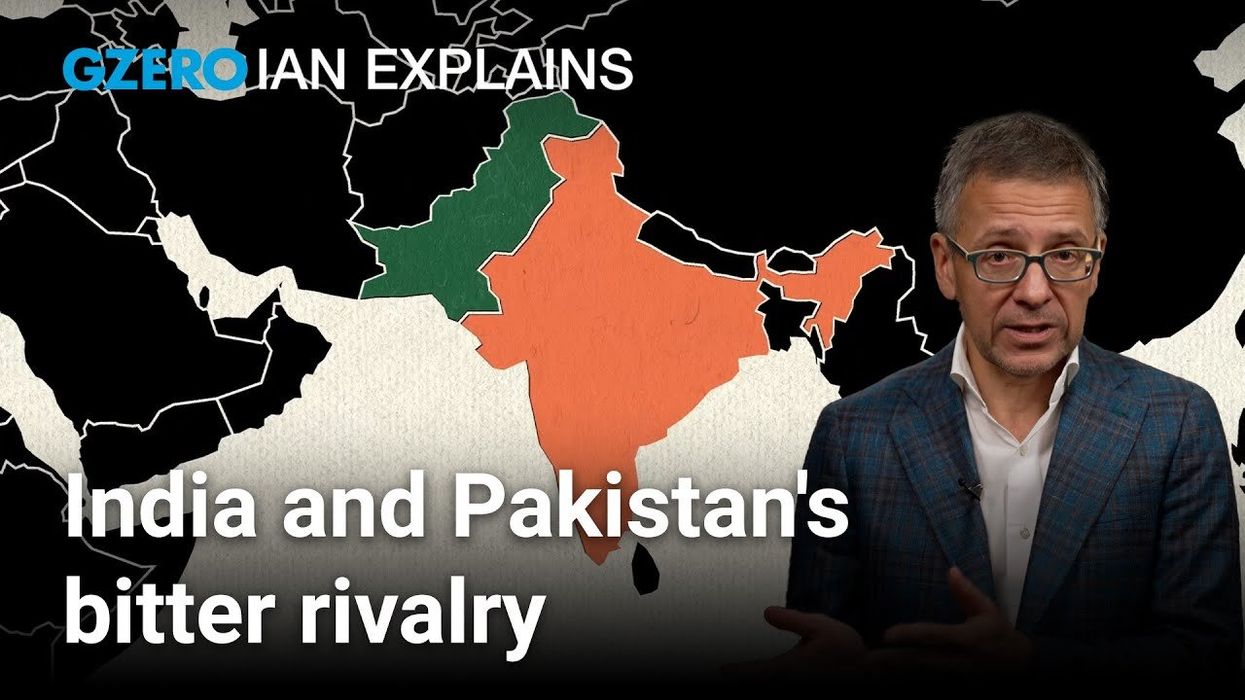

Ian Explains

Why India and Pakistan can't get along

A military confrontation between India and Pakistan in May nearly pushed the two nuclear-armed countries to the brink of war. On Ian Explains, Ian Bremmer breaks down the complicated history of the India-Pakistan conflict, one of the most contentious and bitter rivalries in the world.

Aug 15, 2025