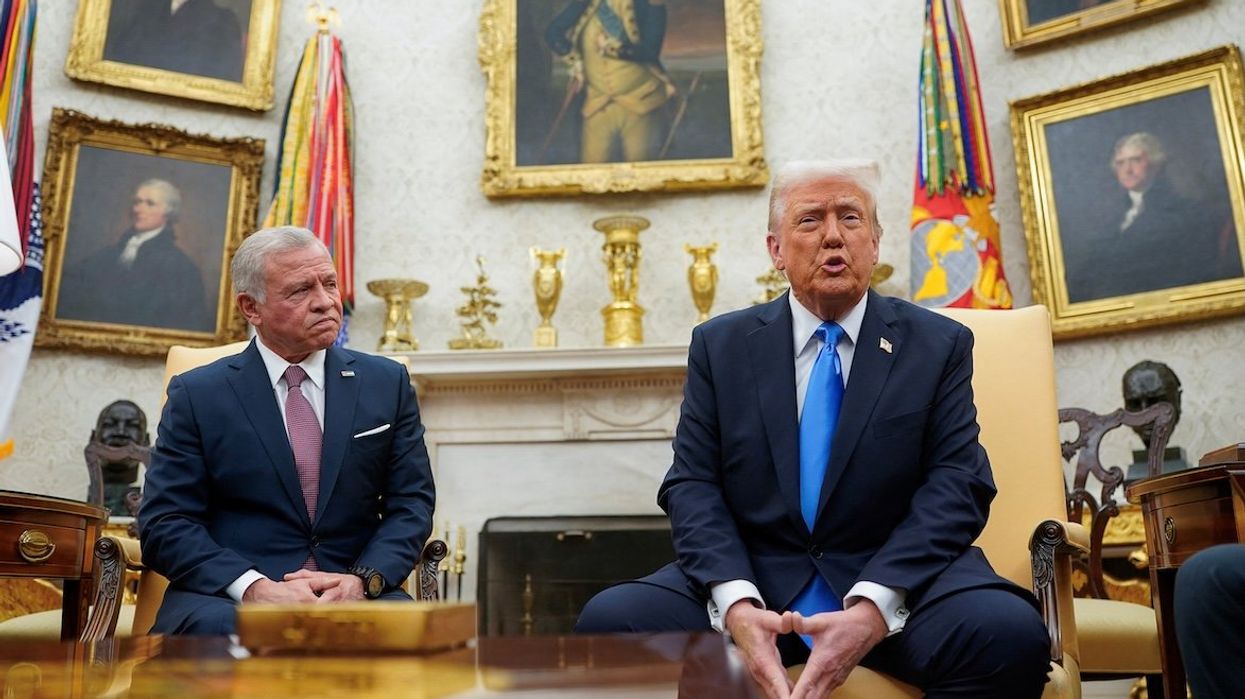

Egypt’s Undemocratic Election - And Why the West doesn’t care

Egyptians are voting this month in parliamentary elections that aren’t expected to change who’s in charge, but could allow President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi to rule beyond 2030.

Dec 08, 2025