by ian bremmer

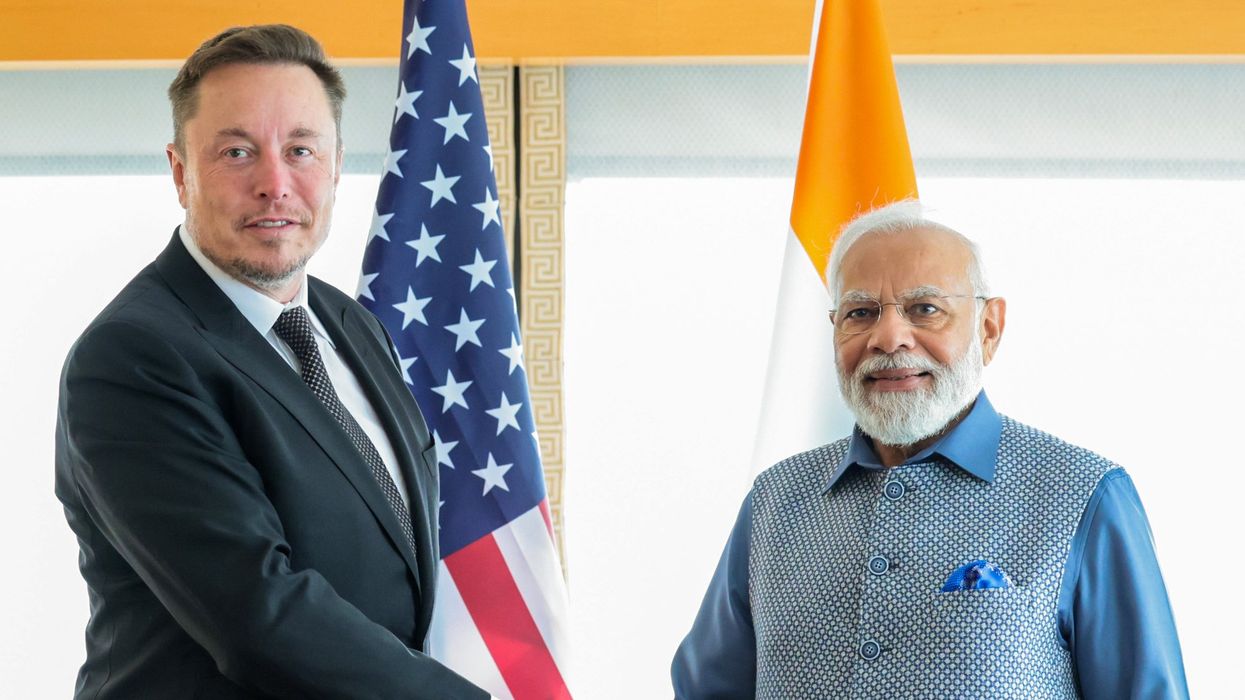

Why governments vs. Big Tech is the wrong question

It’s been three and a half years since I first laid out the idea of a technopolar world: one no longer dominated solely by states, but increasingly shaped – and sometimes steered – by a handful of powerful tech companies with the newfound ability to influence economies, societies, politics, and geopolitics.

May 14, 2025