GZERO North

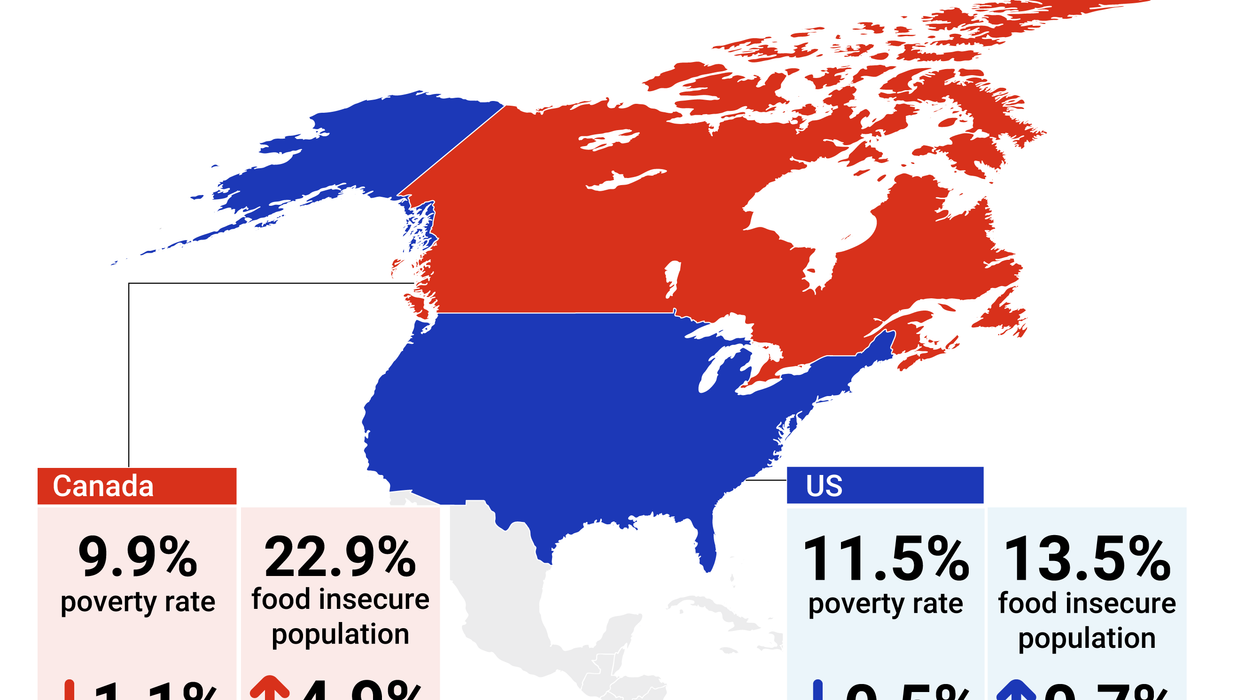

Graphic Truth: Food insecurity spikes

Hunger and poverty are on the rise in both the United States and Canada, with food insecurity levels spiking dramatically in 2023 as COVID-19 assistance programs expired. That’s been compounded by rising food costs that have left millions struggling to put food on the table.

Mar 27, 2025